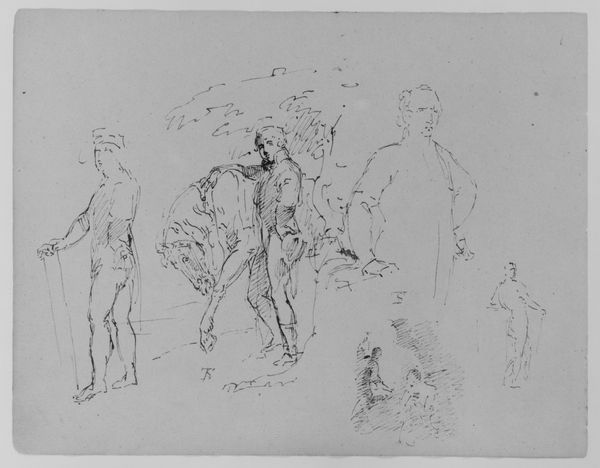

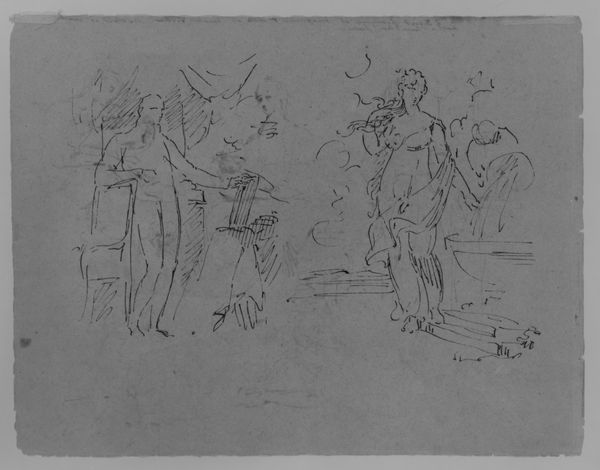

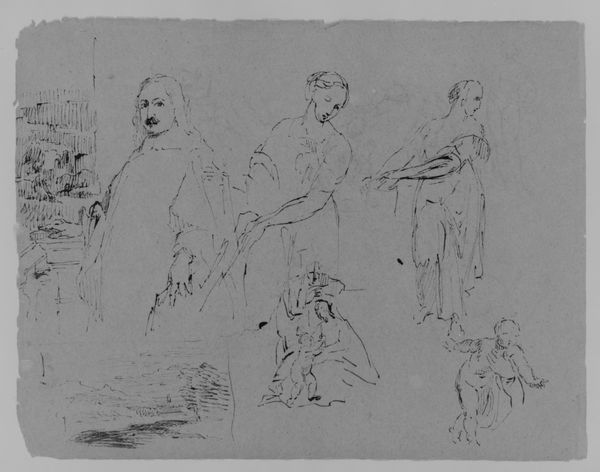

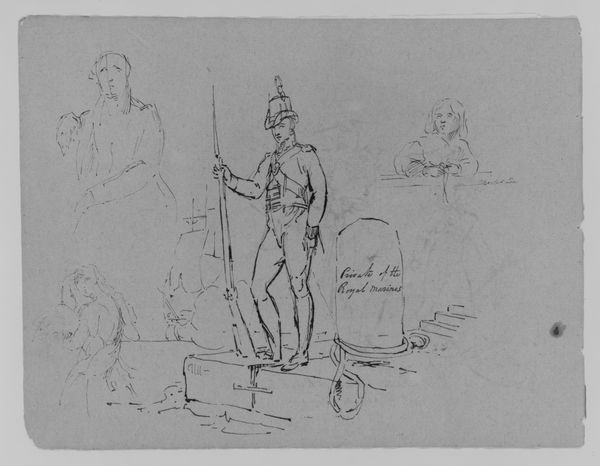

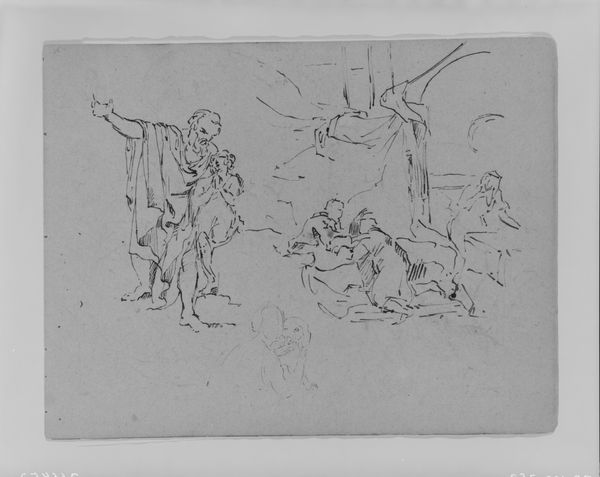

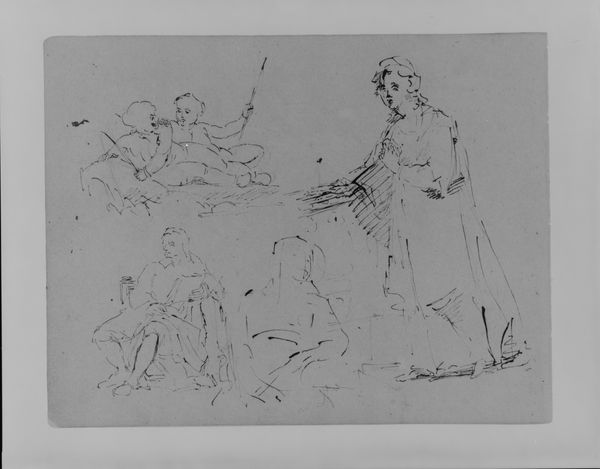

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

Dimensions: 9 x 11 1/2 in. (22.9 x 29.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

