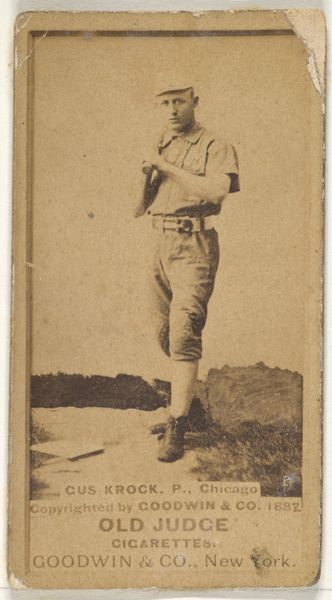

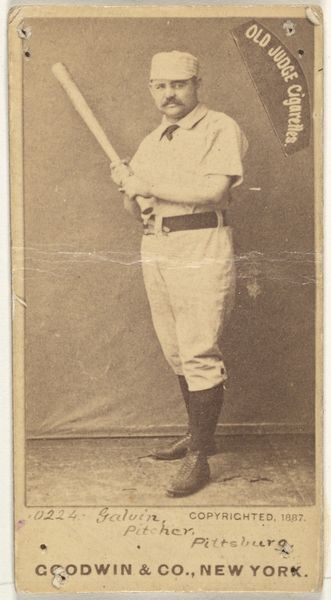

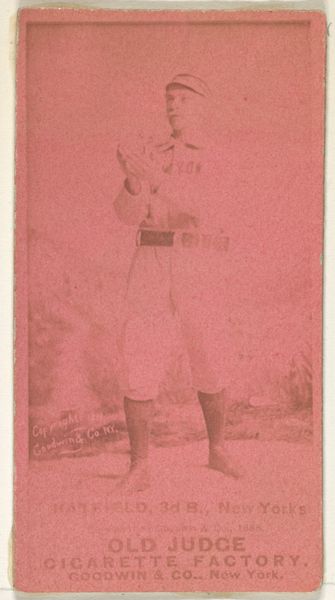

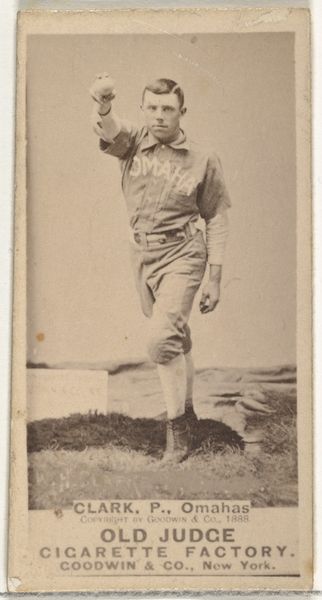

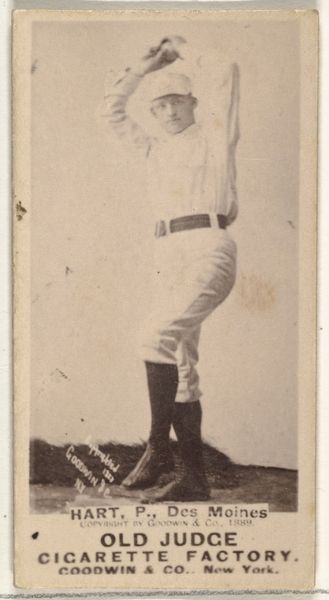

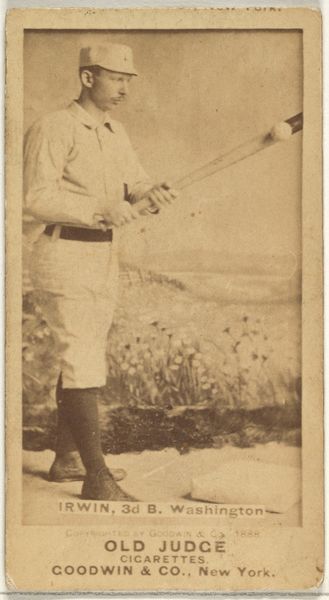

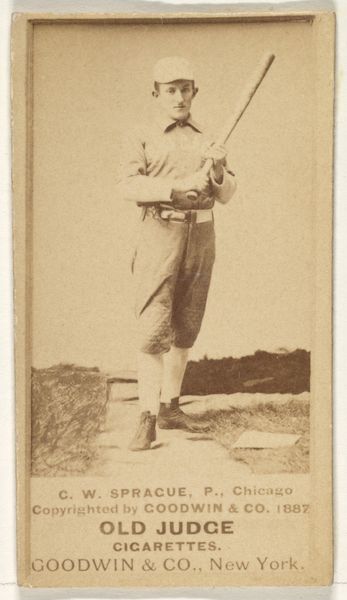

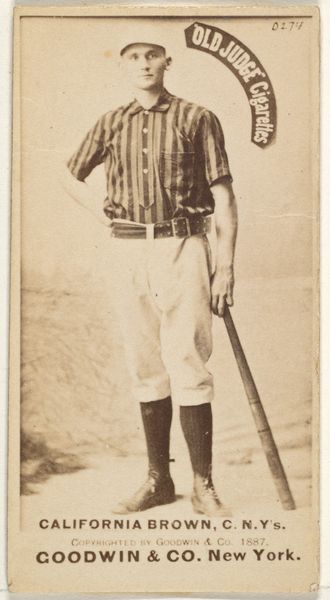

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

photo restoration

# print

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

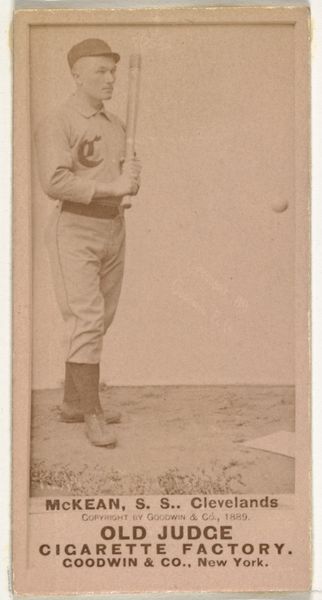

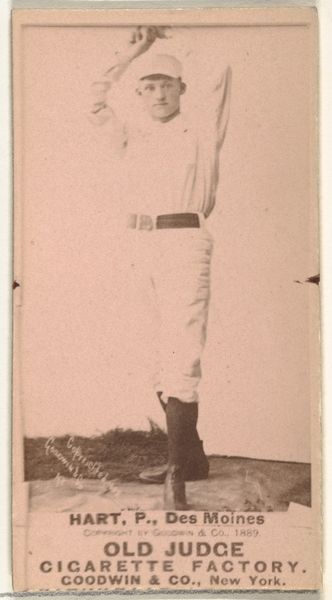

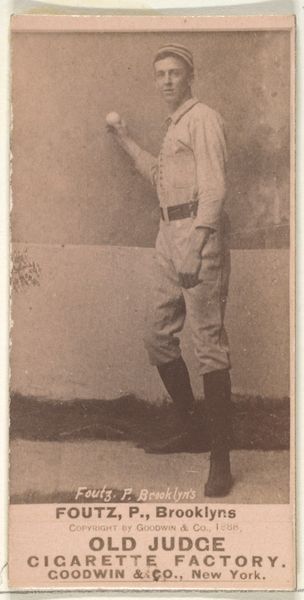

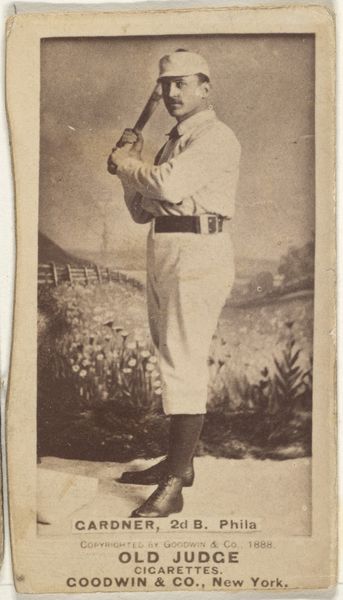

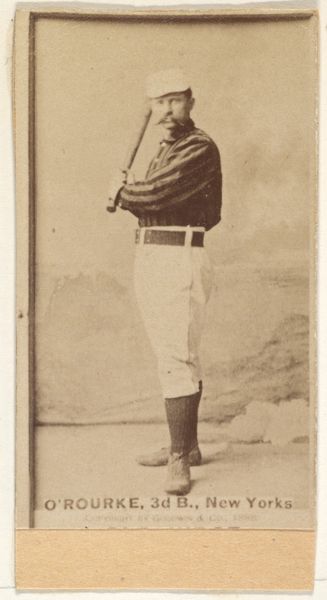

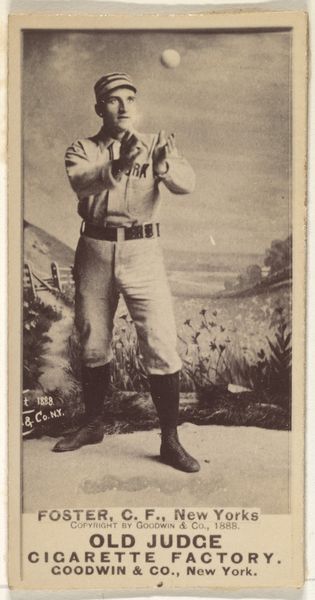

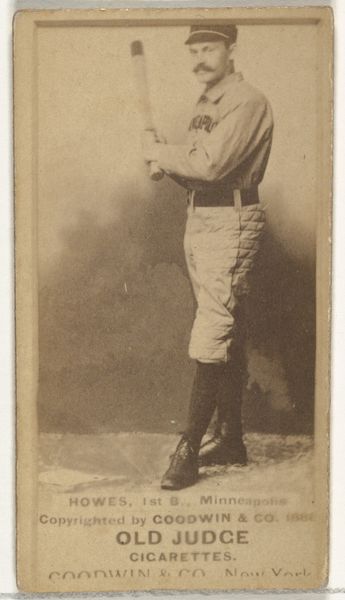

Dimensions: image: 8 × 5.5 cm (3 1/8 × 2 3/16 in.) sheet: 8.9 × 6.3 cm (3 1/2 × 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Standing before us is Mike Mandel's 1975 gelatin silver print, "Oscar Bailey." The image offers a glimpse into a specific time, inviting us to consider the context in which this work was produced and received. Editor: It strikes me as quite casual, almost vernacular. There's a directness to it—the texture of his knitted shirt, the