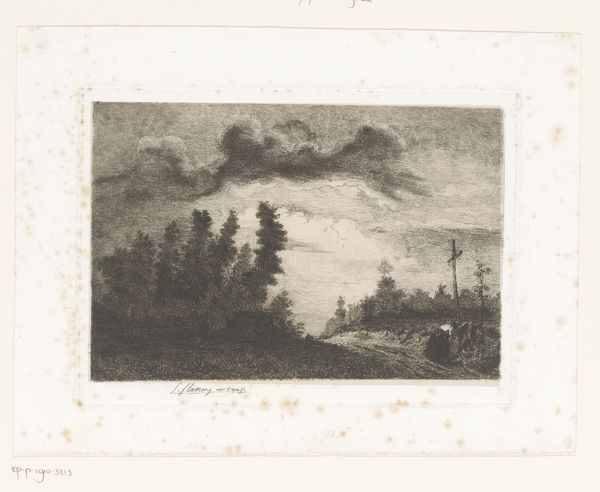

Dimensions: height 224 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What an evocative print. We are looking at "River Landscape with Dark Sky" by Wilhelm Wörnl, likely created between 1859 and 1916. It’s an etching, a testament to the artist’s mastery of capturing light and shadow. Editor: It's somber, isn’t it? Almost brooding. The looming sky presses down, and there’s a sense of isolation in that lone river cutting through the landscape. A premonition, maybe? Curator: Absolutely, the mood speaks volumes. Remember, landscapes in this era weren’t merely picturesque. They often served as coded commentaries on the social order, or the relationship between humanity and the divine. Romanticism used nature to reflect inner emotional turmoil, and question societal shifts following the industrial revolution. Editor: Right, so beyond just pretty scenery, the choice of such a darkened sky… I'm curious, what would this landscape have meant to its initial viewers within the cultural milieu of the time? Who did Wörnl intend to speak to, and what dialogues about modernity, gender, and societal role was Wörnl subtly engaging in, if at all? Was this just a technical display of Romantic affect, or a veiled form of protest against rapid change? Curator: That’s precisely the critical lens we need. Prints allowed for wider dissemination, making art more accessible to the middle classes, many unsettled by rapid urbanization. The etching process itself, requiring meticulous work, was seen to be aligned with a renewed appreciation of handicraft amidst rising mechanization. It is as if this melancholic view seeks to mourn something already gone, something forever changed. Editor: And Wörnl's choice of an etching--with that demanding intricacy— positions the piece, potentially, as an artistic assertion that challenges ideas of gendered production... How the work might offer critiques of industrial alienation and prompt considerations about female identity and agency against backdrops of broader socio-economic and cultural changes. It becomes much more than just scenery. Curator: Indeed. It invites us to reconsider art's potential as not just aesthetic object but a conduit for change and social conversation, using romanticism as its aesthetic vernacular. The artist becomes a commentator as well as a craftsman. Editor: Beautifully put. It's easy to get lost in the chiaroscuro, but the true depth comes from the socio-political undercurrents it reflects. Curator: Precisely. I'm always fascinated by the artist's ability to imbed statements, through his command of subject and material.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.