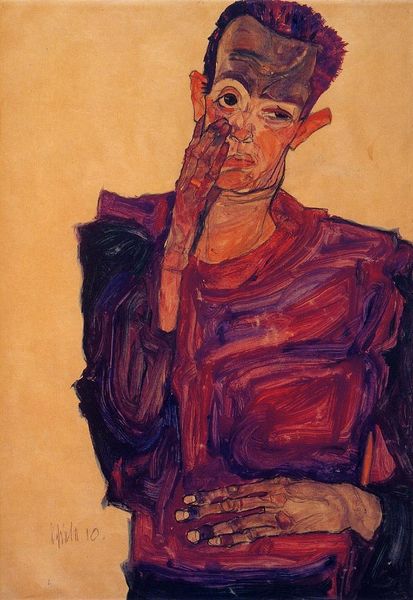

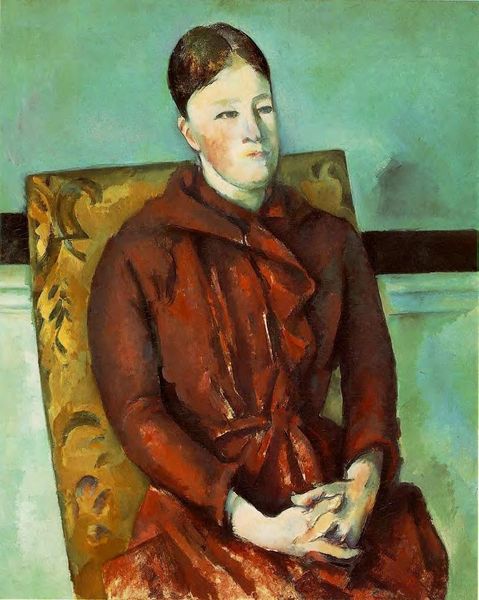

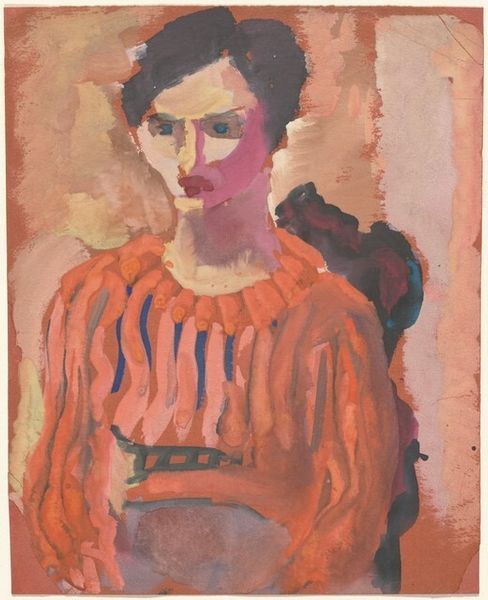

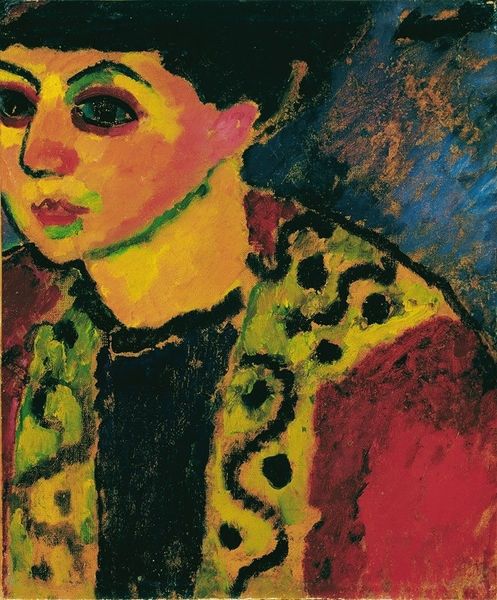

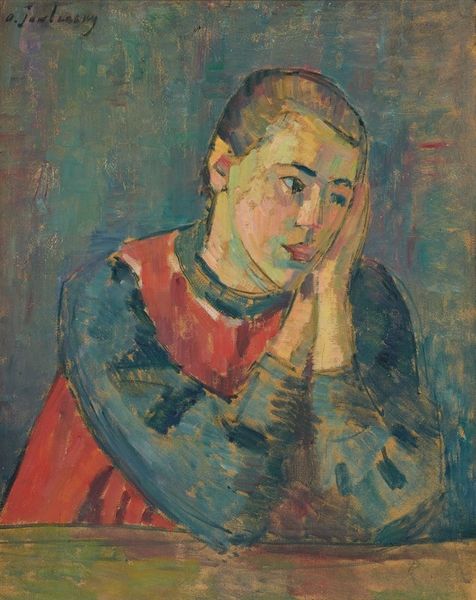

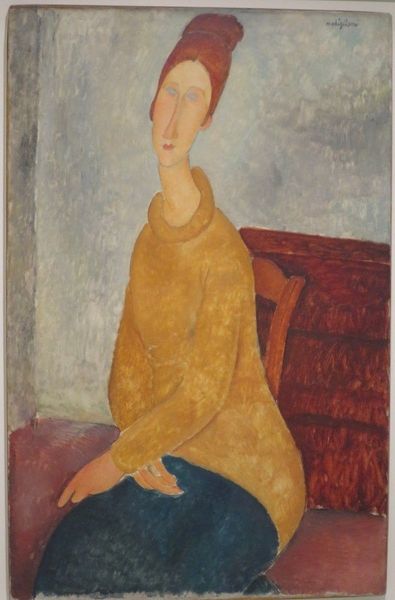

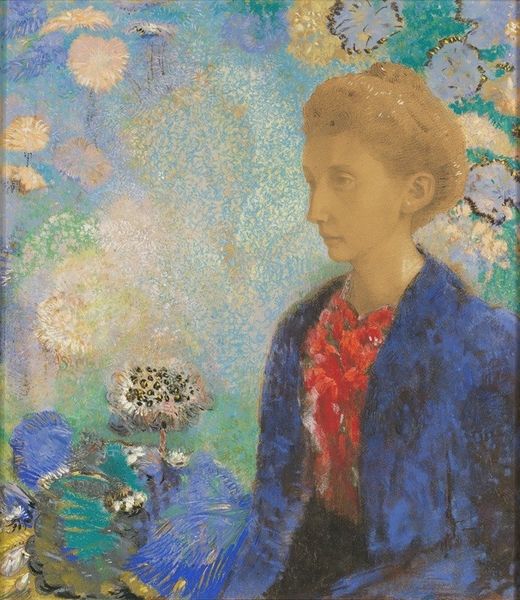

painting, oil-paint

#

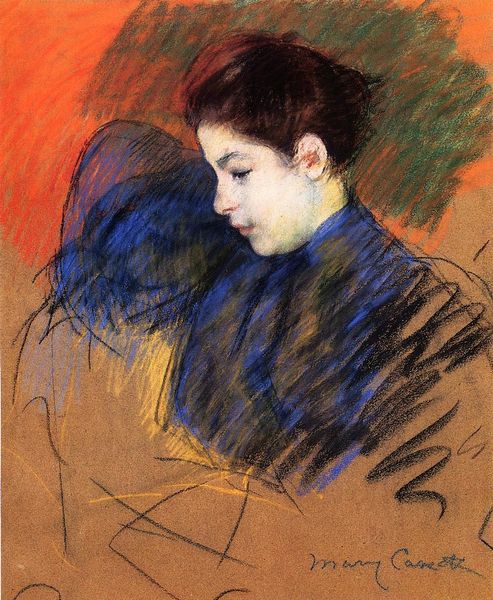

portrait

#

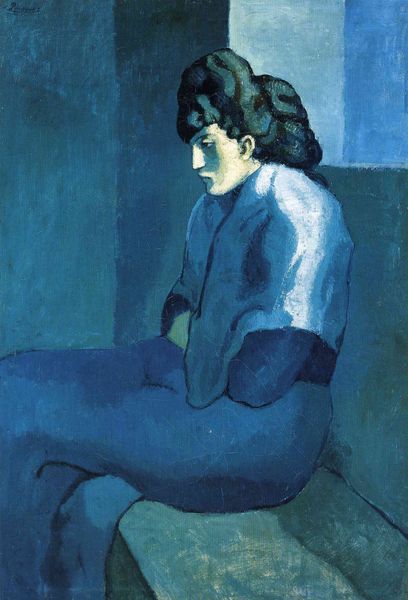

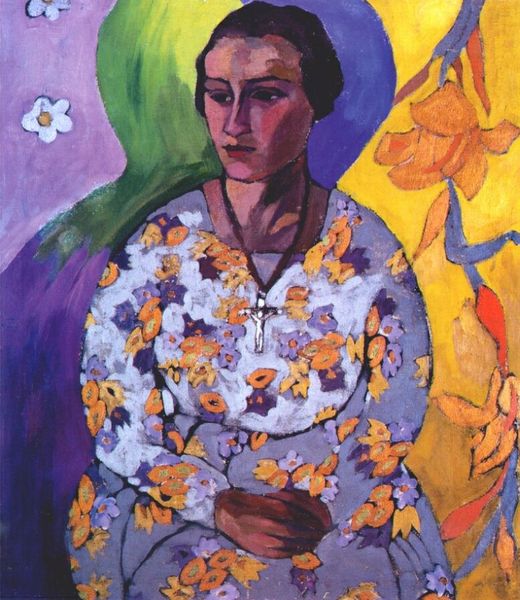

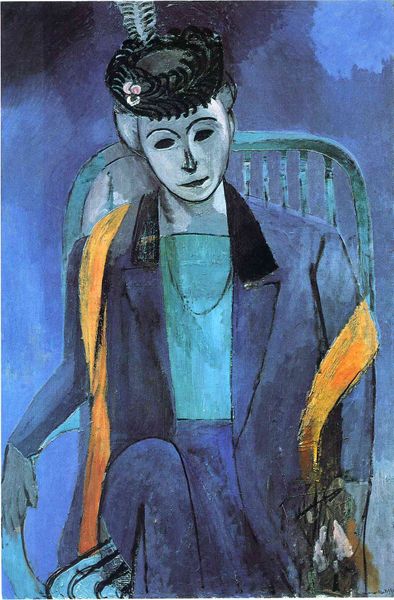

cubism

#

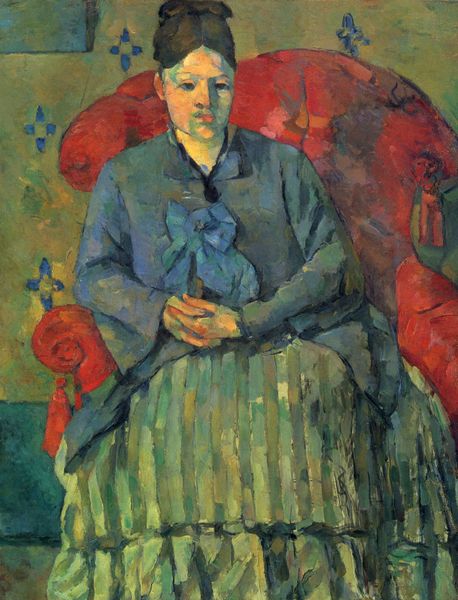

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

early-renaissance

#

portrait art

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: 100 x 81.3 cm

Copyright: Public domain US

Curator: Picasso painted "A Boy with Pipe" in 1905, and it marks a transitional moment in his career, painted toward the end of his Rose Period. He uses oil on canvas here, in a departure from the earlier Blue Period’s somber palette. Editor: The color is definitely the first thing I notice. That warm reddish-orange