weathered look. You immediately sense that it documents something of real, working-class life in America. Curator: Absolutely. Mandel's practice often engages with representation and the politics of visibility. This portrait raises questions about authorship and how we construct narratives around everyday subjects and their identities. What does it mean to frame someone like Oscar Bailey in this way? Editor: The printing process itself adds another layer. A gelatin silver print signals a traditional, almost documentary approach to capturing reality. It speaks to accessibility, it's a fairly reproducible method which may democratize images but requires very specific materials sourced from all around the world. Curator: The medium does seem deliberate here, grounding the image in a tangible, reproducible history. How do you think Mandel is relating to the labor present both within the portrait, Oscar’s implied work, and in the very act of making? Editor: Labor's woven into everything, isn't it? The knitted shirt probably wasn’t machine-made but rather handmade from synthetic fabric – which requires intense manual input as well! The act of photographing, developing, printing—it’s all human intervention transforming raw materials. But there's the larger, perhaps unspoken context of labor too... what kind of work did Oscar do, how does it reflect on this community and these places? Curator: Precisely. And what are the visual signifiers he's chosen? The baseball cap, the casual knit... How might these have been perceived in the '70s, in relation to shifting cultural and political identities, notions of masculinity, of working-class culture. Is this presenting him as an individual, or standing in for something more collective? Editor: It prompts reflections about authenticity, about claiming working life, the materials people surround themselves with daily – things both humble and monumental, that leave traces, revealing something about social relations. Curator: I find myself reconsidering how portraiture itself can serve as a tool, both for preservation and potential manipulation of image and representation across time, especially as photographic portraits were getting into every magazine by the 70s. Editor: It's like a coded message isn't it, about who we value enough to create and preserve a record of – and with which specific means. A truly telling image, once we dig beneath its surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.