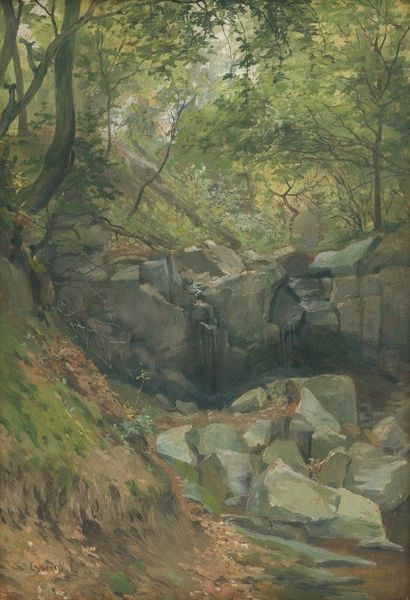

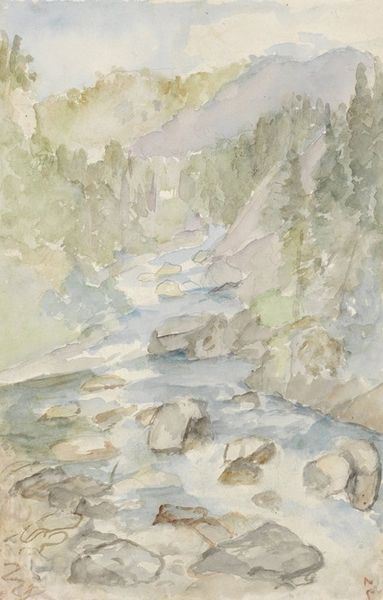

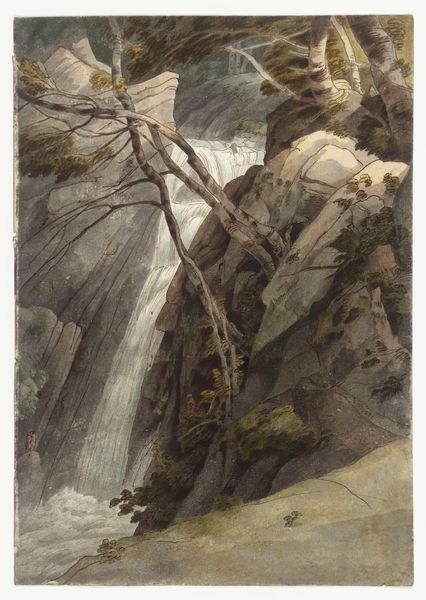

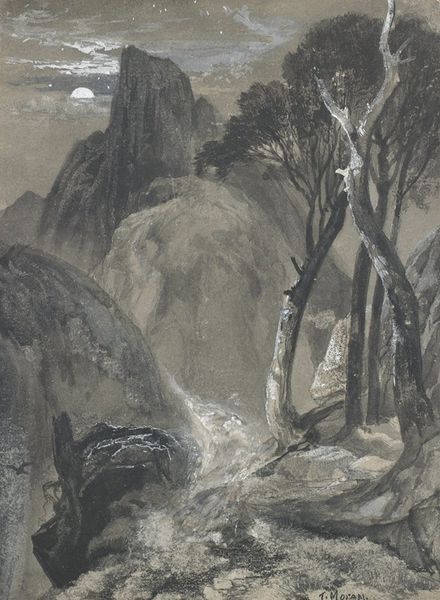

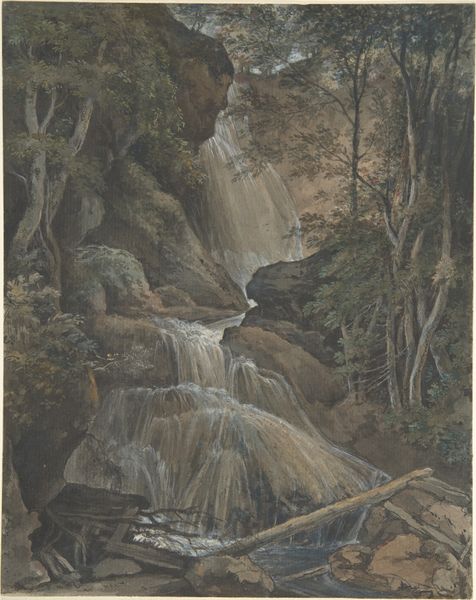

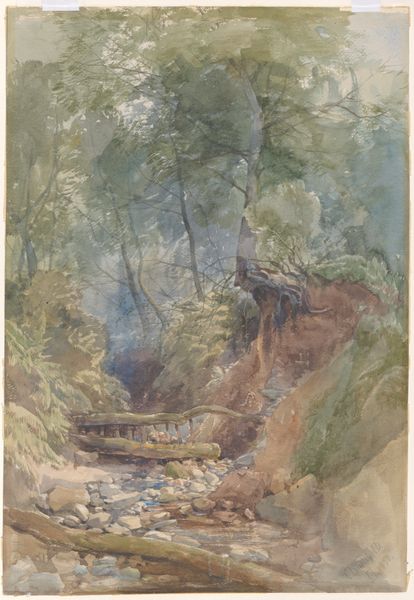

plein-air, watercolor

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

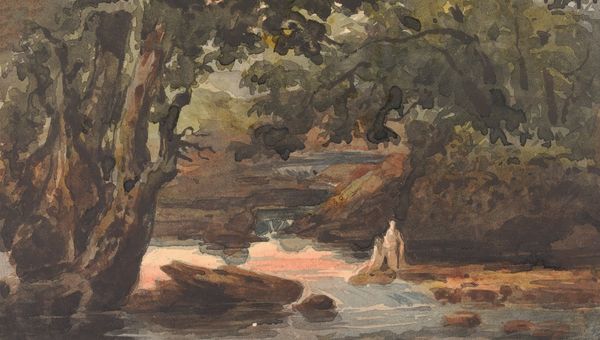

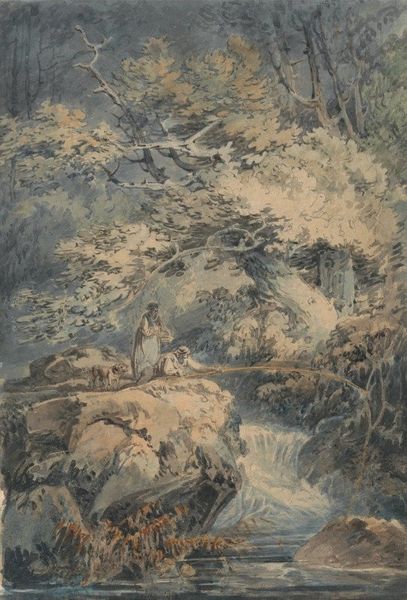

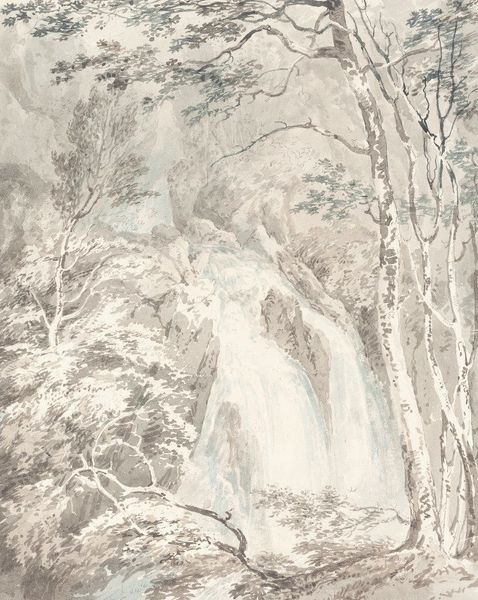

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: This delicate watercolor piece is titled "Small Waterfall in Forest" attributed to Thomas Sully. Its origin and exact dating remain uncertain, which in itself adds another layer to its narrative, don’t you think? Editor: Absolutely. My immediate reaction is one of serenity, almost meditative. The way the light catches the water creates this ephemeral quality, despite the defined, rather rough edges of the rocks. Curator: I find that interesting because Sully, within the context of the period, frequently turned to nature, as did his contemporaries, using these scenes not simply as aesthetic exercises but loaded with socio-political and philosophical meanings relating to ideas of nation, individualism, and the sublime. Waterfalls as sites of power are very common at this time. Editor: I can see how that fits into broader artistic trends and societal dialogues. The painting definitely invokes Romanticism. But beyond those established readings, do you think we could interpret the work's "unfinished" quality, this somewhat rough approach, as challenging conventions in our modern perception of what it means to fully "represent" a landscape and its intrinsic power? What is omitted, perhaps even elided? Curator: A potent argument! Considering what it omits, such as clear details, helps expose how "nature" might operate symbolically for certain classes and genders but remains closed off to others within a white heteropatriarchal society. For some, these vistas of nature are sites of contemplation and leisure; for others, such access and safety were far less straightforward, then and now. Editor: That sense of privilege and access, always so central, brings us to think about public lands. Did representations such as these—watercolors destined to be shown to a genteel class in urban contexts—serve as documents meant to influence access and management? Were paintings such as these instrumental in developing a land ethic for conservation, for example? Curator: That’s key—highlighting the very active public role paintings held. Sully and others like him helped formulate a perspective that helped dictate conservation policies but often reflected very biased approaches. The way Sully handled light and shade does draw our eye to a particular sense of idealized grandeur, masking a good bit of complexity. Editor: It really emphasizes how much of the significance we ascribe to art arises not just from the subject itself, but the matrix of its production and viewing context. Curator: Indeed. Engaging with its history also brings in many relevant aspects to critically examine the art and even how it shapes our own experience of landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.