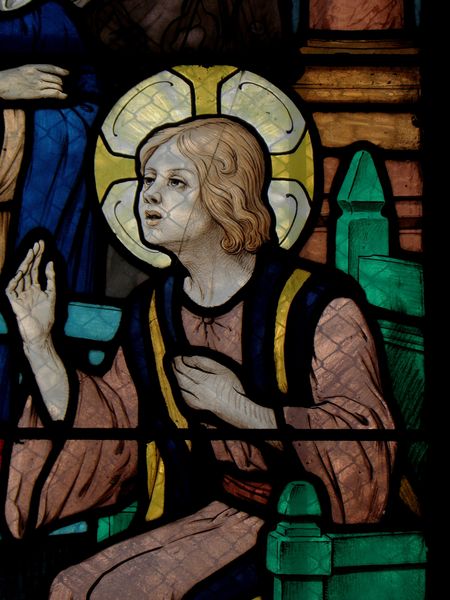

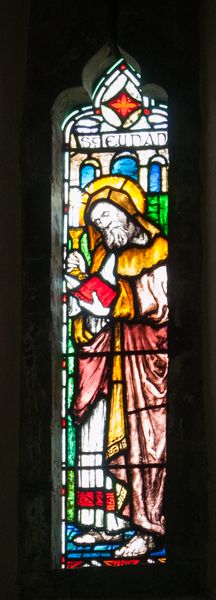

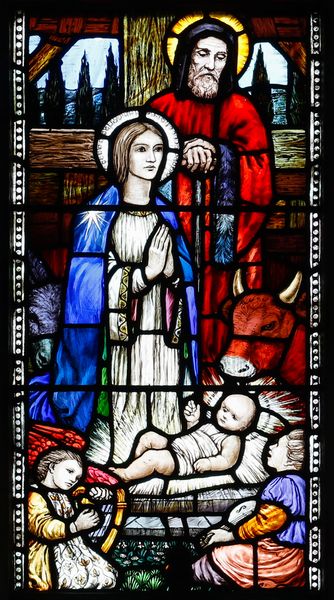

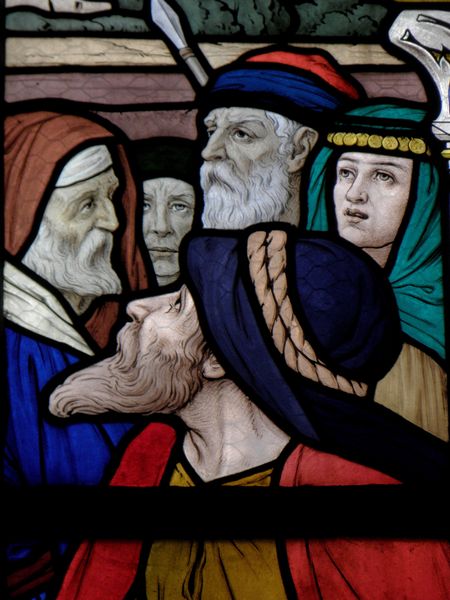

Jesus and the Samaritan woman. Eglise Saint-Sulpice de Fougères (detail) 1919

0:00

0:00

painting, public-art, glass, mural

#

public art

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

public-art

#

figuration

#

mural art

#

glass

#

tile art

#

history-painting

#

mural

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: This stained glass detail is by Ludovic Alleaume, completed in 1919, depicting "Jesus and the Samaritan woman" at the Église Saint-Sulpice de Fougères. The pale luminescence radiating from Jesus immediately captures attention. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Well, it’s clearly striking—the lead lines holding the glass together create this almost brutal geometric scaffolding. It clashes strangely with the subject, almost imprisoning it. The materials feel heavy. Curator: Absolutely. The leadlines do serve a practical structural function, but here they amplify the narrative. Consider how Alleaume has employed medieval archetypes; this scene, rich in symbolic meaning, focuses on Jesus’s spiritual authority, even over established social norms. Editor: So, even in the early 20th century, artists were returning to pre-industrial forms and subjects. What did engagement of artists like Alleaume mean at the time it was made in the wake of a conflict that relied so completely on modern manufacturing? Curator: That’s insightful. This glass functions as more than simple decoration; it represents faith in the face of modernity’s disruptive forces. The return to figuration connects the viewers to historical and spiritual values. Notice the subtle palette-- blues, reds, pale ambers – it evokes serenity. Editor: Yes, but it's a restrained palette; almost muted compared to, say, Chartres. Look closely— the texture in Christ’s robe almost resembles hammered metal. This panel then isn’t simply about piety, but it’s very self-aware about its process. Curator: Indeed. Alleaume, masterfully using the medium's constraints to express both divine presence and human connection. We've witnessed the enduring power of symbolic visuality and the tangible impact of its construction. Editor: Ultimately it showcases the enduring nature of artistic innovation—both through symbol and stuff.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.