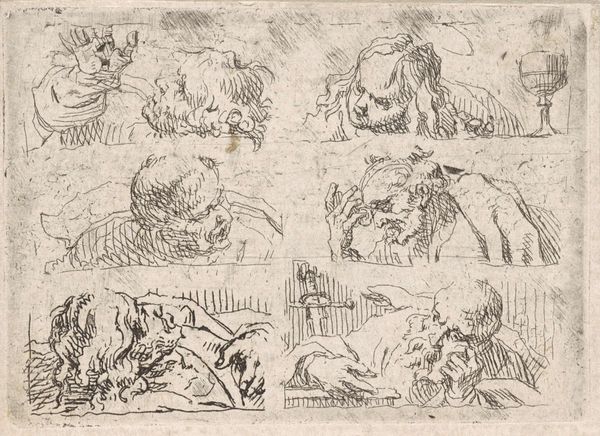

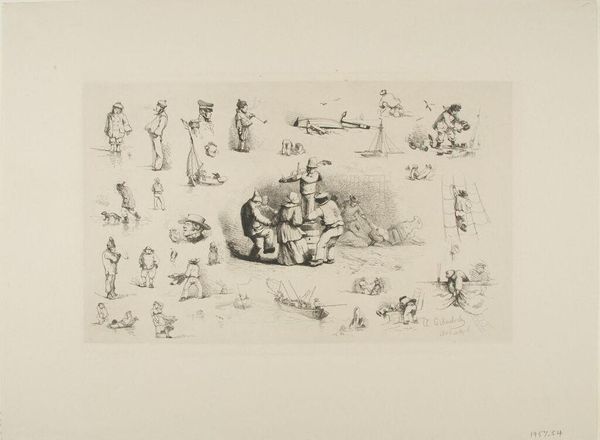

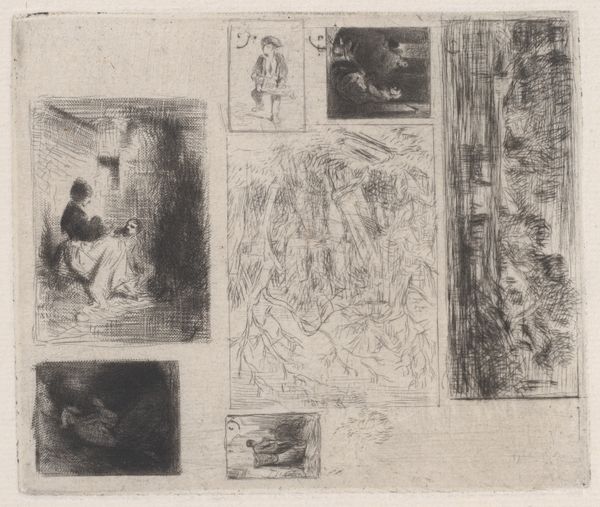

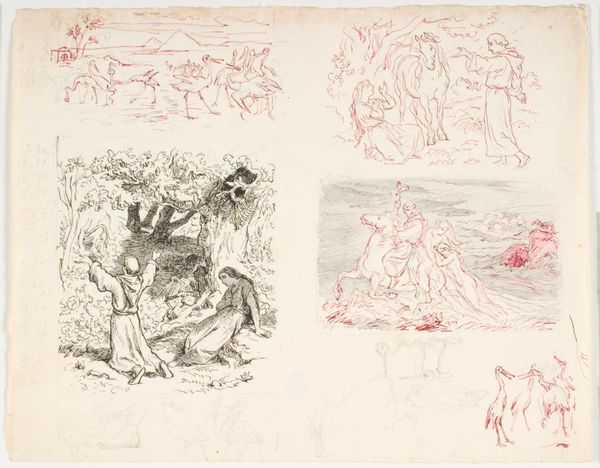

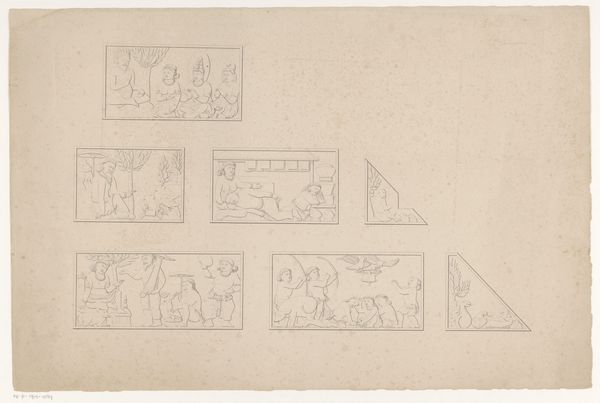

print, etching, ink

#

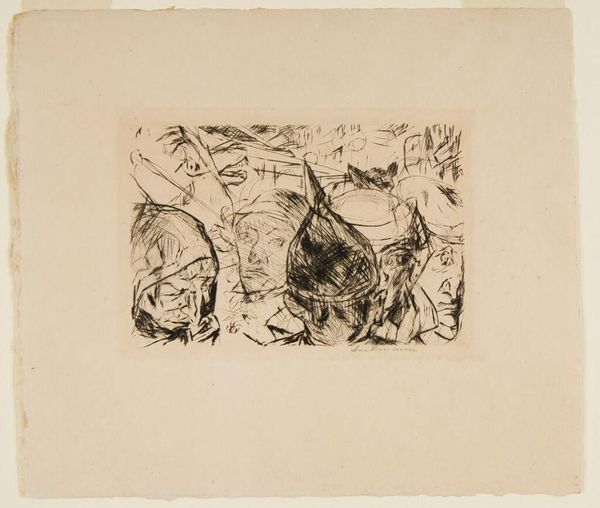

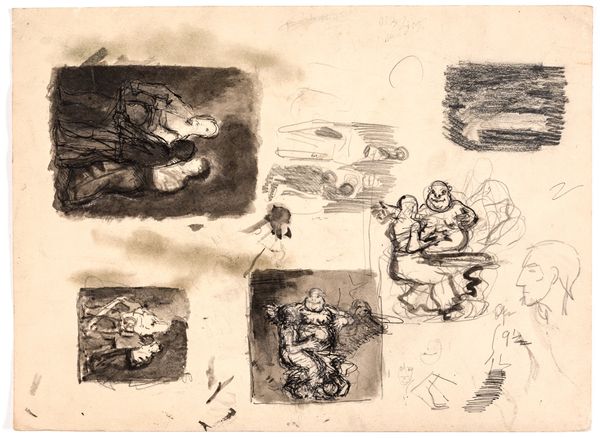

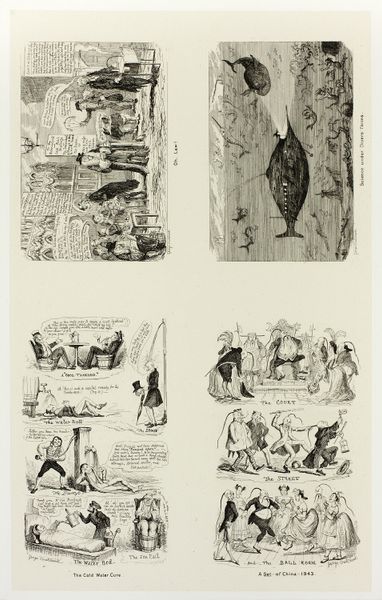

cubism

#

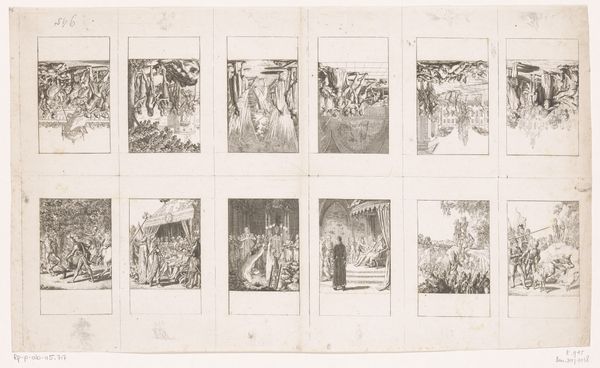

comic strip sketch

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

figuration

#

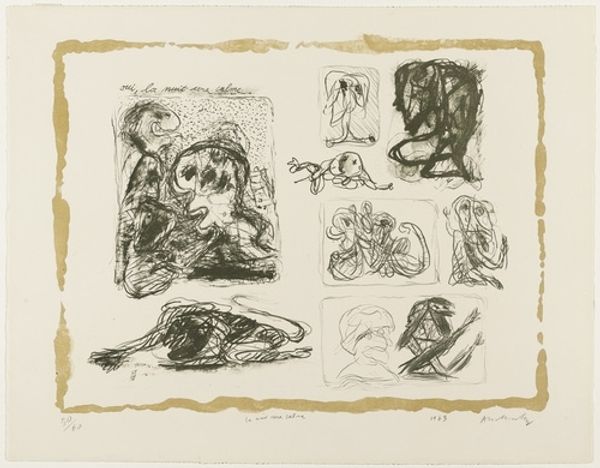

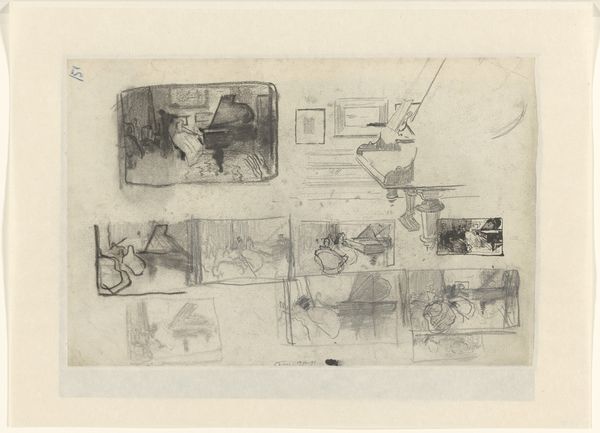

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

abstraction

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

surrealism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at Picasso’s "Dream and Lie of Franco I," created in 1937, I’m struck by its rawness. It feels almost like looking into someone’s tormented sketchbook. Editor: Tormented is right. It’s chaotic, a jumble of images fighting for space. My initial feeling is unease; there’s nothing restful about this work. What do you make of the comic strip