photography

#

16_19th-century

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

photography

#

geometric

#

19th century

#

cityscape

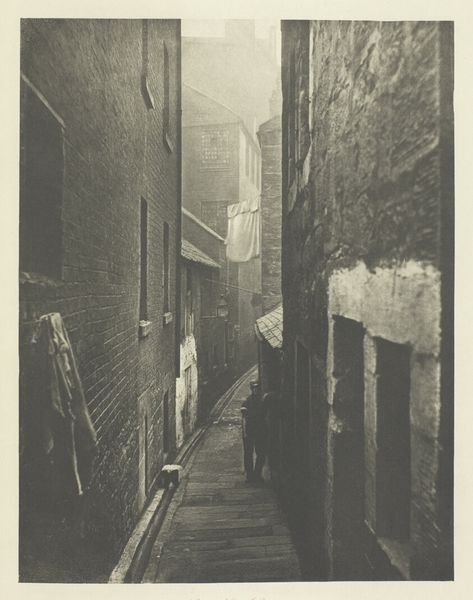

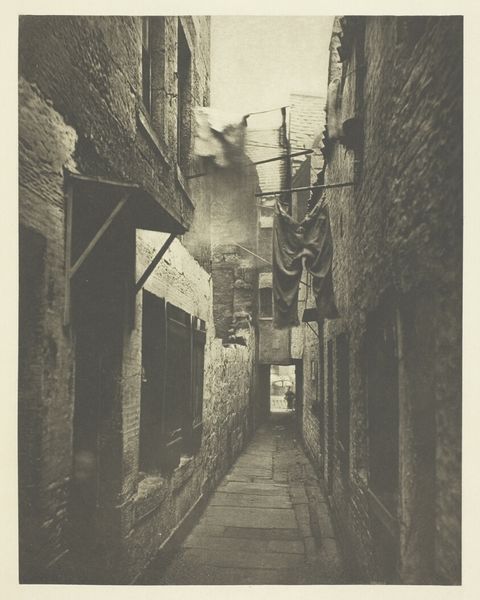

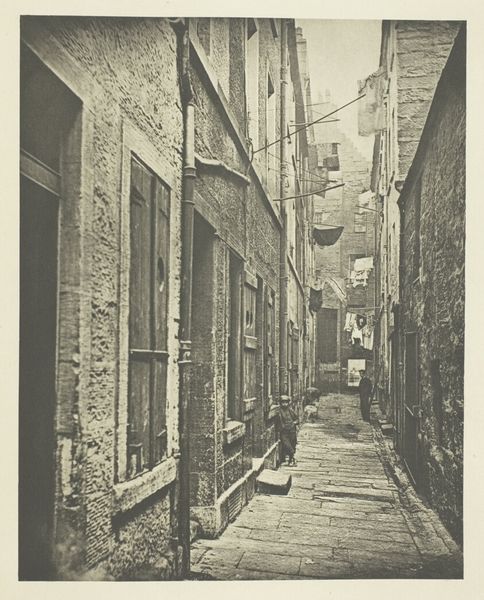

Dimensions: 17.2 × 22.1 cm (image); 27.9 × 37.6 cm (paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

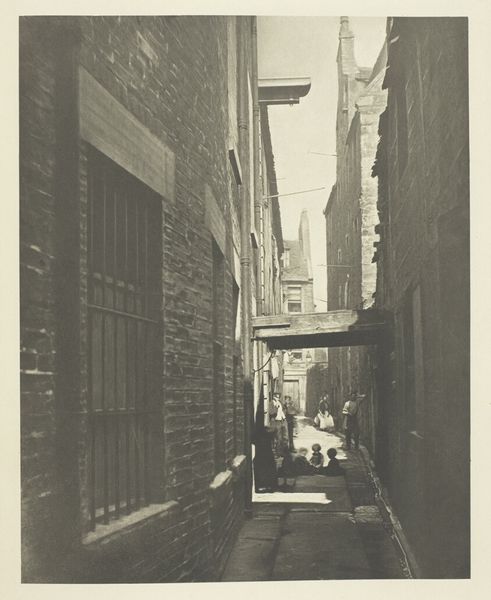

Editor: So, this is James Craig Annan's "Close No. 29 Bridgegate," a photogravure from 1897. The overwhelming use of brick makes it look heavy and almost oppressive. What's your take on it? Curator: I'm drawn to the materiality itself. Think about the social implications of brick—cheap, readily available, mass-produced building material reflecting industrialization and urbanization at the turn of the century. This photogravure isn’t just a cityscape; it’s a record of the labour embedded in each brick, a testament to the physical act of building this close. Editor: That’s a fascinating point! I hadn’t considered the labor involved. So, the medium and material tell a story? Curator: Precisely! Annan's choice of photogravure is key. He's not merely capturing an image. He's manipulating a process that requires considerable skill and specialized equipment to produce a print that mimics the tonal subtleties of painting. It’s a negotiation between the mechanization of photography and the handcraft of printmaking. Does that push against the boundaries of what constitutes "art," you think? Editor: I suppose it does. High art meeting the more quotidian reality, the working-class realities… Curator: Exactly! And, this image then enters into a cycle of consumption, sold as art, hung on walls. What are we consuming when we acquire an image like this? Editor: We’re buying a piece of history, not just aesthetically, but a physical piece, in a way, reflective of social dynamics and industrial production. I'll never look at a photogravure the same way again! Curator: That's the beauty of considering materiality – it shifts our understanding entirely! It reframes the aesthetic experience as a direct consequence of a larger social, industrial, and economic framework.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.