photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life-photography

#

toned paper

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

united-states

Dimensions: 8 × 8.3 cm (each image); 8.7 × 17.6 cm (card)

Copyright: Public Domain

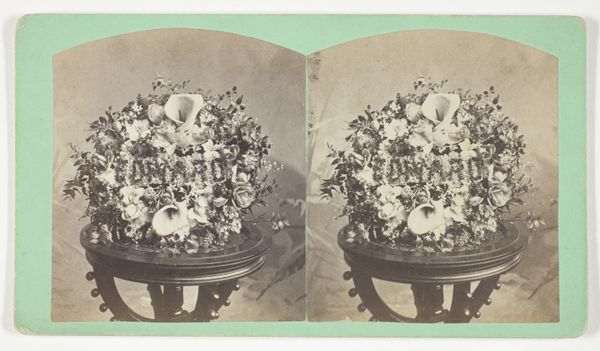

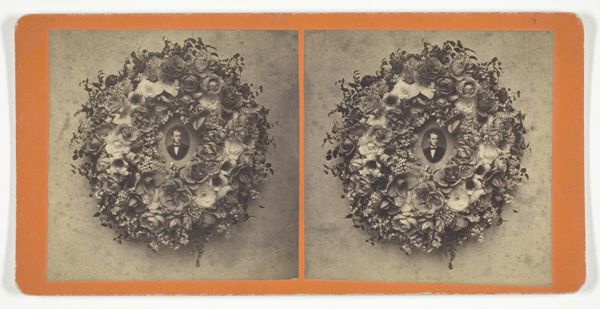

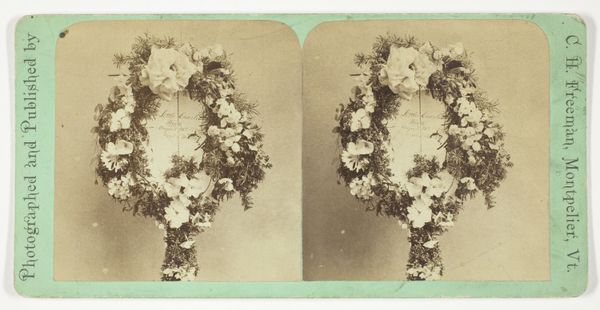

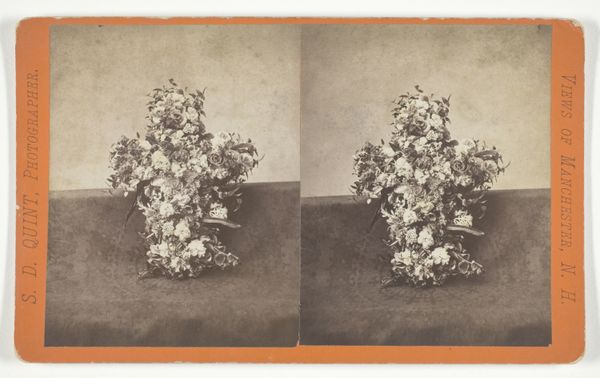

Curator: Well, this is certainly... interesting. Is it just me, or does anyone else get a very somber, almost morbid feeling from it? The sheer number of flowers arranged, those wreaths...it's a lot to take in. Editor: It is evocative. What you’re seeing is a gelatin silver print on toned paper. It's simply titled "Untitled," and it was created somewhere between 1875 and 1899. Its origins trace back to the United States. This particular piece is held here at The Art Institute of Chicago. It resonates powerfully within conversations concerning rituals around death, memory, and representation in late 19th-century America. Curator: A lot of florals. Clearly they are staged on what looks like a table draped with a dark fabric. And those arrangements are quite symbolic – I see what looks like a wreath shaped like an anchor? And is that a pair of linked rings? It suggests marriage… or remembrance after death, perhaps? It feels incredibly formal, even performative. Editor: That anchor you’ve identified connects deeply with symbols of hope, steadfastness, and even salvation within mourning traditions. Those rings underscore themes of eternal love. Taken as a whole, there is a clear narrative—love, loss, and a certain memorial theatre of grief that defined an era. What interests me most is how death became increasingly commercialized and ritualized during that period, which this still-life captures beautifully. Curator: It feels heavy, weighed down with emotion. But it is not a snapshot—this would have required skill and time, a clear artistic eye to construct and capture it all so deliberately. I wonder about the artist's motivations; was this for personal expression or perhaps for commerce? It sits somewhere between a document and an elegy, no? Editor: That tension, the oscillation between art, emotion, commerce and documentation, encapsulates much about photographic practices then. But also about the cultural moment itself. It's easy to interpret this photograph solely through its funereal tone, but the late 19th century saw an explosion in middle-class consumerism; items related to mourning and memory were marketable commodities. This changes how we interpret images like these—less like unvarnished, authentic grief, and more as objects circulating within consumer economies. Curator: Well, no matter the context, it does speak of finality. But within the grief there are these potent symbols of hope, reunion and love. Something very human in this desire to frame death itself. Editor: Indeed, from these traces, we understand not just lives and deaths, but societal mechanisms around handling both—something profoundly human in any age.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.