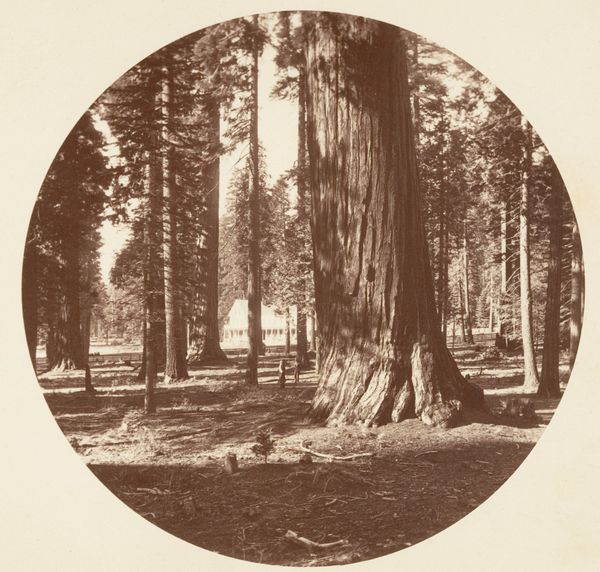

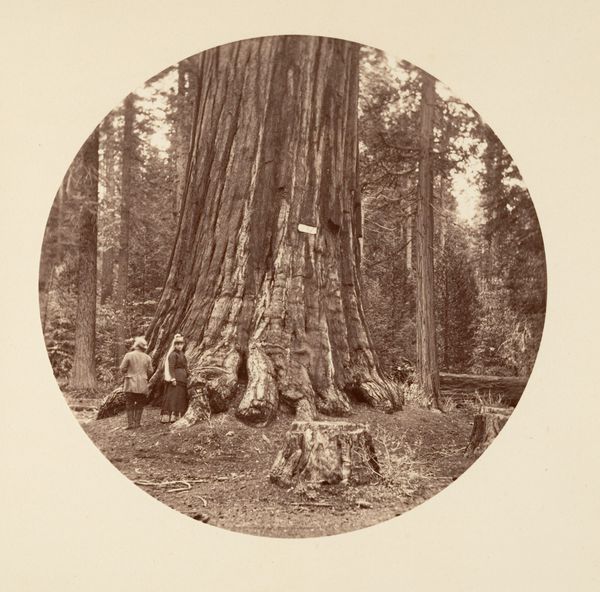

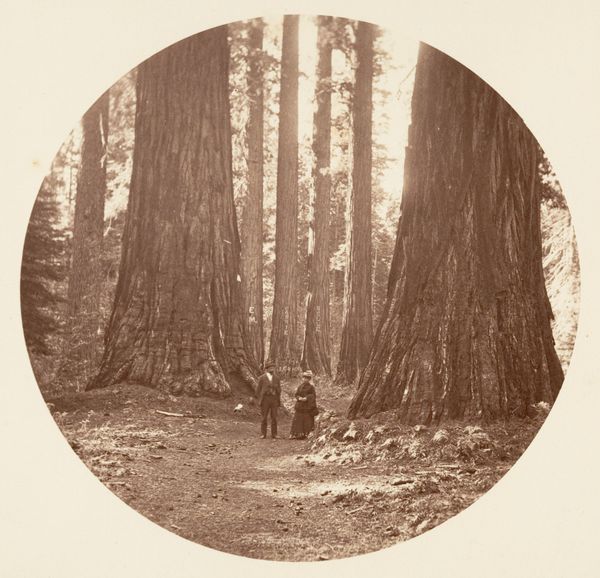

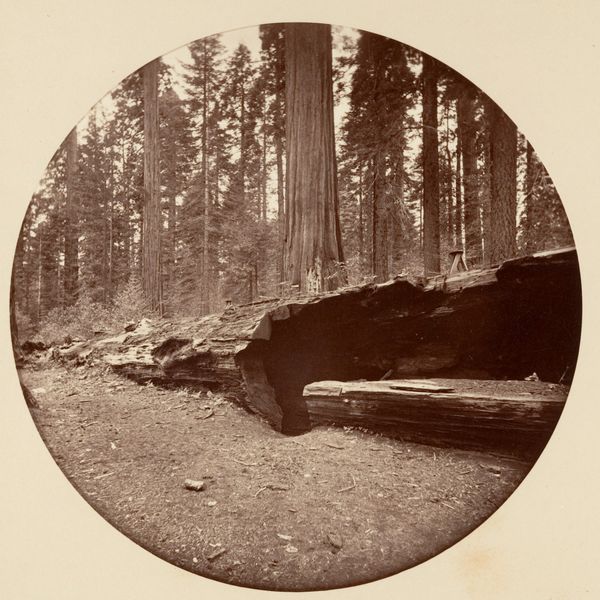

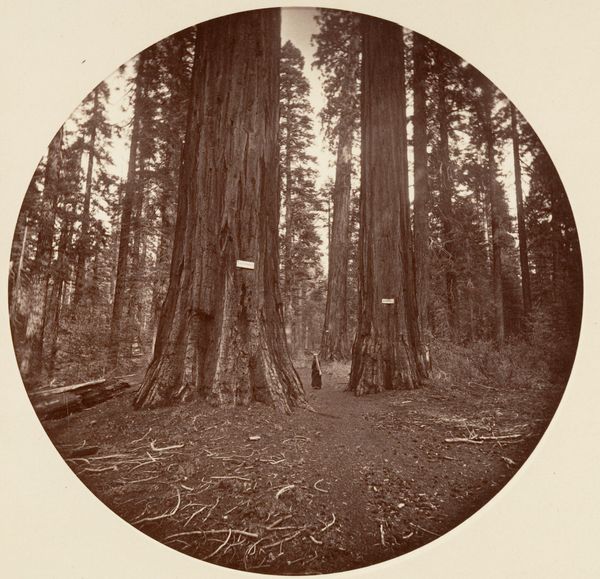

Dimensions: Image: 12.5 x 12.5 cm (4 15/16 x 4 15/16 in.), circular Album page: 24 x 25.1 cm (9 7/16 x 9 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Carleton Watkins' "W. C. Bryant - Calaveras Grove," likely captured between 1876 and 1880. The work is an albumen print photograph and is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s immediately striking, isn't it? Editor: Yes, I’m compelled by the contrast between the imposing, almost primordial trees and that... is that a building nestled amongst them? It’s odd how small the architecture seems compared to nature’s scale. Curator: The framing is key. Watkins deliberately placed the viewer between the monumental sequoias to emphasize the insignificance of human endeavor against the backdrop of nature. Note the classical framing— the large trees forming a proscenium to stage a vision of manifest destiny. Editor: Precisely, it makes one consider the labor involved in capturing such images. The work to set up in a difficult environment with cumbersome equipment—the tent, the glass plates, the chemicals—is enormous. It wasn't merely a snapshot but a constructed artifact, highlighting human interaction and the material constraints in photography. Curator: The light! Watkins masterfully captures it as it filters through the canopy. It's a study in tonal balance, isn't it? And the rounded edge of the print itself serves to soften the landscape, presenting an arcadian vista, seemingly untouched. The trees assume a almost divine stance, reaching upward to challenge conventional spatial order. Editor: Well, beyond its formal aesthetics, it is critical to remember the social and environmental ramifications of what we’re seeing: these images helped fuel the movement for national parks. Photography encouraged romantic appreciation—that led, crucially, to preservation. However, these sublime trees exist because of indigenous people's erasure. We must consider how natural wonder is a produced effect that’s often tethered to destructive colonial labor practices and systems of oppression. Curator: An important reminder, yes. Thinking about the legacy of the American West… One might even call it problematic—or more directly—the romantic sublime aesthetic as itself propaganda. It makes you think doesn’t it? Editor: Indeed. It highlights that nature is invariably touched by culture. That the trees stand tall as an example of humanity’s creative engagement, and disruptive modification, to the natural world, reminding us to understand both its formal brilliance and the processes that have shaped our experience of the world around us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.