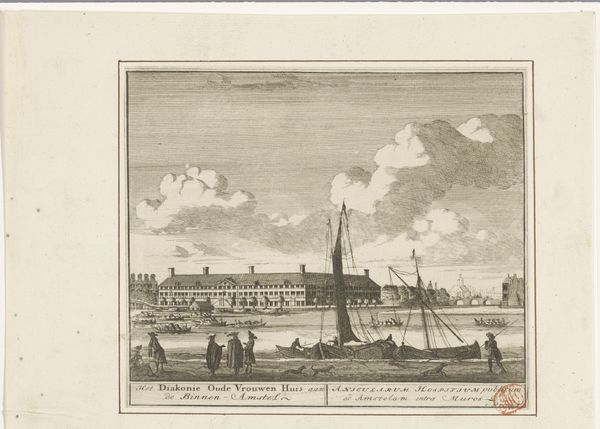

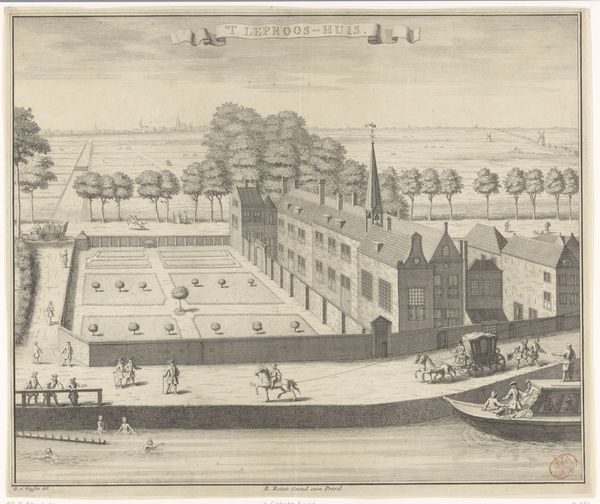

Gezicht op het Diaconie Oude Vrouwenhuis of Amstelhof te Amsterdam c. 1695 - 1700

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 203 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at the precision of this engraving, isn't it remarkable? The artwork is titled "Gezicht op het Diaconie Oude Vrouwenhuis of Amstelhof te Amsterdam," dating from around 1695 to 1700, its author remaining anonymous. Editor: There's something so orderly about this scene; yet also cold, would you agree? The composition is rigorously balanced, but somehow sterile. It almost reminds me of a panopticon. Curator: Precisely! Think about the period and context of the Dutch Golden Age. This aesthetic resonated with the burgeoning mercantile class, embodying their values. This image depicts what was formerly a charitable institution or almshouse for elderly women, the "Diaconie Oude Vrouwenhuis," reflected on the Amstel river. Editor: Which reads very much as the symbolic order of this era, yes, with its rigid class hierarchies. Note the perspective: The institution sits on the bank, with the commoners, literally, sailing beneath it, going about their daily toils, reinforcing their subordinate positions within the cityscape's frame. I wonder who commissioned this work. Curator: Well, its function would probably have been for a burgher of the city to present or represent to themselves their place and authority within the growing city. Its symbolic order relies upon that position. Editor: Symbolically then, who are those women within its walls? Surely not simply beneficiaries of its namesake? The uniformity that this artistic mode is deployed in to depict also brings to mind the similar constraints imposed onto those same women within the system? Curator: Indeed! Architecture carries symbolic weight, but in this print, there’s also an undeniable social aspect embedded within that. Look closer: It may highlight a commitment to care, to social responsibility, and in some ways even celebrates the power and efficiency of social management. Editor: In the Age of Reason, naturally; yet one wonders how this "social care" intersected with gender and class. I imagine it also helped control behavior. And the etching reminds me how representations shape the social imaginary and, indeed, social action. Curator: Yes. When we read such prints through these visual shorthands, as you describe, this anonymous work, becomes something of a historical proxy for this order. Editor: Exactly, a reminder that even depictions of charity can be potent sites of social and ideological power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.