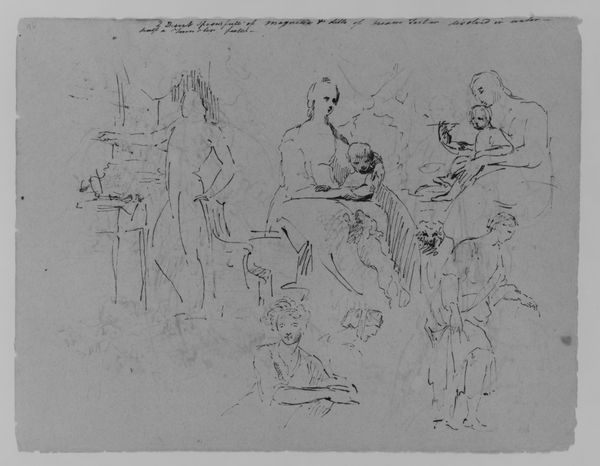

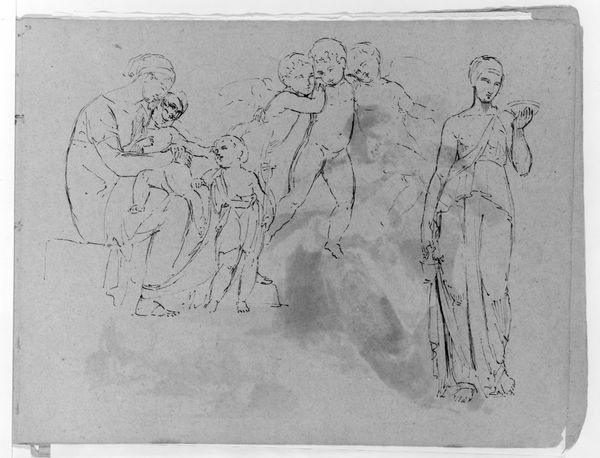

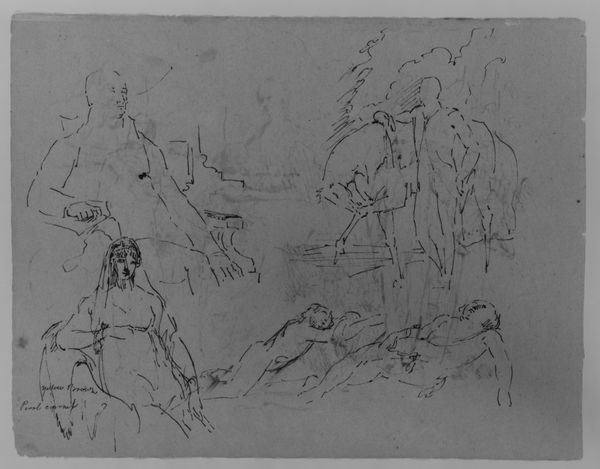

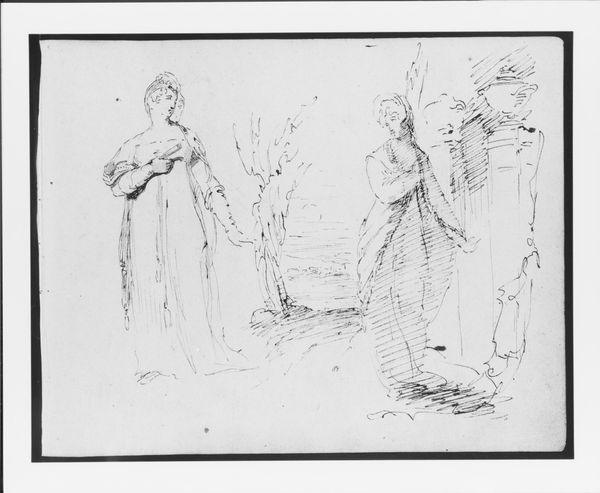

Curator: Thomas Sully, a painter celebrated for his portraiture, rendered this work on paper with ink around 1810 to 1820. The piece is simply titled "(From Sketchbook)." What are your immediate impressions? Editor: I am struck by the loose, almost frenetic energy of the drawing. The figures are suggested more than defined, lending a sense of dynamism and perhaps a touch of Romantic-era drama, fitting for the style. Curator: Indeed. Given that this is from a sketchbook, we’re witnessing the artist’s initial explorations, not a finished work meant for public display. It reveals his process, showing multiple figure studies, seemingly unrelated. I find myself thinking about Sully's own positioning within the social structure and class politics of early 19th-century America; who were his patrons? How does this work challenge or support them? Editor: That's interesting! And to add to your idea, if this piece truly reflects a private, unfettered expression, then the presence of these male figures asks us to reconsider performative gender roles and perhaps masculine power structures in that era. Could Sully have been critiquing the status quo through the language of Romanticism? Curator: It's worth considering. His formal portraits, destined for salons and political spaces, would have been subjected to intense social and institutional scrutiny; these sketchbooks allowed him more autonomy. They show that beyond commissioned art, Sully has social reflections to offer. Editor: Precisely! Looking at the man holding the cane, for instance, is he an authority figure, a representation of wealth, or simply a study of pose and deportment? It’s open to interpretation and dependent on the viewer's own framework. Also, the way Sully uses negative space around each figure suggests both their individual existence and their interconnectedness, it feels almost poetic. Curator: Absolutely. Sully’s sketch beckons us to excavate layers of meaning while examining the artwork itself as a material artifact. Editor: This piece really speaks to how something unfinished, almost off-hand, can be deeply compelling in a way a formal, resolved work maybe isn't.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.