![Single-Line Calligraphy [center of a triptych of single-line calligraphies] by Gaoquan Xingdun](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2I0OTUyOGYyLWU3ZWUtNGYzYy04OTZlLThhZTdlYjU5N2NhMS9iNDk1MjhmMi1lN2VlLTRmM2MtODk2ZS04YWU3ZWI1OTdjYTFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

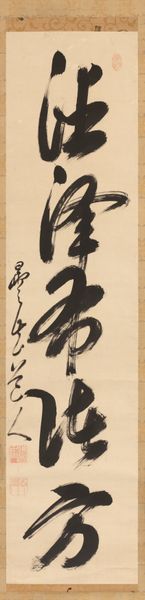

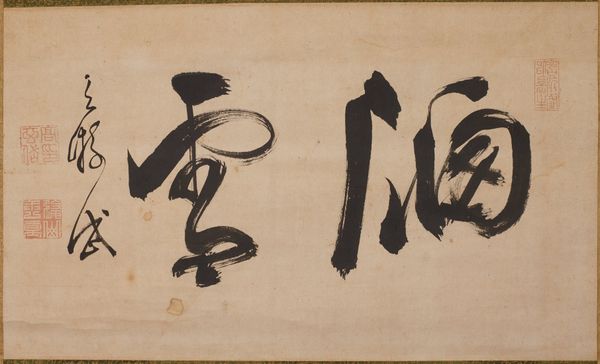

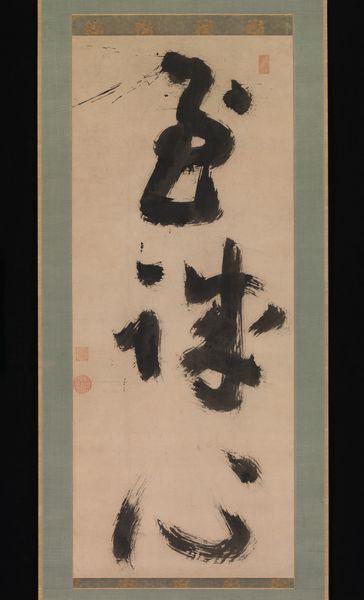

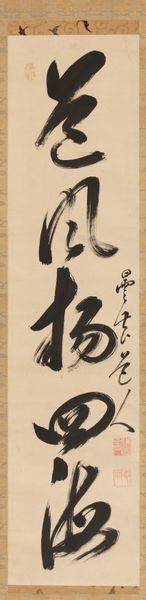

Single-Line Calligraphy [center of a triptych of single-line calligraphies] 1690

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink-on-paper, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

paper

#

ink-on-paper

#

ink

#

abstraction

#

line

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 52 1/4 × 12 1/2 in. (132.72 × 31.75 cm) (image)87 1/2 × 16 3/4 in. (222.25 × 42.55 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

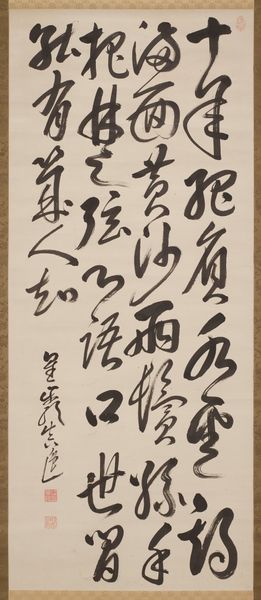

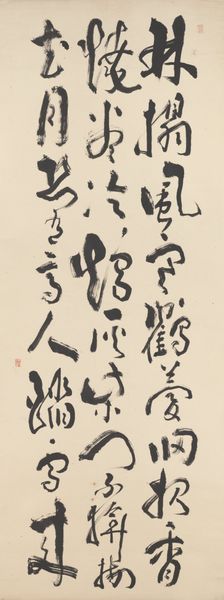

This calligraphic scroll was made in China in the 17th century by Gaoquan Xingdun, using ink on paper. Look closely, and you’ll notice that this is not simply writing, but a performance. The artist has swept the brush across the absorbent surface to create bold and fluid characters, which expand and contract, pushing the ink to its limit. The density of the ink is critical. Too thin, and the strokes would be weak. Too thick, and the brush would drag. Consider also the paper itself. Its absorbency allows the ink to bloom, creating soft edges and a sense of depth. Calligraphy like this also relies on a whole ecosystem of production. Highly skilled papermakers, brushmakers, and ink producers all contribute to the finished work. Yet, in the end, it is the calligrapher's skill that brings all of these elements together. The work embodies a sophisticated understanding of materials and process, elevating craft to the level of high art.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

