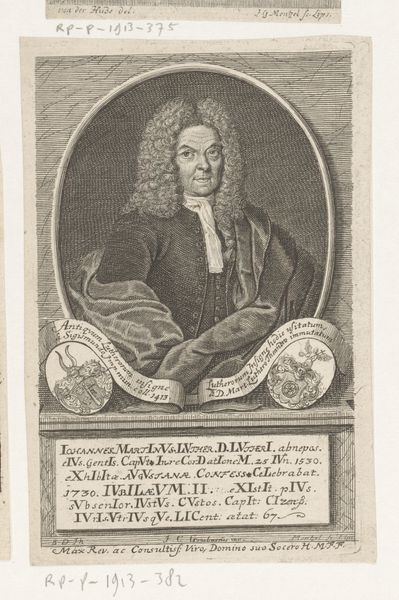

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 95 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this, I immediately get a sense of restrained formality. It's almost severe, wouldn't you say? Editor: This is indeed a fascinating image. What we have here is an engraving, dating from the period of 1727 to 1755. The work, known as "Portret van Johann Michael Weinreich", was created by Tobias Gabriel Beck. These types of prints often served not just as representations but as assertions of status within specific societal frameworks. Curator: The collar is striking, definitely signifying status as well as the somber expression... But beyond its value as a period piece, what narrative does this portrait invite? Who exactly was Johann Michael Weinreich within his context, and whose perspectives does this portrait silence? Editor: Weinreich, as identified within the portrait itself, was a Hoff-Diaconus, a deacon affiliated with the court. Given that this engraving would have circulated within specific social circles, understanding those circles is crucial. Who commissioned it? For what purpose? These are key considerations when looking at such historical objects. Consider that this was probably distributed in books, perhaps a dedication page, solidifying a cultural link. Curator: Absolutely. I agree. It brings up an interesting dynamic of power: the printing and distribution would reinforce existing class divisions as much as display individual merit. Is there an element of cultural capital operating within this representation? This is worth asking as much as it matters whether Beck even tried to engage his subject or simply reproduced his role. Editor: Certainly, the performative aspect of portraits in this era can’t be overlooked. We have Beck here actively participating, not merely reflecting Weinreich. And so much detail put into an object intended for much more restricted viewing compared to today! Now the very existence of this work raises discussions regarding art and cultural preservation that are part of much larger socio-political currents. Curator: True! Seeing these kinds of early prints brings new questions for the current era of mass reproducibility of imagery, wouldn’t you agree? We begin to examine how, even in seemingly straightforward representational engravings, complex dynamics are happening around identity, class, and the politics of image-making. Editor: Indeed. This engraving is a starting point for numerous discussions – about art as social history, the evolution of portraiture, and even how we understand notions of the individual and representation in an age of visual saturation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.