backdrop, clashing almost aggressively with the cool blue of the boy’s outfit... there’s an undeniable tension. He doesn’t look entirely comfortable. Curator: Right, it’s a fascinating juxtaposition. The flowers, the wreath—these are all emblems traditionally associated with celebration, but on closer inspection, the boy himself looks rather withdrawn, detached. Perhaps this contrast reveals Picasso's deeper explorations. Do you notice anything about the Renaissance influence that emphasizes symbolic expression? Editor: Definitely. You see that in the almost idealized presentation of youth, the softening of features, yet the contemporary clothing undercuts any attempt at grand narrative. Who was this kid? Picasso seemed fascinated by marginalized figures – was this simply romanticizing poverty? Was he more than that? I'm curious about identity and class in this particular moment in early modernism. Curator: Well, the boy is reported to have been a local named "Petit Louis", who frequented Picasso’s Montmartre studio. He provided an accessible subject. There’s a debate as to the extent Picasso was interested in authentic representation or simply using these subjects for his aesthetic experimentation. This work has the feeling of iconography with contemporary interpretation and context. The pipe itself has been said to have multiple cultural references; the symbol of trade, peace, escape and much more. Editor: This reading is certainly interesting considering that this work went on to become one of the most expensive pieces of art. With that added layer to the meaning, do you find it disturbing at all, that he, "Petit Louis" who was arguably on the lower rung of society has now ironically created a legacy worth so much in capitalist valuation? Curator: Yes, I am definitely not able to unsee it. The piece of his time became an ironic twist of our reality and our place in modernism. What a piece. Editor: A testament, ultimately, to art’s uncomfortable ability to reflect our own society’s complex relationship with worth, value and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.