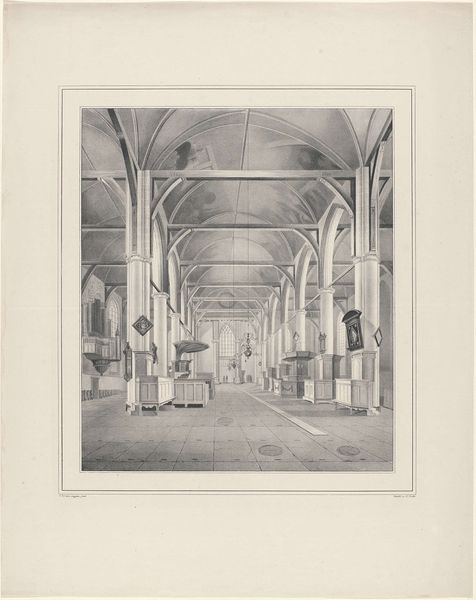

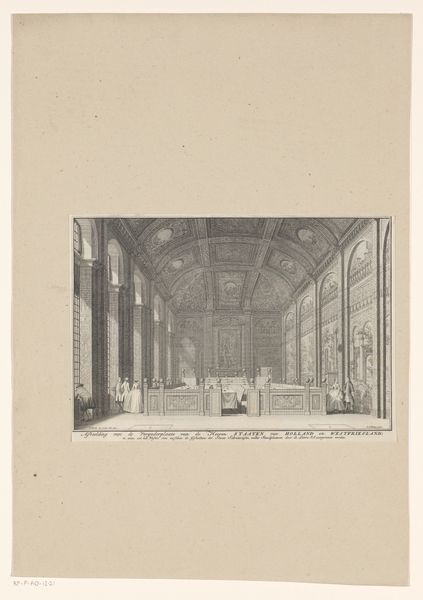

De kerk van Jaffanapatnam gelegen op Sri Lanka, door Steiger 1890 - 1910

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 221 mm, width 273 mm, height 325 mm, width 438 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The atmosphere is thick with the weight of history; it’s silent yet resonant with voices, if that makes sense. Editor: It certainly does. Looking at this work titled "De kerk van Jaffanapatnam gelegen op Sri Lanka, door Steiger" (The Church of Jaffanapatnam located in Sri Lanka, by Steiger), dating back to sometime between 1890 and 1910, one immediately notices the emphasis on structural rendering— the way pencil and ink are meticulously applied to describe form. Curator: Beyond the visual impact, it is important to contextualize it. Churches were a nexus of power, not just spiritual, but also political and colonial. To depict a church in Jaffna during that period requires reckoning with layers of identity, imposition, and possible resistance. The materials tell a clear story about production, this isn't painting but accessible mark-making. Editor: Indeed, let's not forget how drawings served practical functions: documenting colonial architecture. The artist employs paper, pencil, and ink not merely for aesthetic purposes but as instruments of recording—mapping and ultimately appropriating space. Curator: So, while the technical execution, with its precision and detail, can appear rather straightforward, what stories remain concealed under these structural lines? What about those indigenous populations affected by this building and its doctrines? We can read the structure of the image itself, looking into negative spaces, for those untold stories, perhaps even gestures of subversion or adaptation. Editor: I agree it's imperative that we question the image's creation. Who commissioned it, and for what reason? Examining the socio-economic conditions in which it came into being brings to the forefront labor practices and power dynamics. Who constructed this church, using which materials and under what terms? These are not mere aesthetic inquiries but questions concerning lived experiences. The artist's chosen means, this reliance on rather portable techniques and cheaper materials might speak to both the nature of this type of colonial work, and potentially the agency involved in choosing accessible material for creation. Curator: Precisely. Looking at Steiger’s work provokes necessary reflections. How do seemingly benign depictions contribute to wider ideologies and unequal power structures? The building's symbolism becomes more significant when positioned inside these geopolitical and social narratives. Editor: This discussion helps bring us a comprehensive engagement that integrates the formal qualities with its production and deeper historical significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.