drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 385 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

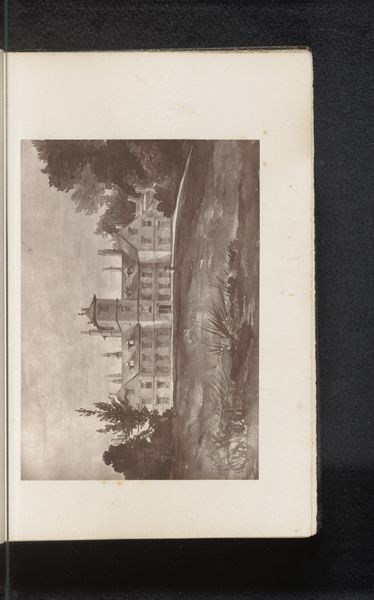

Curator: Petrus Josephus Lutgers created this etching titled "Kasteel Loenersloot" in 1832, a moment steeped in Romanticism. The piece is expertly rendered, showcasing impressive technical skill in printmaking. Editor: My first impression is one of serene stillness. The water is so calm it mirrors the castle perfectly, and the tones create a sense of quietude. It’s almost dreamlike, yet grounded. Curator: The choice of etching is particularly relevant, wouldn’t you agree? Consider the accessibility it provided during the 19th century. It was a mode of production allowing for relatively easy reproduction and distribution. Here we have an image made for, and readily available, for the rising middle classes. Editor: Absolutely. Etching facilitated wider access to landscape imagery. Looking closer, you can almost feel the texture of the paper itself. The labor invested is remarkable, if we are speaking about access, because it evokes questions of skill. Who did that labor serve? Who controlled the castle and by extension the local people at the time of its depiction? Curator: It certainly prompts those lines of inquiry. Beyond the method, Lutgers utilizes a subdued palette which invites us to meditate on the history of architectural grandeur and land ownership represented in the castle as a site of authority and perhaps even a space for negotiation. I think it provides the opportunity to talk about these buildings as ideological artifacts. Editor: Right. There is definitely that negotiation embedded here as well as, to a certain extent, an affirmation of power. Notice the people included are relegated to staffage. We have, essentially, the fisherman at the edge and the men in the boat near the center who provide us with some reference point in terms of scale, in a very humble way. The focus is ultimately about architectural details. It gives us information about design, about materials of production... stone, glass, the layout of the land. The scene becomes, in its totality, almost propagandistic, doesn’t it? Curator: Propagandistic, or perhaps even aspirational, I find myself wondering what these particular people felt seeing this piece knowing they were not allowed to come closer than what we have here represented. A point of intersectionality perhaps when it comes to architecture as experienced and architecture as rendered. Editor: Food for thought, certainly. As our material interactions with art transform over time, it's intriguing to consider how its original audiences might have engaged with its materiality, then and now. Curator: Indeed. These prints open a complex and nuanced landscape of art-making within systems of value and historical moments.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.