print, plein-air, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

outdoor photograph

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

couple photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: 27.8 × 19.7 cm (image); 42.6 × 33.4 cm (paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

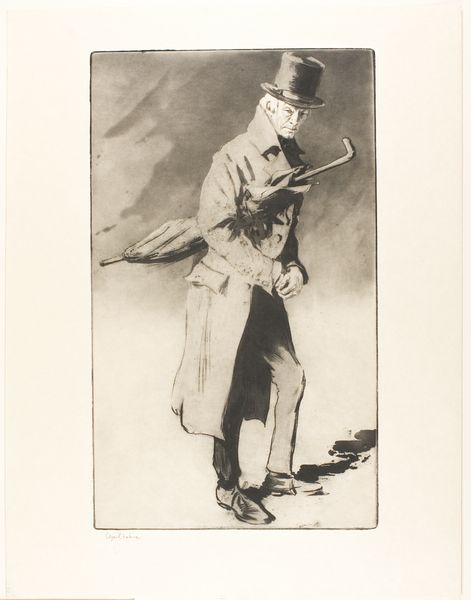

Curator: Standing before us is Peter Henry Emerson’s “Haymaker with Rake (Norfolk),” a gelatin-silver print dating from approximately 1883 to 1888, and residing here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s incredibly evocative. The pose, the overcast light… It speaks of labour and quiet endurance. Curator: Absolutely. Emerson was a key figure in the photographic movement that sought to establish photography as a legitimate art form. This image comes from his documentation of rural life in East Anglia. He tried to promote photography that demonstrated artifice and manipulation through chemistry during printing to add to pictorial effect to try to legitimize this form. Editor: And you see that emphasis in the way the man's figure is softened. His tools and labouring body rendered with dignity – and visible. It is interesting how his clothes display evidence of labor and wear. How his pants hang a bit, maybe they once belonged to another member of his family, making them too big. It suggests an honesty, or at least an attempt to engage an audience that understood toil. Curator: That's precisely it. Emerson’s project engaged with larger debates regarding the changing landscape of Britain. Rapid urbanization forced agricultural labourers to look towards working within more mechanized means or leave farming behind altogether. His subjects, and photographic aesthetic, become symbols of something eroding in the society around him. Editor: There is a nostalgia embedded within the work too. The image seems so posed, in a world of photographs. To think that a moment could stop completely still seems disingenuous to me when thinking of what a man working truly looks like, so he may be constructing this fantasy. He seems sturdy but contemplative, not broken by the weight of the day, almost posing a challenge to those consuming it. Curator: Yes, it speaks to a complex relationship between observer and observed. Emerson came from privilege; this work forces us to question his representation and how he attempts to construct some idea of a lost English identity. What did it cost this haymaker to stop his labor so someone can observe? What stake does this haymaker even have in its eventual circulation? Editor: Thinking about the cost involved… the man’s labour to produce the hay, then Emerson to set this scene. Ultimately that work is what connects me most to this image, these layers upon layers of material transformation that we continue to grapple with even to this day. Curator: It is those critical intersections that ultimately offer such resonance for viewers. A truly remarkable piece with deep-seated ramifications in terms of the historical role of laborers within both the photographic landscape, but also how this plays on England as an agricultural nation in the nineteenth century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.