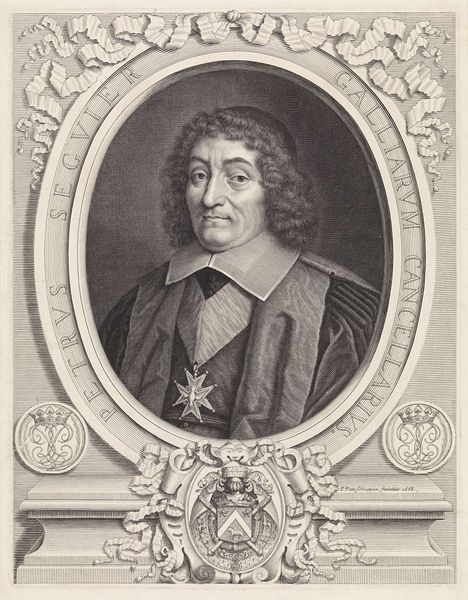

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

geometric

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 342 mm, width 255 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

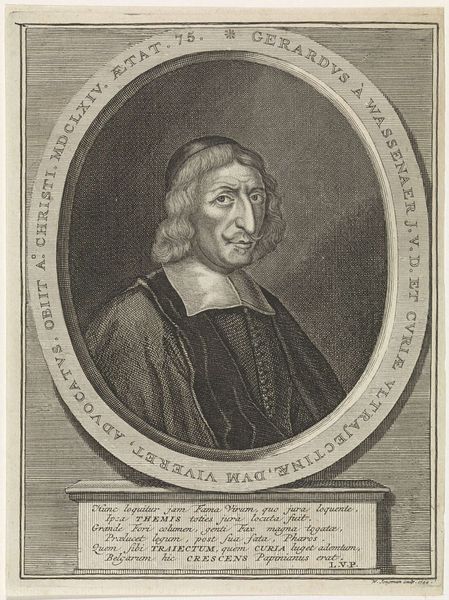

Curator: Andries Vaillant, a name perhaps not so familiar today, created this rather stately portrait of Aloysius Bevilacqua between 1675 and 1680. The artwork, titled "Portret van Aloysius Bevilacqua" is an engraving. Editor: It’s strikingly formal, isn’t it? The man, framed in that elaborately lettered oval, seems to exude a kind of contained authority. All that linework… it almost vibrates with subtle power. Curator: The formality speaks directly to its function within the 17th century social structure. Printed portraits like these served to disseminate the images of powerful figures, solidifying their positions and legacies. Consider the inscription, and the family crest; every element reinforces Bevilacqua’s status. Editor: Precisely. The crest and miter – undeniable symbols of lineage and ecclesiastical power, really nail that idea of the divine right of rule and inherent importance, don’t they? Note too how Vaillant uses linear hatching to define the textures and the light across Bevilacqua's face. It brings an almost unsettling level of immediacy. Curator: Absolutely. The artist skillfully utilizes engraving techniques. We observe academic art, the way he constructs a clear and legible image, intended to circulate widely and communicate very specific information. Editor: Yet, it's the somewhat severe expression that truly holds my gaze. What secrets do you think a face like that keeps? I mean, the symbolism is powerful, but it is that very controlled expression, the kind one hones in public life, that I am really drawn to. Curator: That severity, I believe, speaks to the gravity of his role. Bevilacqua isn't merely presenting himself; he's performing his public persona, crafting an image appropriate for historical record. It’s political theatre presented on paper. Editor: It does invite contemplation on power, doesn't it? Even the botanical wreath around the portrait gives this sense of cyclical honor. Interesting how the baroque gives birth to a kind of academic art that aims to reproduce, not question. Curator: Exactly. An exploration of that production is precisely how art helps explain society. Thank you, this insight allows one to pause and contemplate. Editor: My pleasure. Perhaps next we consider the individual behind those carefully chosen symbols, behind all the authority.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.