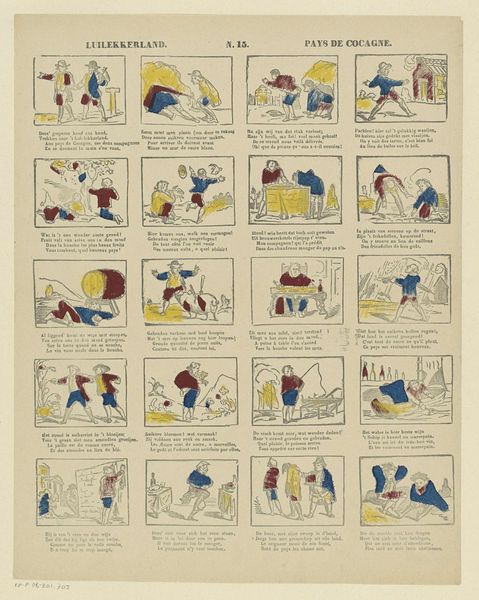

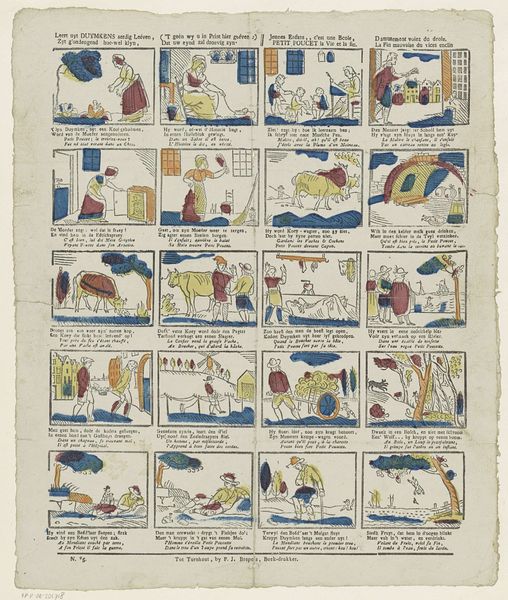

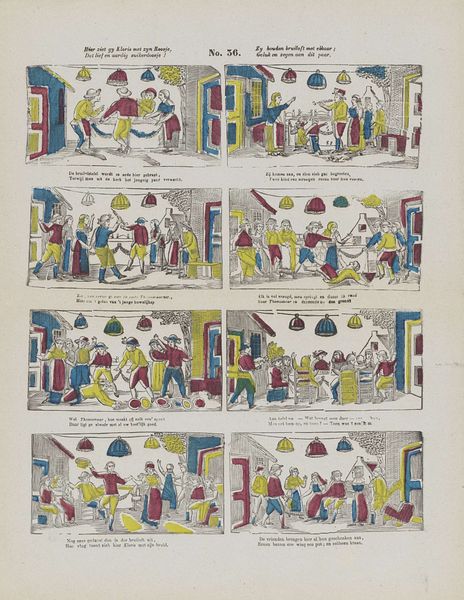

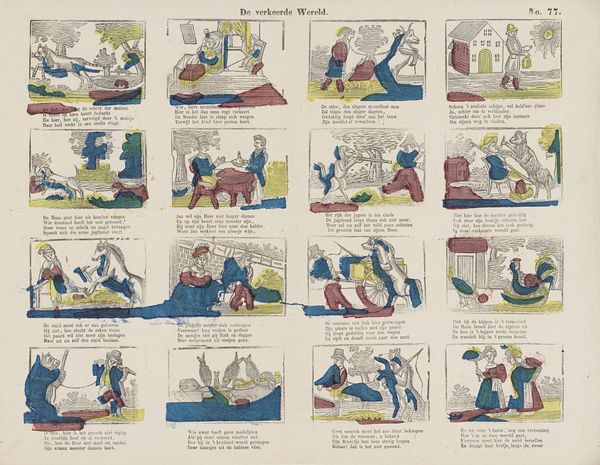

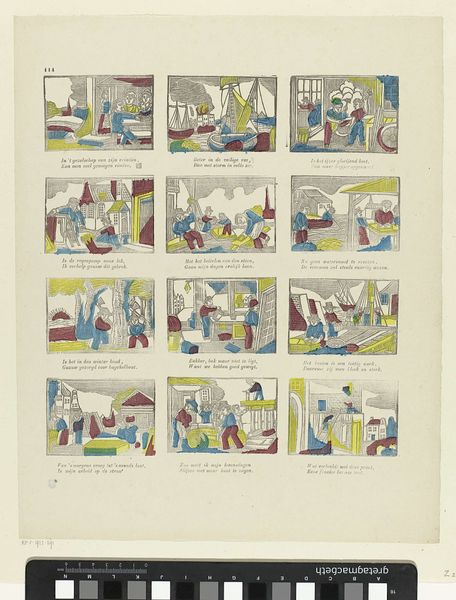

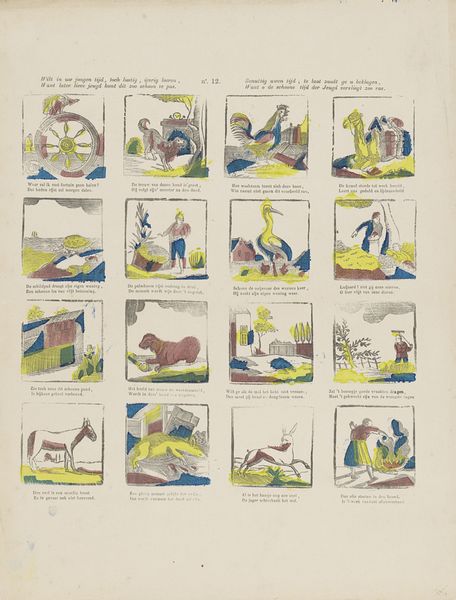

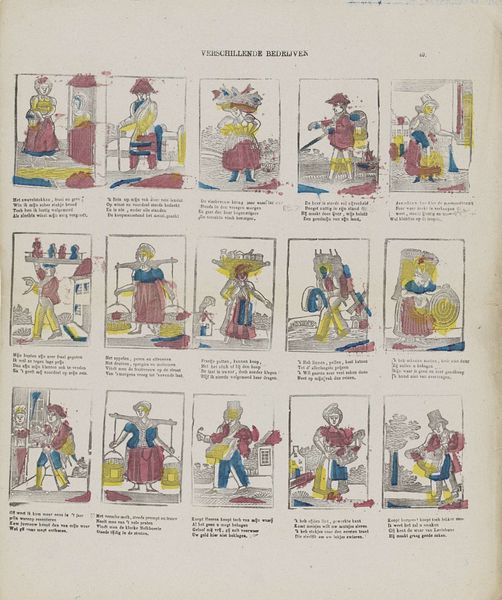

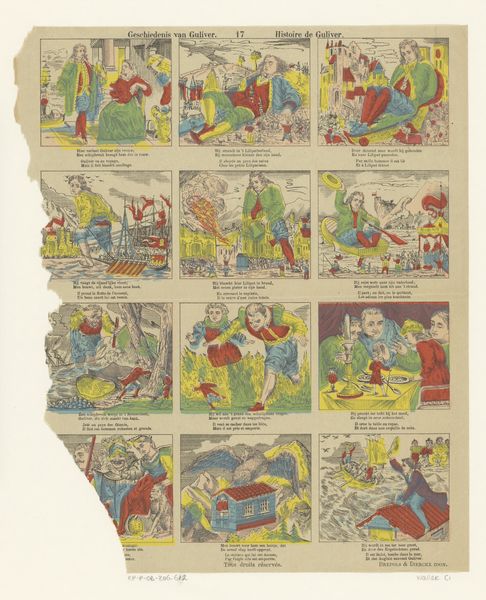

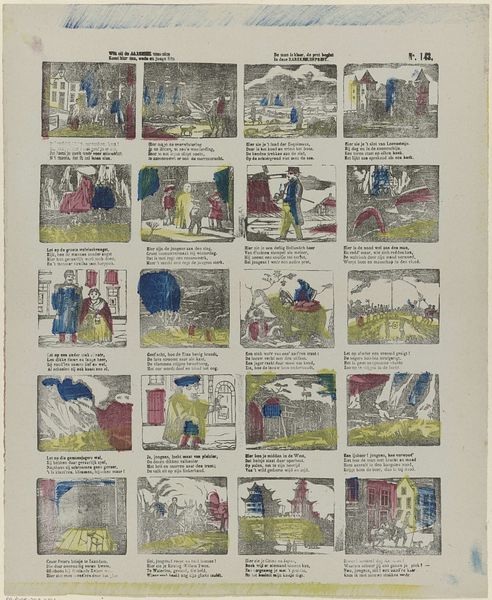

Leer, jongheid, hoe de deugd, geprent in d'eerste jaren, / De mensch uit 't nedrig stof tot d'eersten stand doet varen / Apprenez, par ceci que la vertu conduit, / A la gloire aux honneurs, et que le bien s'en suit 1800 - 1833

0:00

0:00

philippusjacobusbrepols

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 381 mm, width 308 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

