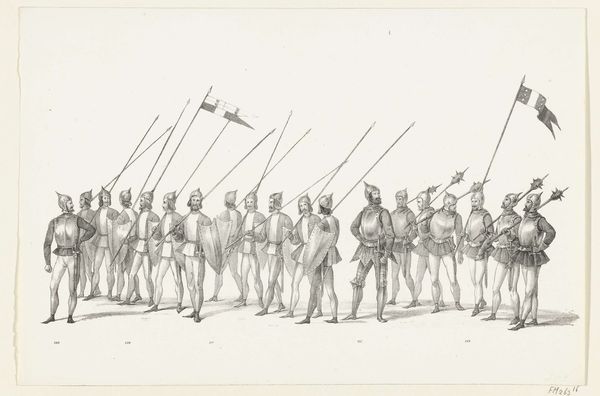

Schutters van het vendel van kapitein Abraham Boom en luitenant Oetgens van Waveren, 1623 1800 - 1882

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 528 mm, width 860 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

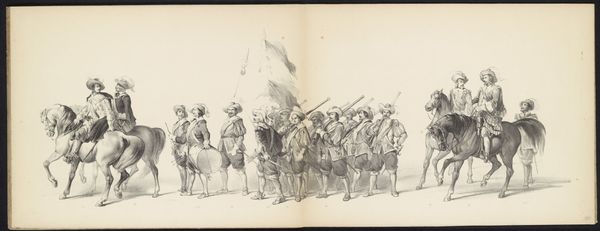

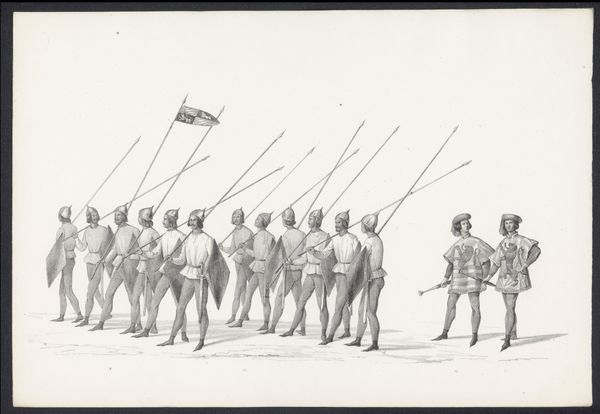

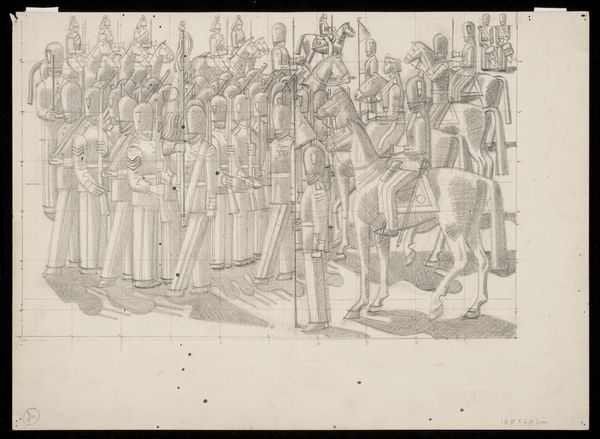

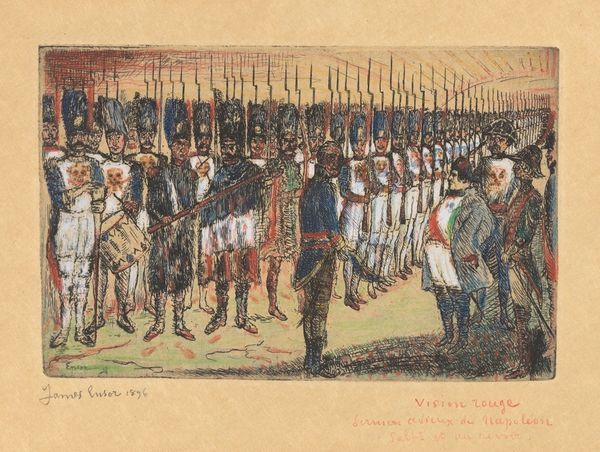

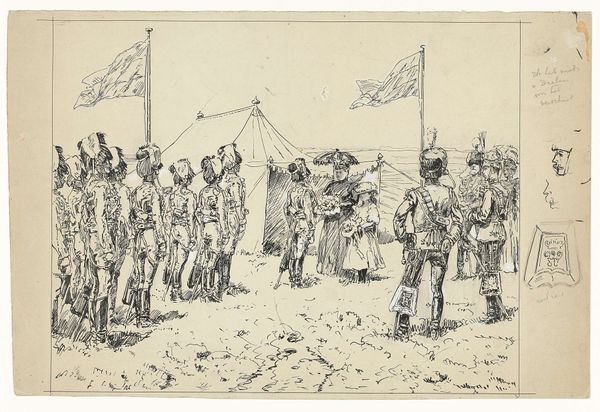

Curator: Here we have a fascinating print, "Schutters van het vendel van kapitein Abraham Boom en luitenant Oetgens van Waveren, 1623." Created sometime between 1800 and 1882, its execution involves ink on paper, crafted with pen and other techniques. It shows a gathering of civic guards. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is its somewhat muted palette. The gray washes create a formality. It's a study in somber colors, given that it's a later rendition of the robust Dutch Golden Age aesthetic. Curator: Precisely. Civic guard portraits were incredibly important for demonstrating not just communal identity but also civic power. Consider how the arrangement, even in this rendering, echoes the importance of these figures to the state, representing the individuals' involvement within municipal governance. These commissions often functioned as affirmations of status and belonging within a network of social relations. Editor: That performative aspect really jumps out. They're not just posing; they're constructing a particular image of themselves, complete with their status signifiers. Notice their dress; swords; those rather uncomfortable-looking ruffs? How does this depiction reinforce ideas about masculinity and citizenship during this historical context? Curator: A relevant question to probe! The original Dutch Golden Age portraits often emphasized qualities of strength and preparedness through detailed depictions of weaponry, confident stances, and commanding expressions. This version carries forward such codes; notice how weapons, armor, and hierarchical arrangements demonstrate clear class stratifications. Editor: And what about those ruffs? It's funny how a symbol of status can appear ridiculous from a later era, don't you think? Are they statements of conformity to gendered ideals? What might those standards say about patriarchal power in 17th-century Netherlands? Curator: Those garments serve multiple purposes simultaneously, from displays of affluence to declarations of social adherence. The way a figure positions their body, how one wields their weapon, the amount of lace or detail--all feed into a lexicon communicating place and self-understanding to contemporaries. Even within this redrawing done much later, that embedded language of social station retains power. Editor: It really underscores how much art serves as a kind of historical document, encoding social relationships in aesthetic forms, even here. Thanks for helping unpack these historical echoes within it. Curator: Thank you; indeed, this picture resonates even generations later, when its representation echoes our own shifting views on privilege, governance, and belonging.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.