drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 252 mm, width 348 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

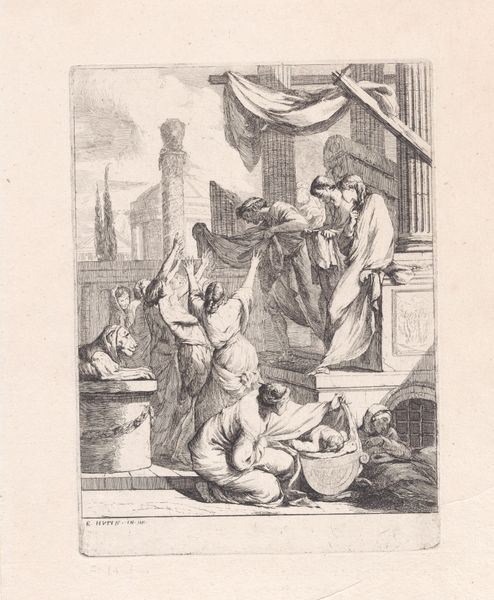

Curator: This ink drawing, "The Recognition of Achilles," comes to us from the hand of Jan Weenix, dating somewhere between 1650 and 1719. It depicts a classic mythological scene, rendered with swift, expressive lines. Editor: It's got a frenetic energy, doesn't it? All the figures are caught mid-gesture, everything in motion. It's almost chaotic, even with the stately architecture in the background. Is that the contrast that Weenix seeks? Curator: I think so. He's playing with the theatricality of the scene. You've got the grandeur of the palace and the drama of the moment—Achilles, disguised as a woman, being revealed. And look at how the ink washes emphasize the fabric, the textures of their clothes. It suggests a world of luxury, woven textiles, costly materials fueling all that posturing. Editor: The handling of the ink speaks to the practicality of quick preparatory sketches; no doubt there were multiple workshops using similar processes, repeating the stories over and over to keep pace with public appetite. The efficiency of the line work gets it down on paper fast. But consider all that ink, too. Trade routes bringing it to workshops, apprentices grinding pigments… there is real labor here, transforming materials from across the globe. It reminds me of those booming Baroque industries and the power dynamics they upheld. Curator: Precisely. The drawing invites us to think of the artist in the context of production, with so many other hands and so many other stories—not simply of mythology, but of craftsmanship and ingenuity, from the preparation of paper to its eventual sale in the public markets of the Netherlands. I suppose it's also why Weenix, as an artist who understood and even participated in these conditions, looked so acutely to history painting as the artform through which to imagine all that worldmaking in the first place. Editor: Ultimately, the drawing does more than illustrate a well-known tale. It highlights how stories were actively being remade for the social aspirations of a Dutch Golden Age through art and art markets. Curator: Right, making those ancient heroes speak to a very present, and very material reality. And with this drawing we have our own chance, hundreds of years later, to give it our own reading. Editor: Exactly. And the lines still hold—holding this vision together. Pretty amazing, huh?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.