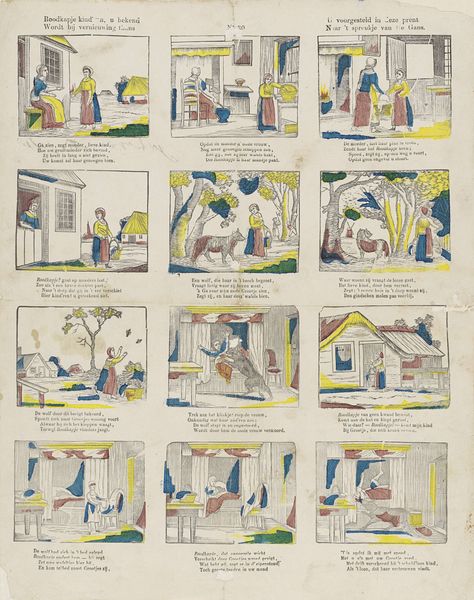

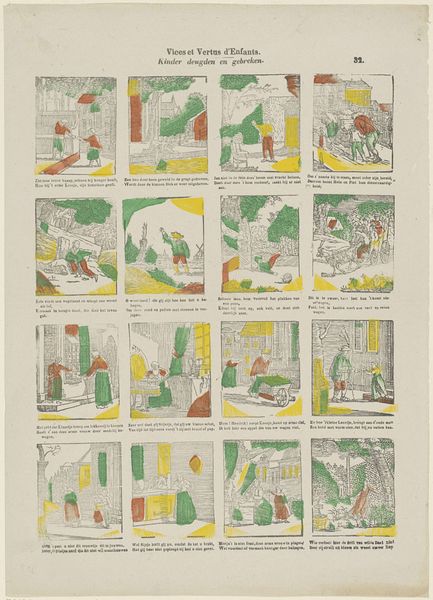

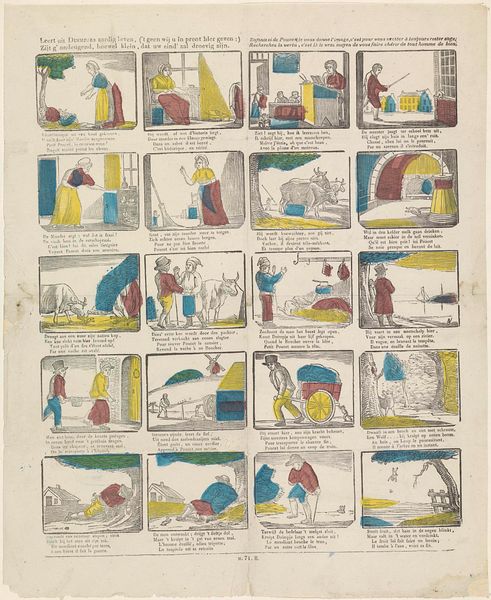

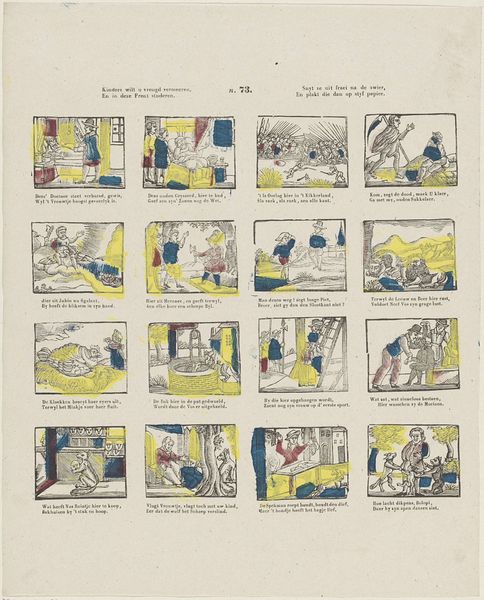

Curator: Philippus Jacobus Brepols, between 1800 and 1833, created this fascinating engraving print. It's housed here at the Rijksmuseum. The piece is called, and bear with me here, "Leer, jongheid, hoe de deugd, geprent in d'eerste jaren, / De mensch uit 't nedrig stof tot d'eersten stand doet varen / Apprenez, par ceci que la vertu conduit, / A la gloire aux honneurs, et que le bien s'en suit." Editor: Whoa, that title is quite a mouthful. My immediate impression is that it reminds me of those old-fashioned morality tales told through picture books, almost like a visual sermon about virtue and rising above one’s station. The print quality gives it such a historical feel, and yet, there’s something almost modern about the composition with all the tiny boxes...like a storyboard! Curator: Exactly! The piece uses a narrative approach common during the Romantic era, using a sequence of vignettes to tell a larger story. Each individual image seemingly depicts a stage in life and emphasizes upward mobility achieved through virtuous acts and behaviors. You get history-painting, genre-painting...the whole kit and caboodle. Editor: The theme of personal uplift is certainly intriguing considering the socio-political environment of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. I find myself wondering who the intended audience was for Brepols’ print? The emphasis on morality coupled with promises of success read as quite prescriptive, subtly reinforcing existing social hierarchies through the guise of personal empowerment. Were these prints targeted towards children? The burgeoning middle class? Or even used as tools for indoctrination within colonial contexts? Curator: Good question! The deliberate use of Dutch and French suggests an audience spanning social classes and perhaps geographic boundaries. It is also so reminiscent of the “penny dreadfuls” of Victorian England and all sorts of visual propagandizing with printed images, even earlier. Editor: It all makes one really question the relationship between art, social engineering, and power structures... it's really hard not to interpret such pieces outside of those frames. I leave with a slightly unnerving sense of how images become implicated in disseminating dominant narratives. Curator: Agreed. For me it sparks thoughts about how much of our own narratives, how much of our self-worth, are derived, even now, from the images we take in and internalize, consciously or not.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.