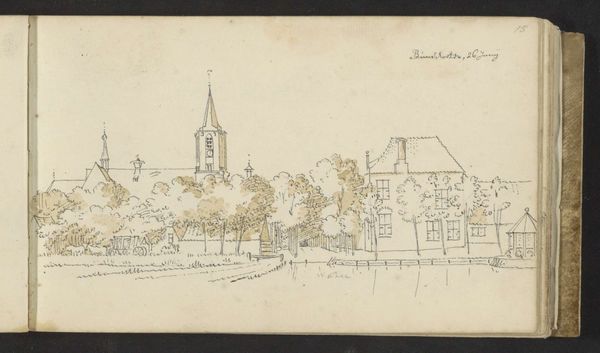

drawing, ink, pen

#

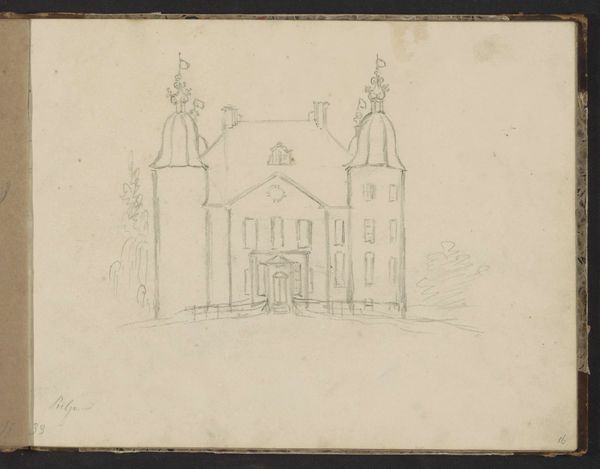

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

baroque

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

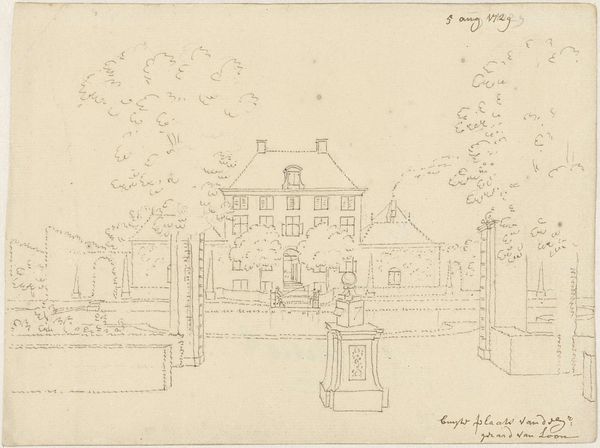

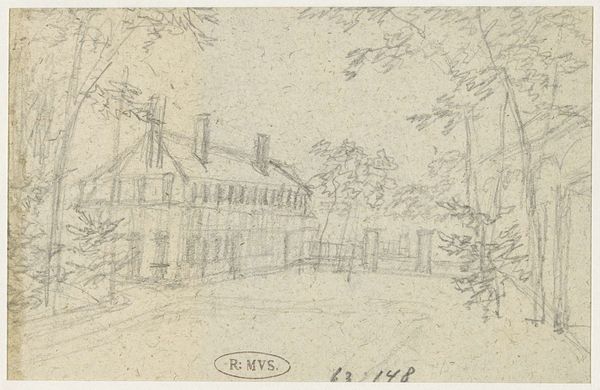

Dimensions: height 149 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Cornelis Pronk's pen and ink drawing, "Buitenplaats van Gerard van Loon; vooraanzicht," possibly from 1729. It depicts the facade of a grand estate. The drawing has this ephemeral, almost ghostly quality. What do you see in this piece, considering the period in which it was created? Curator: It's crucial to see beyond the pretty façade and understand what these estates represented in 18th-century Dutch society. They were symbols of immense wealth accumulated through colonial exploitation and trade. Does the rigid symmetry, the controlling of nature, perhaps speak to you of power, hierarchy, and exclusion? Editor: I hadn't considered the colonial context so directly. I was focusing on the aesthetics and the sort of formal garden design. But what you're saying makes me reconsider the underlying message. Curator: Exactly! Think about who *didn’t* have access to these meticulously planned "natural" spaces. How might their lived experience contrast sharply with the idyllic scene Pronk presents? The gardens aren't just decorative; they're statements of control – control over land, resources, and people. The landscape reflects social structures and injustices. Does that shift your perception of the work now? Editor: Absolutely. It’s not just a drawing of a pretty house, it's a document that inadvertently reveals power dynamics and systemic inequalities. The act of depiction becomes a political act itself. Curator: Precisely. By critically examining these visual records, we can begin to unravel the complex layers of history and their continued impact on the present. Editor: I'll never look at a landscape drawing the same way again! There’s so much more to unpack when considering the social implications behind the aesthetic.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.