print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

narrative-art

# print

#

impressionism

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

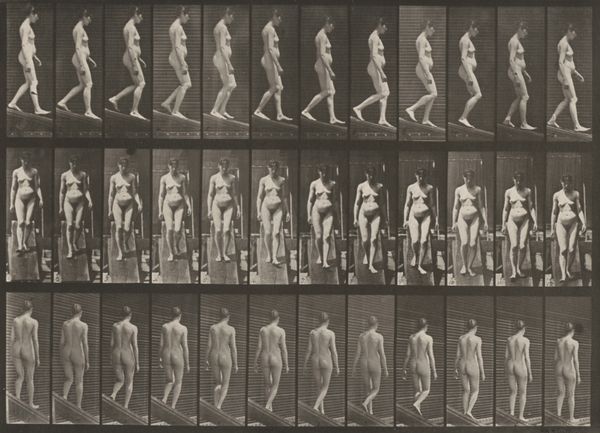

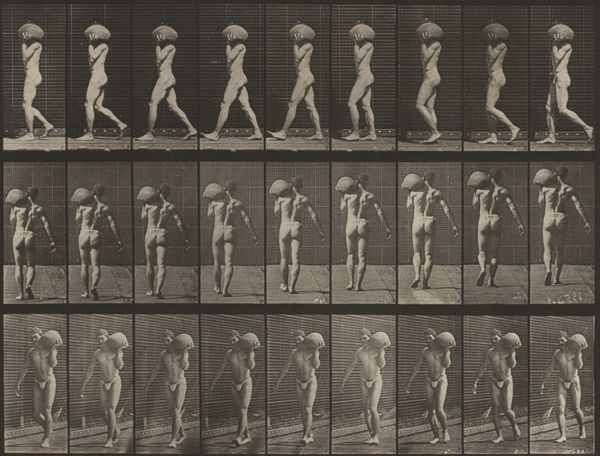

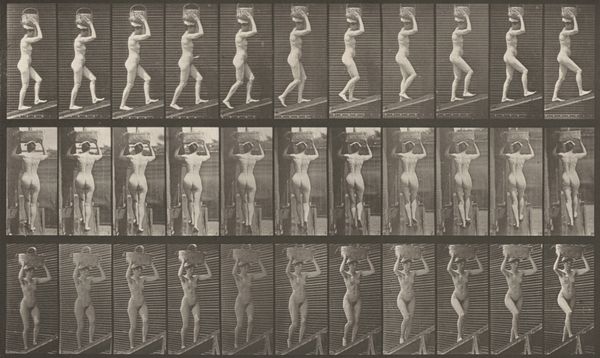

Dimensions: image: 22.2 × 34.7 cm (8 3/4 × 13 11/16 in.) sheet: 40.8 × 61.1 cm (16 1/16 × 24 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

