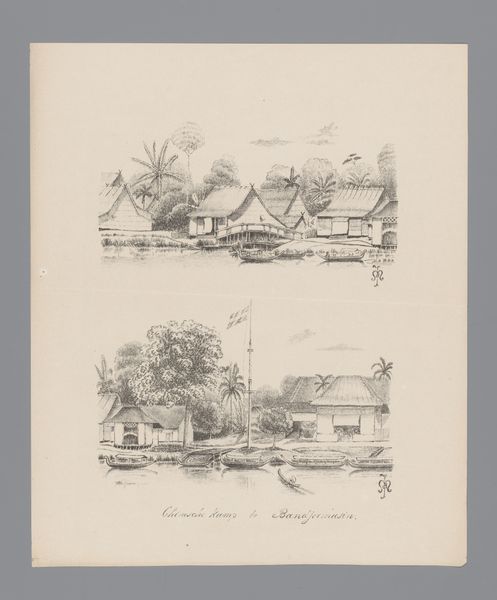

Koninklijk stoomschip Madura in 1866 en Fort Tatas te Bandjermasin after 1838

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 385 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

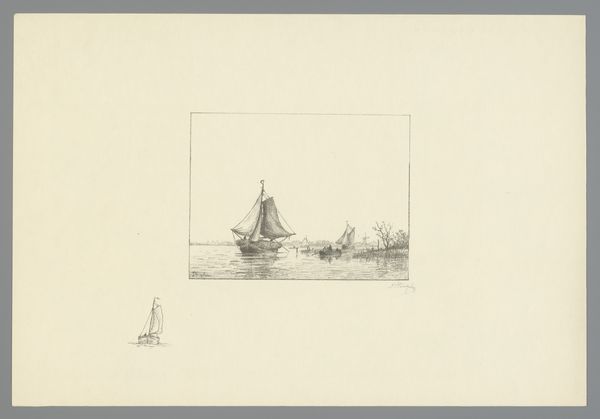

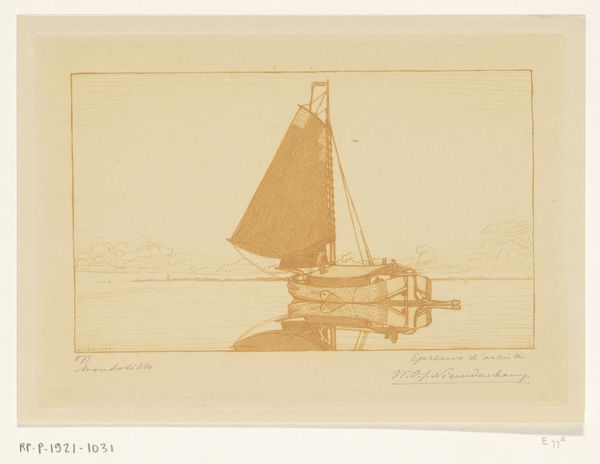

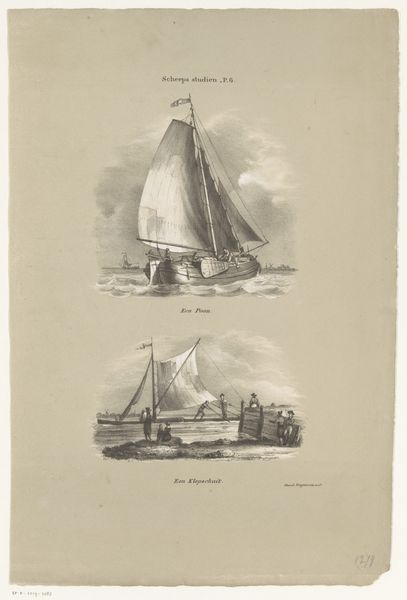

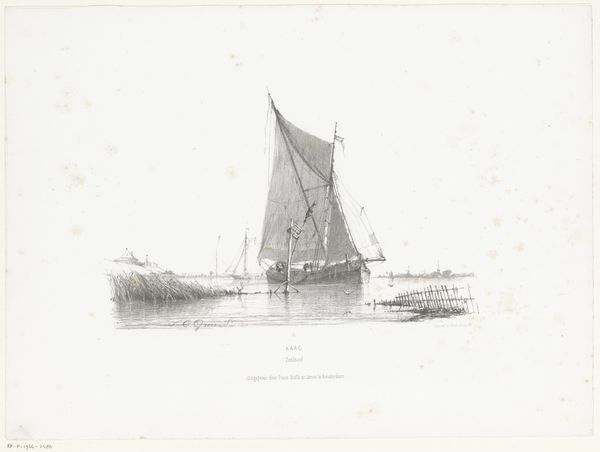

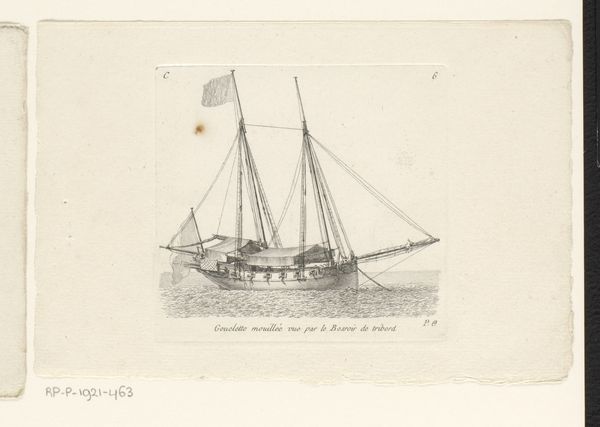

Curator: Today, we are examining Willem Mathol de Jong's drawing, "Koninklijk stoomschip Madura in 1866 en Fort Tatas te Bandjermasin," created sometime after 1838. It’s rendered in ink on paper, depicting a cityscape in what was then known as the Dutch East Indies. Editor: Immediately striking! The contrast achieved through delicate strokes evokes a sense of tranquility, yet the composition, split into the ship above and fort below, hints at underlying tension. Curator: Indeed. The composition reflects the duality of colonial presence. The steamship, a symbol of Dutch industrial power and trade, sits above the fort, representing military and administrative control over Bandjermasin. Editor: Observe how the artist used line weight to give depth to the steamship. The subtle shading around the hull makes it appear almost buoyant. What strikes you most about the textures achieved? Curator: Well, to me it's the historical context that adds depth. The Dutch presence in Bandjermasin was marked by conflict and exploitation, so this seemingly peaceful image becomes charged when considering the power dynamics at play in 1866. The Madura would have facilitated resource extraction and troop movement. Editor: Ah, yes! We see two separate sketches in the same visual plane. What did de Jong intend by representing both, in this particular order? Curator: De Jong, as an academic artist trained in European styles, would have been capturing what was, to the Dutch, an exotic landscape. It’s Orientalism manifested as reportage, softening the harsh realities of colonial administration through idealized imagery intended for consumption back in Europe. Editor: Ultimately, it becomes a dance between what’s visible and what’s unspoken. De Jong may have believed his art innocent; we cannot believe that about the colonial context that supported its creation. Curator: Precisely! Examining images like this compels us to consider both their aesthetic qualities and the complex histories they embody. Editor: Agreed. An intricate play of light and shadow. It seems the formal elements offer much on their own. The knowledge surrounding them only makes it richer.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.