format? Curator: It's deliberate, I think. The panel layout ironically packages the nightmare of Franco’s rise in a format often associated with lighthearted storytelling. These aren't innocent cartoons; they are charged political statements. Each vignette shows the monstrous absurdity of fascism. It makes you wonder, doesn’t it? Editor: The stylistic shift between panels is compelling. Look at the harsh lines in the panel depicting the screaming figure versus the more fluid, almost dreamlike quality of others. What's the purpose? Curator: It feels like a deliberate disruption, visually mimicking the disorienting nature of propaganda and violence. By varying the style, Picasso avoids a singular narrative, suggesting the multifaceted horrors of the conflict. I read it as Picasso refusing a neat, easily digestible account of trauma. It splatters onto the page. Editor: Let's talk materials: etching and aquatint on paper. It lends the piece an interesting texture, but it's also inherently reproducible, making it accessible, almost like a broadside. Is that part of its power? Curator: Precisely! The accessibility aligns perfectly with its political purpose. This wasn't meant for a museum; it was intended as a weapon against indifference. Making art political like a bomb of protest. He really sets up the power struggle that never disappears! Editor: Thinking about the imagery, those hybrid creatures, the distorted figures... It feels very surreal, but pointedly so. How much is abstract horror and how much direct commentary? Curator: I'd say they’re intertwined. The abstraction allows Picasso to move beyond literal representation. The Minotaur-like figures, the weeping woman – they symbolize the brutality and suffering inflicted by Franco, but they also resonate on a primal, universal level. It really does capture all that it needs. Editor: It leaves you feeling hollow in the pit of your soul. So, would you say this still speaks to us today? Curator: Absolutely. The "Dream and Lie of Franco I" is a reminder of the power of art to confront tyranny, and its visual potency is proof that art, especially in political turmoil, is a very moving form.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.