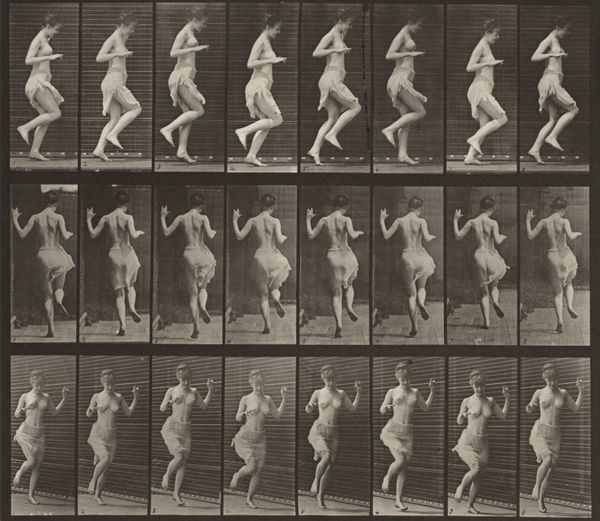

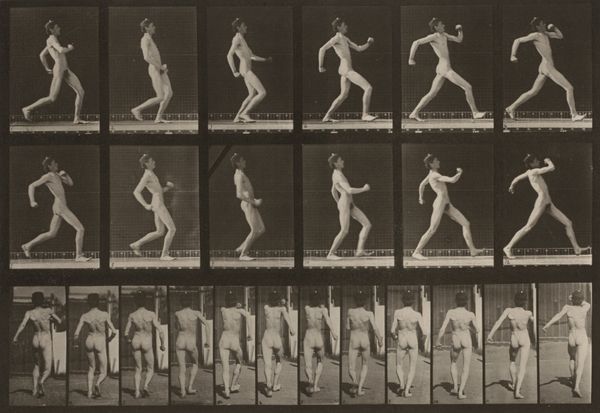

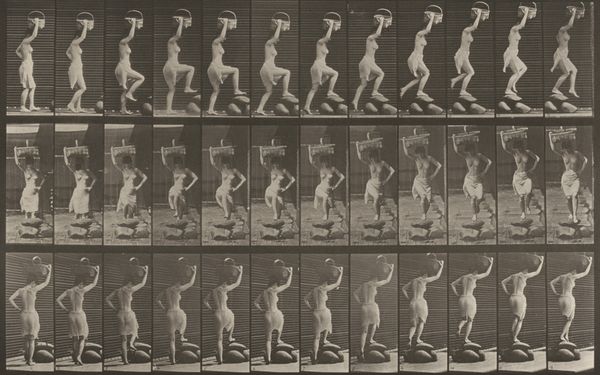

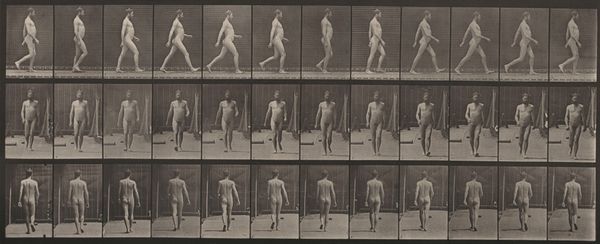

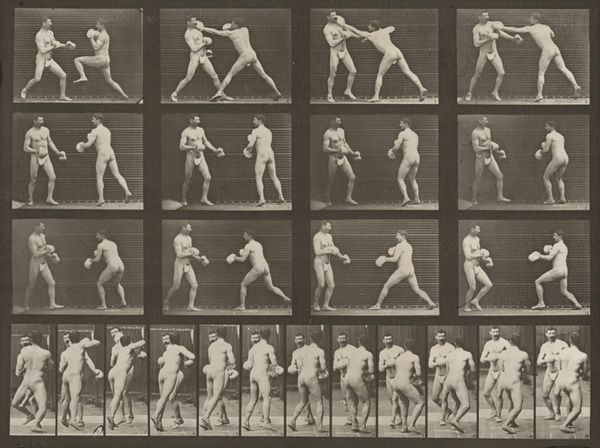

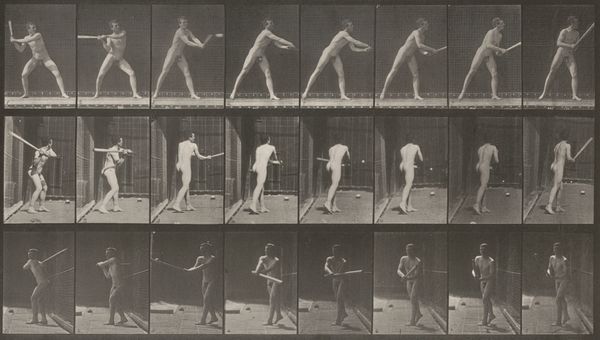

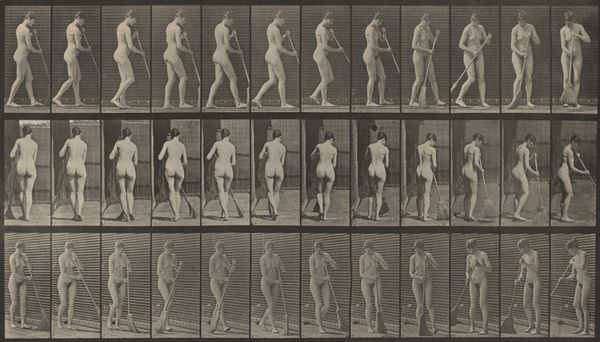

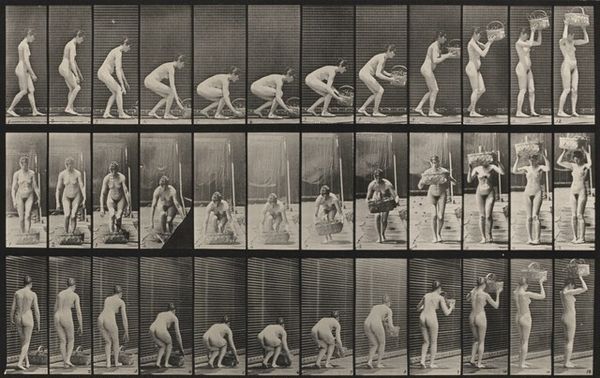

Curator: Eadweard Muybridge's "Plate Number 12. Walking," created in 1887, offers a fascinating glimpse into the early days of motion study through photography. This gelatin silver print is one in a series where Muybridge captured incremental movements to analyze locomotion. Editor: My immediate impression is of scientific curiosity rendered almost absurd. The starkness, the rigid grid, and the unclothed figure highlight a detached quest for knowledge, evoking Victorian-era fixations with classification. It’s cold, precise, and a little…invasive. Curator: Precisely. The starkness you note wasn't just aesthetic; Muybridge sought empirical data. His work, commissioned initially to settle a bet about whether all four hooves of a horse left the ground during a gallop, evolved into a broader scientific investigation. This plate isolates the human form to dissect a simple act: walking. Editor: Yes, but that isolation is key, isn’t it? By stripping away context—clothing, environment, identity—the body becomes an object of study, reinforcing a hierarchical gaze. It also foreshadows later dehumanizing applications of visual surveillance. How much does Muybridge consciously explore power, gender, or race here? Curator: Well, the explicit goal was not about social commentary but rigorous documentation. The scientific and academic circles were deeply engaged in quantifying and categorizing all aspects of the natural world at the time, humanity included, sometimes reflecting unfortunate racial or gender biases implicitly in their scientific endeavors. But that's part of why it continues to hold value as a point of reflection on societal priorities through the lens of history. Editor: True, seeing it within the scientific climate of its time adds nuance. It allows us to interrogate not just the image itself, but the societal values it reveals and reinforces. We can begin to see the walking man within these parameters, walking through both history and a minefield of social constructs. Curator: Right, it compels a critical dialogue around the scientific gaze and what it chooses to reveal—or obscure. Editor: Exactly. It's not enough to simply observe the movement; we need to ask: who gets to observe, who is observed, and what biases shape that act of observation? That walking man’s historical footsteps take us further than first assumed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.