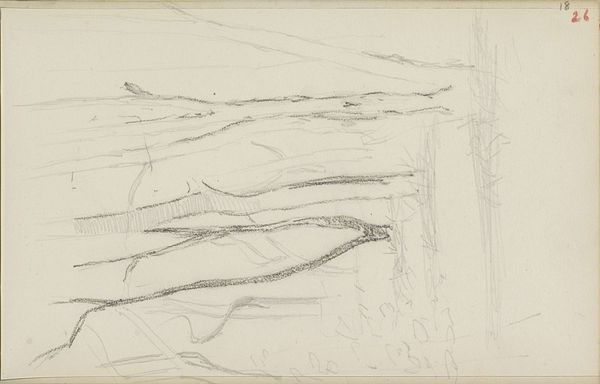

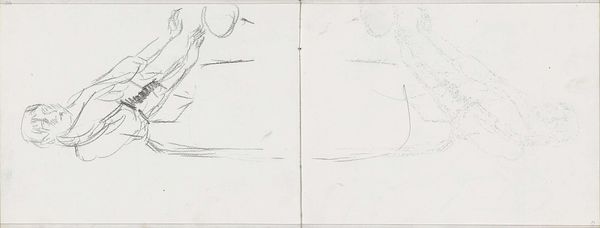

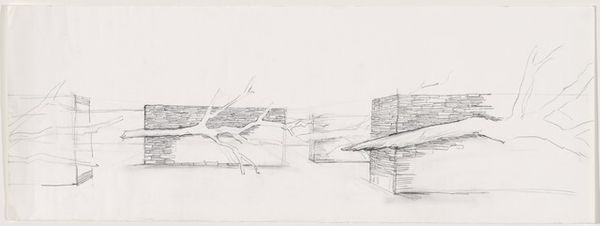

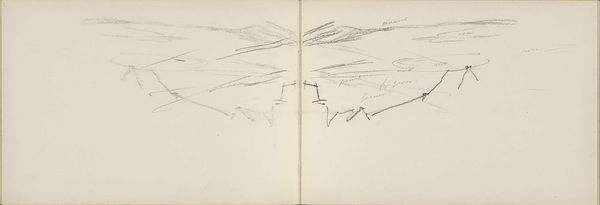

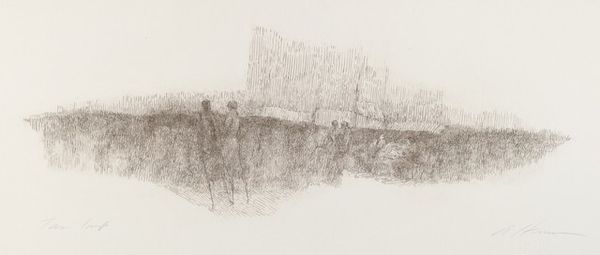

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

sketch

#

mountain

#

pencil

#

line

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: So, this is "Kulu Valley" by Nicholas Roerich, from 1929. It’s a pencil drawing. It's pretty sparse, almost minimalist in its depiction of mountains. What's your take? Curator: This drawing is really interesting because it's a prime example of the artist engaging directly with his environment through readily available materials. Look at the quick, almost frantic, pencil strokes. This suggests a need for immediacy, to capture the landscape as a visual record but also a visceral experience. Consider Roerich’s larger artistic project, concerned with cultural preservation. How does the material choice—a humble pencil—affect the perception of the grandeur of the Himalayas? Editor: That's a good point. It is almost like the roughness of the sketch mirrors the ruggedness of the landscape in a raw, unpolished manner. What does the "means of production" convey in this piece? Curator: Exactly. It challenges our expectations of landscape art. This isn't about idealized beauty achieved through laborious detail, it's about access and portability, about capturing a place within the grasp of readily available means. Roerich traveled extensively; a simple pencil sketch allows for on-the-spot documentation, a kind of artistic fieldwork. It asks, what is required to *make* art accessible, what work goes into making something seemingly effortless? And also, for *whom* is the work? Editor: I hadn’t thought about the accessibility aspect, but that makes so much sense considering Roerich’s wider concerns. It makes me see the drawing in a new light – not just a sketch, but a document. Curator: And not just any document but evidence of how artistic processes interact with labor and portability in shaping cultural meaning. It helps understand the value of this art as situated production rather than isolated inspiration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.