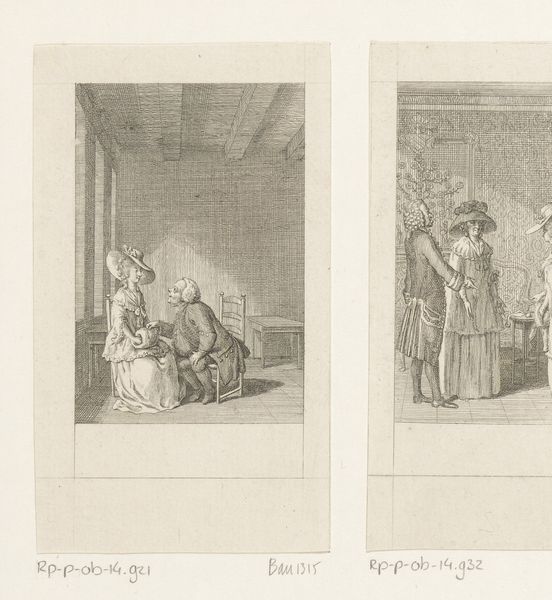

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving from 1789 by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, titled "Peter the Great Kisses the Condemned Woman," I’m immediately struck by its stark portrayal of power and vulnerability. Editor: Yes, that's my immediate impression too. I find myself drawn to the textures, especially the hatched lines used to depict the clothing and create tonal variations. It's interesting how the medium itself, this print, contributes to the story’s solemn feeling. The labor in creating this—the etching process, the paper it's printed on—all these materials underline the gravity of the depicted scene. Curator: Indeed. Consider the socio-political climate in which this image was made. The late 18th century witnessed a surge in interest in representing historical narratives and moral lessons. Prints like these would have circulated widely, shaping public perceptions of rulers like Peter the Great. What purpose did prints like this serve for public audiences? Editor: Well, beyond pure documentation or illustration, it looks like Chodowiecki engaged the contemporary print market by reproducing historical anecdotes as moralizing images, or a cautionary tale to promote social control. Notice the precise lines used for rendering figures versus the relatively quick crosshatching to show their garb and the other material features of the artwork. Curator: Right, and we need to consider the institutional context as well. Pieces like this were often commissioned or created for specific patrons, playing a role in the patronage system of the time. The Rijksmuseum as the owner influences how this artwork is seen today, giving it new relevance in art and social historical discourse. Editor: The distribution of such a print through various channels — from individual sales to bound collections—affected who encountered it and what social significance they gleaned from it. I wonder, what does this engraving tells us about the means of production of visual content in the late 18th century? Curator: This reminds us that art doesn't exist in a vacuum. It’s embedded in social networks, economic realities, and political agendas. It forces us to think about art's social responsibility, and the historical power that leaders exert. Editor: Precisely. Analyzing the processes involved— from artistic choices to distribution methods—allows us to connect artistic representation to social experience, while questioning the very notion of "high art." We gain deeper insight into a particular social-cultural historical juncture when examining materials used and methods applied in art production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.