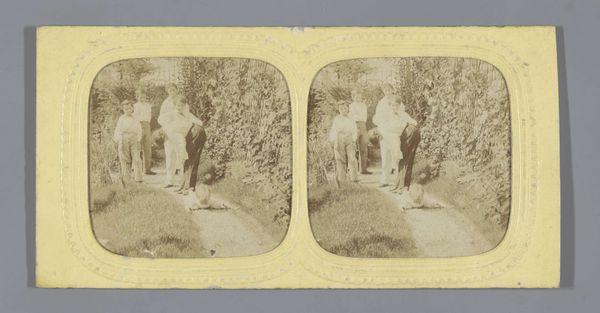

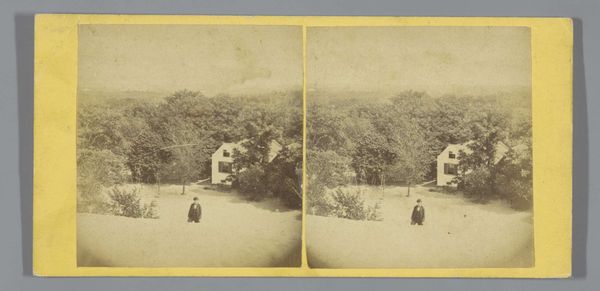

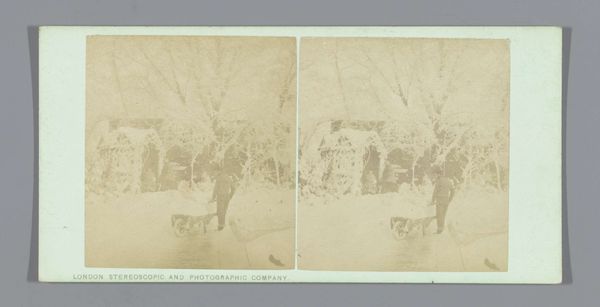

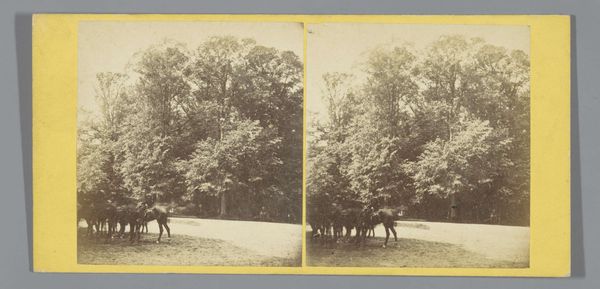

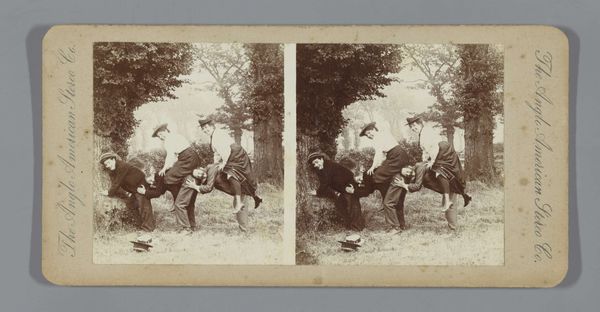

Geitenkar van Napoleon Eugène Lodewijk Bonaparte in de tuin van het Kasteel van Saint-Cloud c. 1858 - 1865

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right now we're looking at an albumen print made sometime between 1858 and 1865 by Furne Fils and H. Tournier. The title translates to "Goat Cart of Napoleon Eugène Louis Bonaparte in the Garden of the Castle of Saint-Cloud". Editor: The sepia tones really evoke a lost world, don’t they? It's more than just a document; it’s as if a memory is breathing right here in front of us, slightly faded, softened. The light itself feels nostalgic, almost melancholic, like a warm day turning toward dusk. Curator: Well, the albumen print process would definitely contribute to that impression. It was one of the first commercially viable methods for producing photographic prints on paper, using egg whites to bind the image to the paper. It gives a distinctive sheen and tonal range. What’s interesting to me is the deliberate construction of the scene. This wasn't just a snapshot. Editor: Exactly. It's posed, meticulously staged. The little prince in his miniature goat-drawn carriage, the carefully positioned greenery in the background... It's about projecting an image, a narrative. There's an almost theatrical quality to it, like a still from a play about idyllic childhood and imperial leisure. And, perhaps, it's more propaganda than portraiture. Curator: Precisely. These early photographs served very specific functions within the social and political context. Disseminating images of the imperial family engaged in wholesome, pastoral activities reinforced their connection to the nation, portraying an image of stability and tradition. The choice of materials, too—the photographic paper itself, the way it was circulated as a stereograph—speaks to a deliberate effort to reach a broad audience. Editor: I can almost feel the smooth, cool texture of the print. The subtle imperfections, like those little specks in the sky. These imperfections aren’t flaws, they’re proof of the handmade nature of the piece, little whispers telling us where the technology meets humanity, the mechanical meeting the tender human touch. Curator: Absolutely. Seeing the wear and tear, these small artifacts of age, connects us to the history of this object itself, its travels through time, the hands that held it. Editor: For me, beyond the social implications, the art speaks of a delicate human need: the desire for permanence in the face of impermanence, a longing captured in amber light and subtle fading. Curator: For me it highlights the crucial role photography played in shaping public perception and bolstering the Bonapartist regime. Different interpretations coexisting quite harmoniously.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.