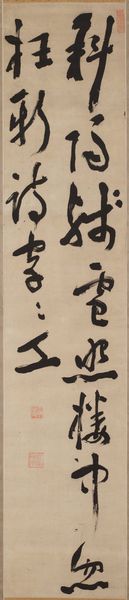

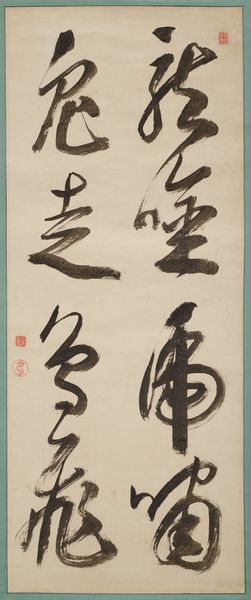

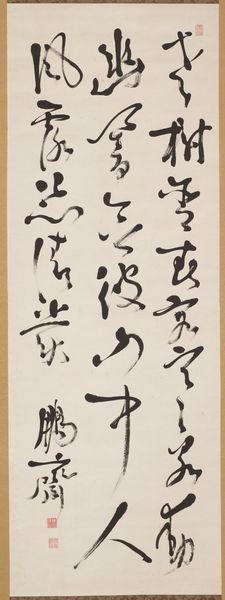

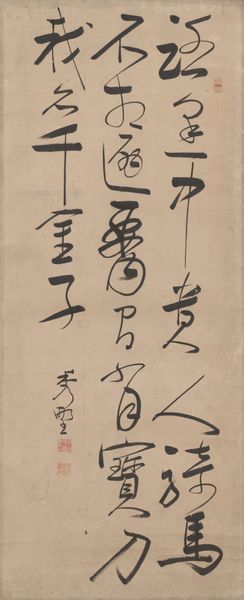

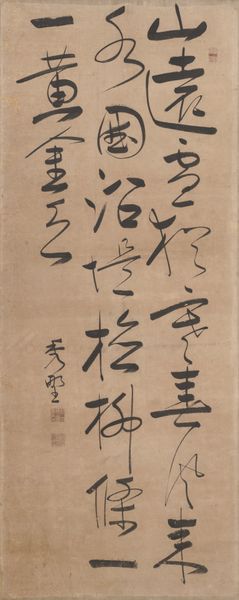

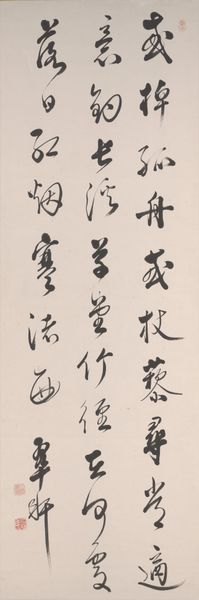

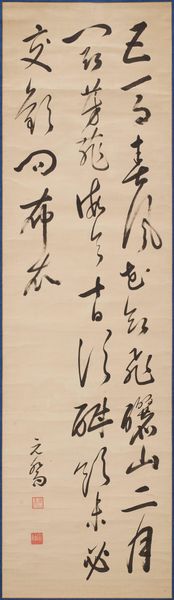

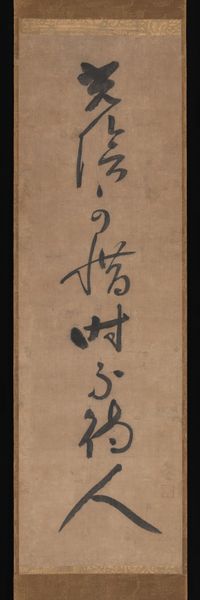

The written word is of utmost importance in Japanese Zen. Handwritten texts by Zen teachers—everything from lectures and certificates to poems and personal correspondence—are treasured as bokuseki, “ink traces” of the master, and displayed in monasteries for their didactic potential as well as for the beauty of the writing itself. This triptych of scrolls features the bold, semi-cursive calligraphy of Gaoquan Xingdun, a Chinese monk who immigrated to Japan in 1661 and became a central figure in the early development of the O_baku school, or sect, of Zen. Each scroll includes a single, five-character Zen maxim: “Eternal blessings on the wise ruler” on the important central scroll; “Religious spirit spreads across the four seas” at right; and “Beneficent graces permeate the world” at left.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.