#

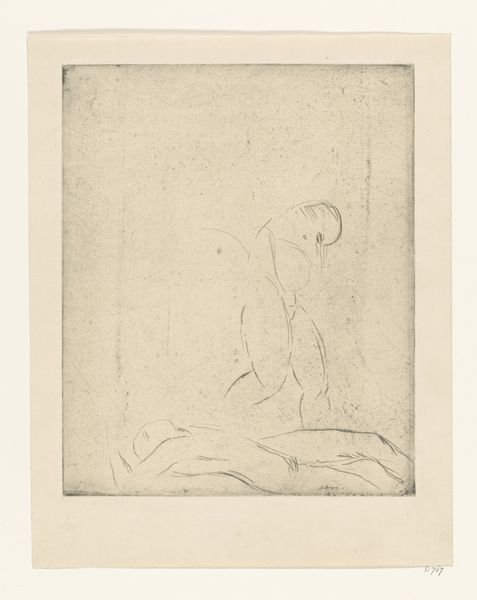

photo of handprinted image

#

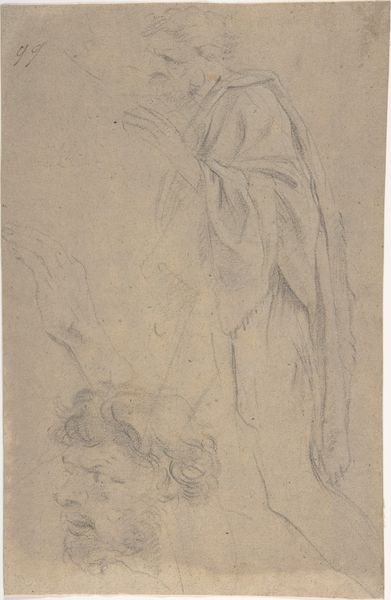

toned paper

#

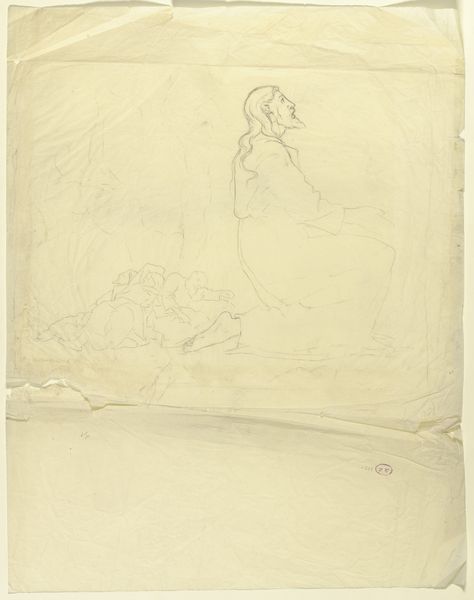

pencil sketch

#

white palette

#

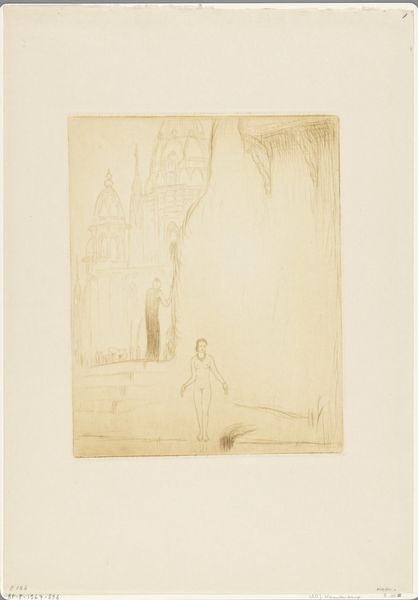

etching

#

tea stained

#

watercolour illustration

#

tonal art

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 247 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Wijnand Otto Jan Nieuwenkamp's "Bathing Girls on the Banks of the Ganges in Benares," possibly from 1917. The subdued tones and sketchy lines give it an unfinished feel, almost like a memory. What strikes you most about this work? Curator: I immediately focus on the "handprinted image" as it is referred to in its metadata. The technique of etching and possible tea-staining on toned paper points towards an important tension, one that blurs the lines between fine art and the everyday practices of craft. Nieuwenkamp chose to highlight the *process* itself. Do you see any potential meaning arising from this emphasis on process? Editor: I guess focusing on process over pristine product shifts our attention to the labor involved, maybe challenging the romantic idea of the lone artist effortlessly creating beauty? Curator: Precisely! Consider also the social context. Nieuwenkamp, a Western artist, depicts a scene in Benares. The material choices – etching, staining – carry a colonial weight. It wasn't mass produced through industrial printing. What does the deliberate choice of these ‘hand’ methods convey to you? Is it romanticizing “exoticism”, or engaging in a material critique? Editor: It's complex. Maybe the hand-printing suggests a slower, more intimate engagement with the subject, attempting to counter the speed and detachment often associated with colonialism? But could it also be a form of appropriation, where he's borrowing from another culture to elevate his own art? Curator: Exactly. Think about the availability and distribution of the art work too. Limited numbers due to the time constraints around printing equals higher worth on a commodified art market. His labor becomes part of the final artwork’s cost, making it inaccessible. What I find interesting here, however, is that he makes this colonial dynamic more visible, more tangible through the very *stuff* of his art. Editor: That makes me look at it in a new light. I was so focused on the image itself, but you're right, the materials and process are just as important, especially when considering its historical context. Curator: Absolutely, and hopefully, we also realize our subjective perspective toward artistic productions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.