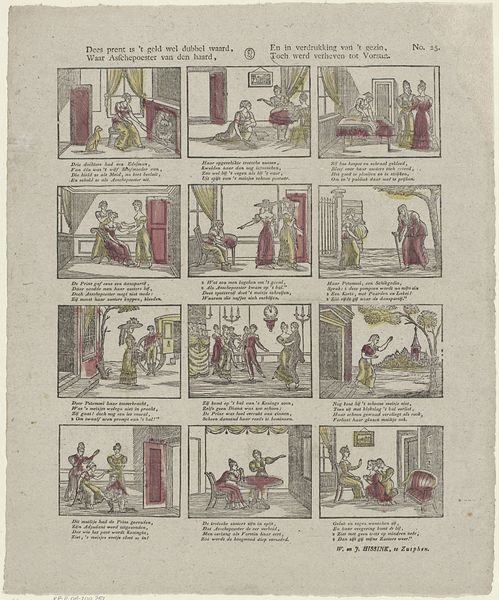

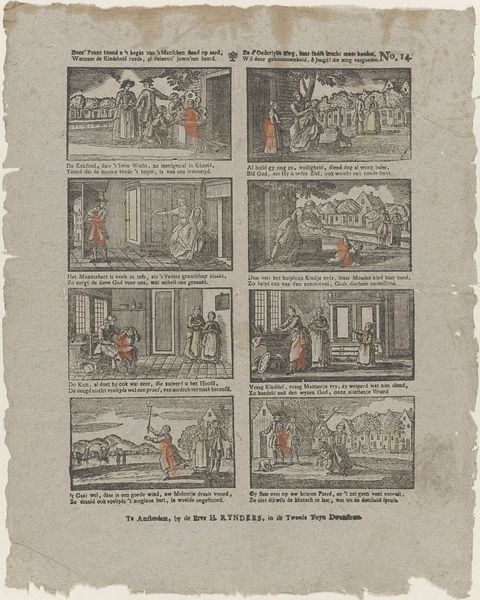

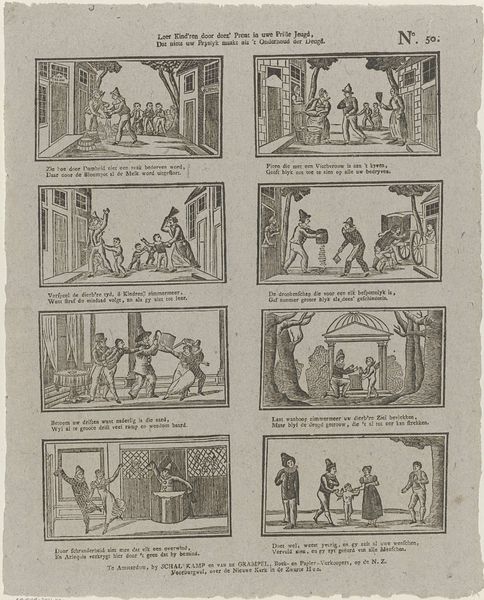

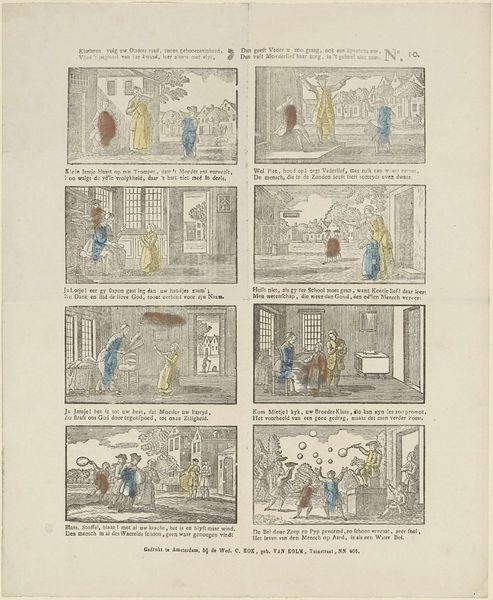

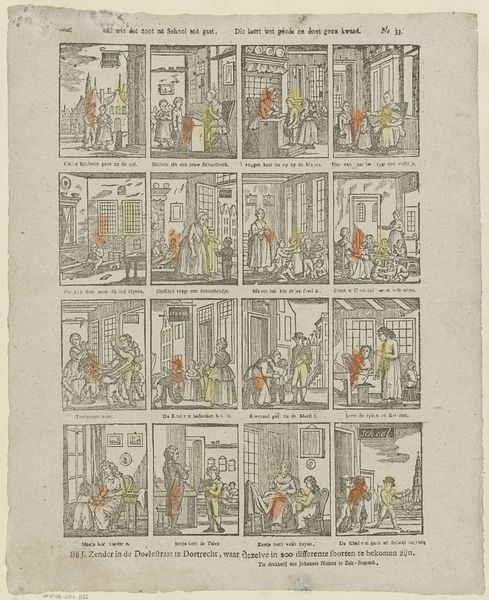

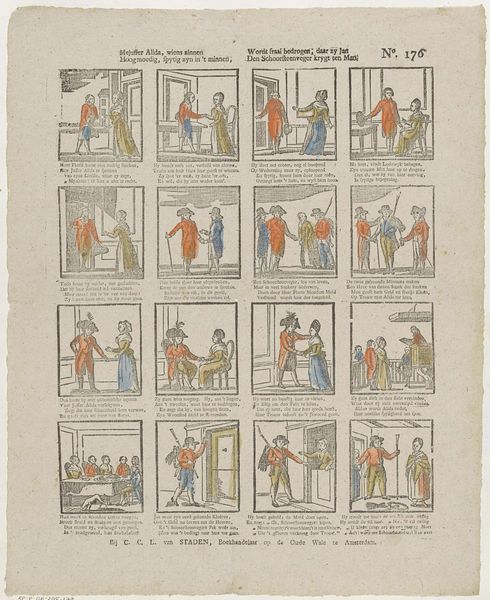

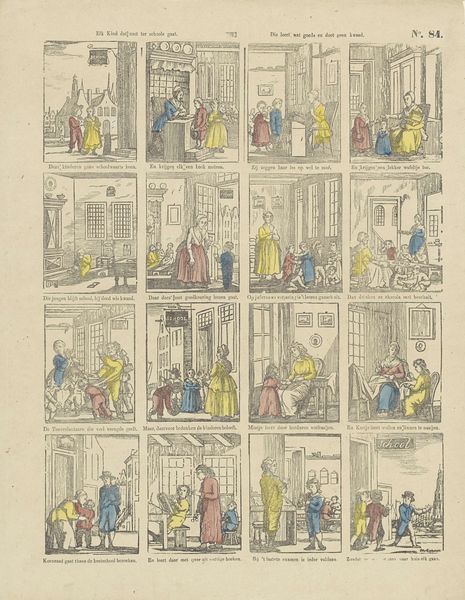

's Menschen Intreede op deeze waereld. / Deeze prent leerd uw, ô jeugd! wat ge in ryper tyd, / aan uw waardig Oud'ren paar dankbaar schuldig zyt, / Want van 't eerste oogenblik tot aan 's menschen dood, / Is het geen dat hy behoefd, alle dagen groot 1831 - 1854

0:00

0:00

ervehrynders

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print

#

graphic-art

#

narrative-art

# print

#

child

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 402 mm, width 325 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print by Erve H. Rynders, likely created between 1831 and 1854. The full title is quite a mouthful: "'s Menschen Intreede op deeze waereld. / Deeze prent leerd uw, ô jeugd! wat ge in ryper tyd, / aan uw waardig Oud'ren paar dankbaar schuldig zyt, / Want van 't eerste oogenblik tot aan 's menschen dood, / Is het geen dat hy behoefd, alle dagen groot." Editor: Wow, even visually, it's a lot to take in at first glance. It gives me a feeling of…domesticity tinged with something a bit didactic? All those little scenes packed together... it's like a visual sermon. Curator: It's essentially a series of vignettes depicting the different stages of childhood and the parent-child relationship. Think of it as a form of early mass media communicating values, especially parental gratitude, to a broad audience. Rynders operated his press in Amsterdam; so we might expect some reflection of the culture from which the artwork originates. Editor: Absolutely. I'm really drawn to how gender roles are being subtly reinforced here. I'm trying to read beyond those quaint domestic scenes. Do these images reinforce normative, gendered positions? What does this format reveal about the intended audience? Curator: A crucial question to ponder! These images and associated proverbs create expectations for familial structures and personal piety. They teach the child/viewer gratitude toward their parents for material care, and simultaneously position the parents as caregivers responsible for their offsprings physical needs and religious learning. Editor: The way childhood is presented here...it's like this long period of debt to be repaid to the parents later in life. It really speaks to the socio-economic realities. Did children enjoy fundamental rights in this community? Or were children primarily valuable for their contribution to a larger familial economy? Curator: Well, seeing it in our contemporary setting is essential to the value of the artwork. As society changes, it allows a deeper view and discussion about values then and values now. The fact that Rynders chose the format to teach us the stages and family make-up should stand out to us most. Editor: I find that notion so valuable to unpack as well. These small, mundane looking panels become this window into 19th century social expectations. Viewing this piece feels like a glimpse into someone else's family scrapbook, highlighting all their achievements, family milestones, challenges, losses...It's compelling.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.