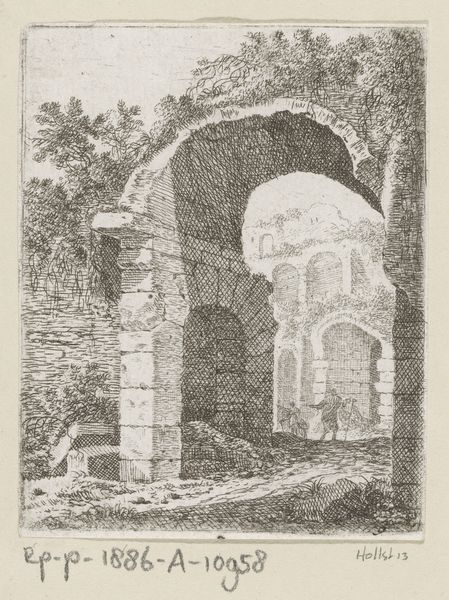

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

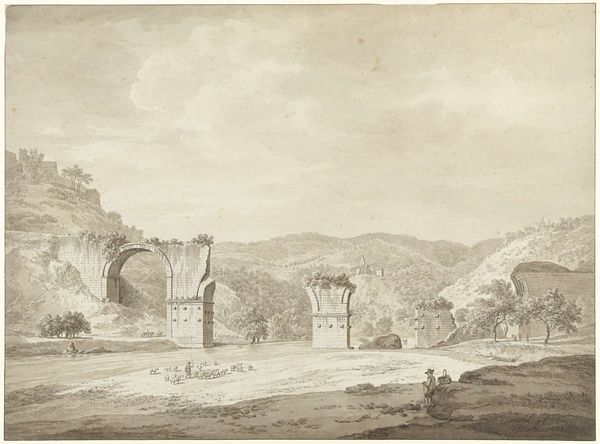

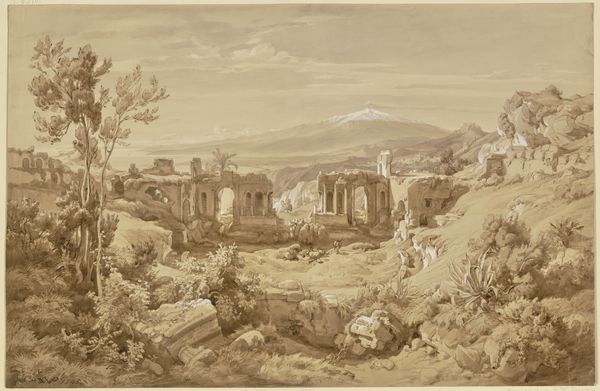

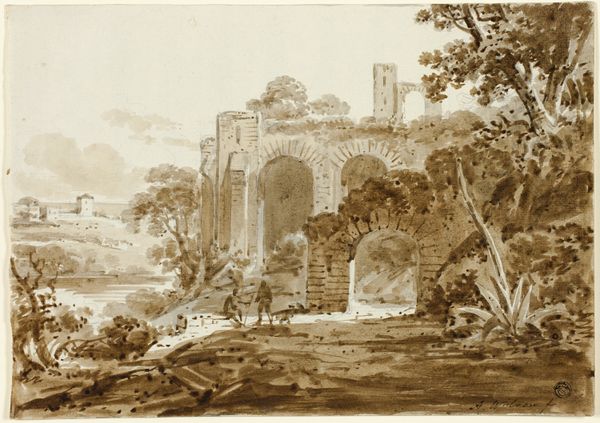

landscape

#

romanesque

#

geometric

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 203 mm (height) x 315 mm (width) (bladmaal), 150 mm (height) x 214 mm (width) (plademaal), 127 mm (height) x 186 mm (width) (billedmaal)

Curator: This etching, "Landskab" by J.F. Clemens, dating roughly between 1748 and 1831, offers a striking image. It’s currently held in the collection of the SMK, the Statens Museum for Kunst. What’s your immediate reaction to it? Editor: I'm immediately struck by the composition. There’s a sense of decay and the slow reclaiming of architecture by nature. The etched lines are so intricate; you can almost feel the texture of the crumbling stone. It also speaks to the labour involved in both the creation of the structure itself and its subsequent depiction by the artist. Curator: It certainly does. We see here ruins amidst nature, hinting at the passage of time, which speaks to broader historical narratives. Consider the role of landscapes in the Romanesque period and Clemens' historical context. His social and political environment would've heavily influenced his focus. Editor: Right, how does Clemens treat the materiality of the scene? Look at how the etching captures the different textures – the smooth water versus the rough stonework of the aqueduct. Also, what ink was used? Where was the paper sourced? These factors materially informed the artwork and its availability for consumption by the contemporary art market. Curator: Precisely, and these prints had a purpose beyond simple aesthetics. The availability and distribution would disseminate specific images and ideas linked to antiquity and landscape art as well as cultural notions around ruins and our place in the world. Think about what locations he depicts. Do those selections promote social ideologies? Editor: Very interesting question. Perhaps that's precisely what this aqueduct, these ancient technologies and engineering feats overgrown with nature, signal. Consumption and decay over time. The choice of etching too; this would mean this piece was far more available to a wider audience, in turn suggesting it was crafted as an inherently more accessible political and social piece of work. Curator: Reflecting upon our discussion, I see this not merely as a representation of a decaying aqueduct. Rather, it’s a glimpse into 18th century ideologies around progress and historical cycles that are reflected and shaped by the material circumstances in which Clemens operated. Editor: And I find myself captivated by the interplay of human labor and natural reclamation, the availability of this artwork to mass consumption, all elegantly preserved in the etched lines—a potent statement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.