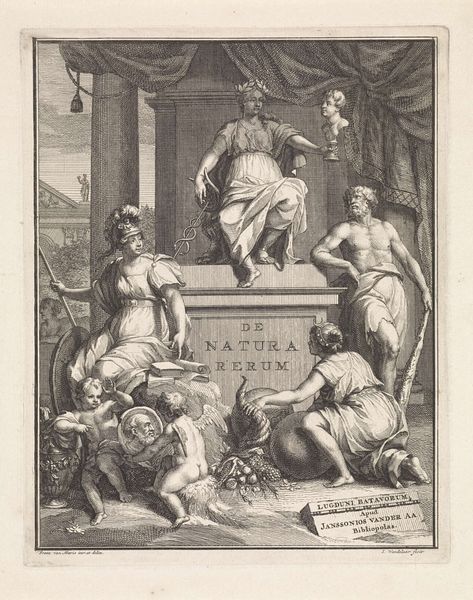

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 455 mm, width 270 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, titled "Hoop, Geloof en Liefde," which translates to "Hope, Faith, and Charity," dates from about 1717 to 1763, created by Pietro Monaco. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What catches your eye first? Editor: The dramatic contrast. The way light seems to struggle through, defining these figures so intensely. There’s an almost operatic feel, heightened by their very theatrical poses. Curator: Precisely! It's evocative of the Baroque era, where emotional intensity reigned. Each figure symbolizes one of the three theological virtues: Faith holding the cross, Hope grasping the anchor, and Charity, surrounded by children. What I find compelling is how these virtues are intertwined, almost dependent on each other for meaning. Editor: The positioning really reinforces that. Faith leans on the cross for support; Hope looks heavenward. Charity with those kids around her— a complex image there. Motherhood has never looked so severe to me! But what did the original viewers read in it at the time? Was Charity really idealized that way in art? Curator: It’s a question of context. Remember this image circulated as a print. Its didactic purpose meant something different in the bourgeois household than perhaps as monumental sculpture. Its presence encouraged a way of reading scripture. The virtue of the household was also a tool for the formation of social bodies. Editor: So, how does Monaco, a printmaker copying someone else, translate this high allegory for a mass audience? Curator: Notice the detail given to Charity’s children compared to the architectural frame? These were meant as familiar, comforting associations; that familial context probably resonated more clearly with viewers than intricate theology. Editor: Absolutely. And Faith looks resolute, not pained, holding high the crucifix in defiance of shadow. Curator: Symbolism within symbolism. It’s this visual layering that keeps such allegorical works endlessly fascinating to decode, isn't it? Editor: Indeed. And this little trip into 18th-century virtue has given me much to reflect on our present-day values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.