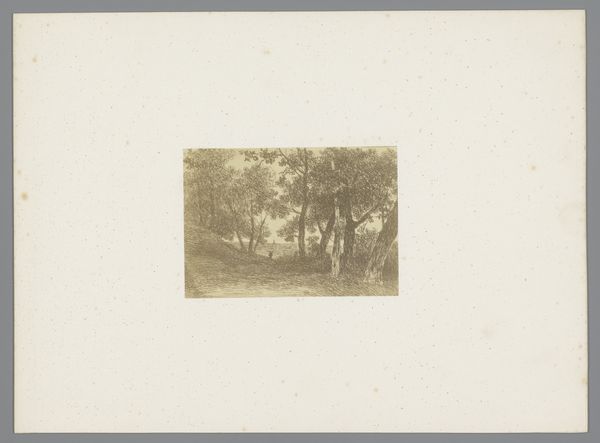

photography

#

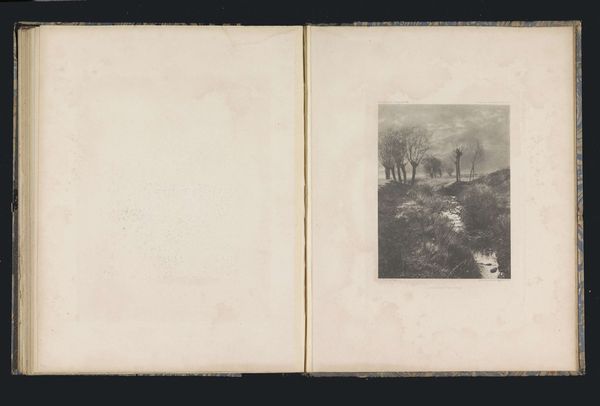

landscape

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 177 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This striking landscape photograph, "View of Ulvik on the Hardangerfjord, Norway" by Knud Knudsen, dates between 1861 and 1870. What strikes me most is how it captures both the vastness of the scenery and an intimate sense of place. What’s your take? Curator: It's interesting how early landscape photography like this contributed to the construction of national identity. The Hardangerfjord would have been seen as embodying the rugged, untamed spirit of Norway. But think about how this image circulated. Who was seeing it, and what did it mean for them? Editor: So it wasn't just about documenting a place, but also about shaping a national image. It makes you wonder who had access to such imagery then. Was it mostly consumed by wealthy urban elites or distributed more widely? Curator: Exactly! Photography, though a relatively new technology, was already caught up in questions of representation and power. How does seeing Norway framed in this way impact its place in the world stage? These photos helped forge a specific visual identity for Norway and influenced how it was perceived by outsiders, perhaps encouraging tourism or investment. Notice, too, the very act of framing this particular vista leaves out so much. Editor: It’s fascinating how something seemingly objective like a photograph can be so heavily laden with social and political implications. The composition, carefully chosen, can reinforce pre-existing notions of what is valuable or representative of a place. Curator: Precisely. Early landscape photography often served to legitimize territorial claims and fuel national narratives. We must remember that the "realism" it presents is always a constructed one, and it is part of larger conversations regarding representation and the role of visual culture. Editor: I’ll definitely be approaching landscape photography with a more critical eye from now on! It's more than just pretty pictures. Curator: Indeed. It’s about understanding how images actively participate in the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.