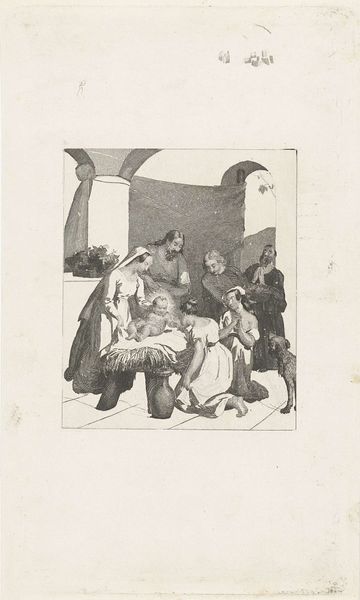

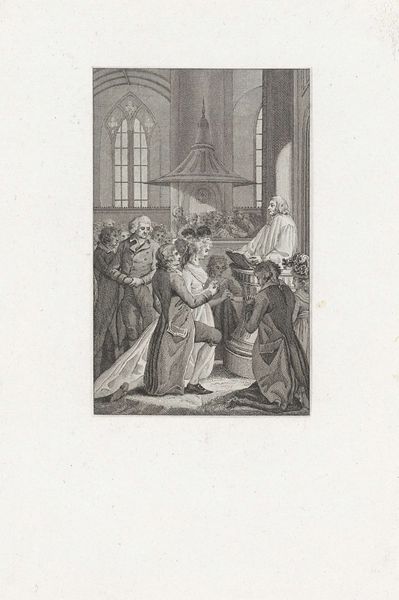

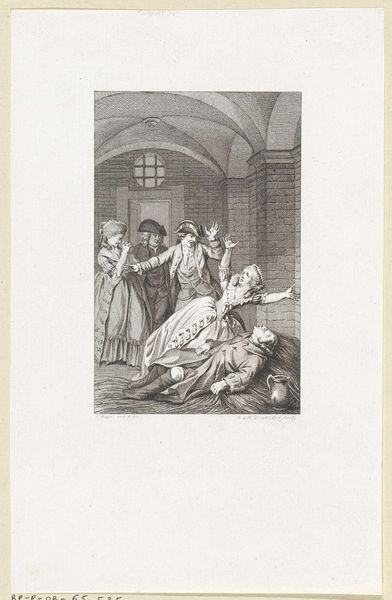

Eleonora van Engeland met haar twee zoons voor haar man graaf Reinoud II c. 1853

0:00

0:00

drawing, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

mother

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

pencil

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jacobus van Dijck's drawing from around 1853, "Eleonora van Engeland met haar twee zoons voor haar man graaf Reinoud II," using ink and pencil. There's a striking formality and subdued emotion here, even in the embrace of the figures. How would you interpret its place in the artistic and historical landscape? Curator: This work is deeply entrenched in the historicism of the 19th century. The medieval style is very evocative and immediately places demands on how the public might have viewed the imagery: we see how this reflects a wider fascination with an idealised version of the medieval past. What's particularly interesting is how artists like Van Dijck deployed these historical references to convey contemporary social or political messages. Do you think this scene of supposed reconciliation carries any of that weight? Editor: I can see the staging of power dynamics, for sure. Is this perhaps connected with how the Netherlands was constructing its national identity at this time? Curator: Precisely! History paintings and drawings like this were frequently commissioned or created to build a sense of national pride, solidifying historical narratives that legitimised existing power structures. The choice of subject matter and the way it is portrayed serves to reinforce those narratives. Do you see the echoes of religious painting in the arrangement of the figures? Editor: Now that you mention it, definitely, especially the positioning of the figures on different levels. Curator: That compositional technique also communicates hierarchies. Thinking about the public reception of such a piece, consider where and how it would have been displayed. In a museum, a gallery, or perhaps as a print circulated amongst the populace? The context of display is crucial to understanding the work’s impact. Editor: I hadn't considered the distribution method impacting meaning, but that makes so much sense. I am now pondering how popular imagery helps build popular perception of the national identity. Curator: It’s a dialogue between artist, patron, subject and, most importantly, the audience, influencing how history itself is remembered and retold.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.