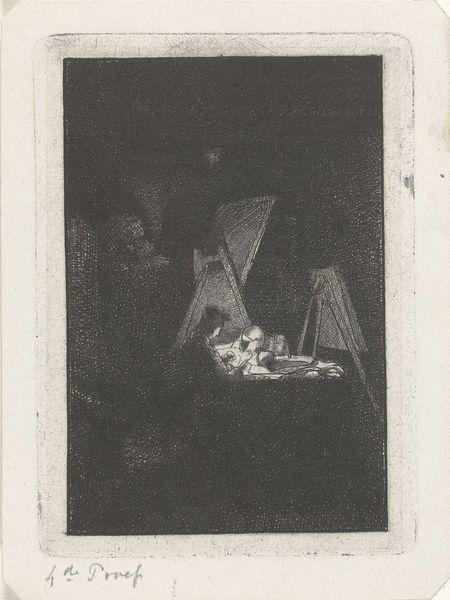

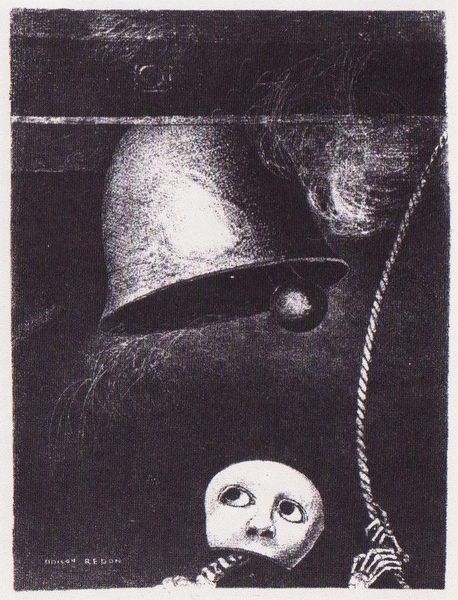

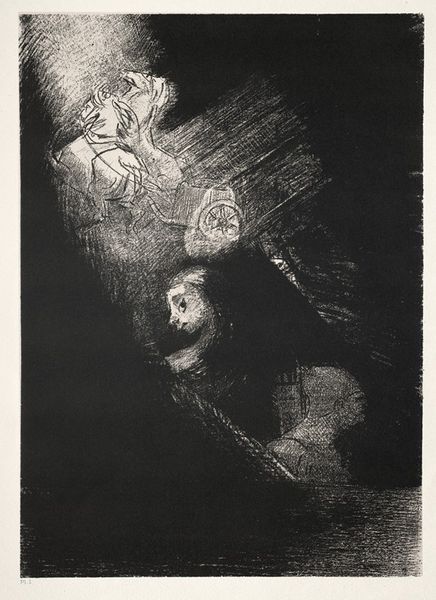

The Breath which Leads All Creatures is also in the Spheres 1882

0:00

0:00

drawing, charcoal, pastel

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

symbolism

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

pastel

Dimensions: 27.3 x 20.9 cm

Copyright: Public domain

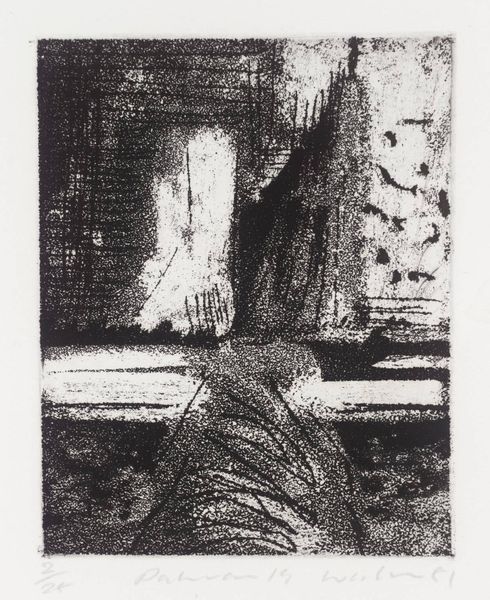

Curator: Stepping into the realm of dreams, we encounter Odilon Redon's charcoal and pastel drawing from 1882, titled "The Breath which Leads All Creatures is also in the Spheres," currently residing at LACMA. What's your first take? Editor: There's an immediate unsettling quality, the stark contrast, the nebulous shapes encroaching upon the human figure… It feels like peering into a very private, and somewhat disturbed, consciousness. Curator: Absolutely. Redon, deeply entrenched in the Symbolist movement, sought to visually articulate the intangible aspects of the human experience—dreams, the subconscious. Notice how the spheres crowd around the figure; these disembodied heads are common motifs, laden with a strange psychological weight that directly references social anxieties regarding industrial advancement at the time. Editor: Right, it seems as though the choice of charcoal really emphasizes that sense of weight. I’m interested in the way Redon manipulates the charcoal; you can really sense his physical involvement. Was the artist aiming to subvert painting's status in favor of the accessibility associated with drawing materials and their direct relationship to labor? Curator: Precisely. Drawing granted him a level of immediacy and freedom, enabling an efficient artistic response to academic constraints. More broadly, Redon challenged institutional assumptions about what was considered worthy subject matter, and his choice of medium and allegorical, somewhat anti-capitalistic motifs certainly reflect that sentiment. Editor: The more I look at this drawing, the more I admire the textural complexity achieved with what appear to be rather simple materials. He makes a political point through abstraction and material modesty; it’s as though the very act of making resists a particular kind of market consumption. Curator: I agree. Redon rejected naturalism, choosing to pursue what he called "the logic of the visible toward the invisible.” "The Breath..." is a poignant example. The dreamlike and spiritual quality that pervades much of his production aligns him with late 19th century debates concerning artistic and religious freedoms. Editor: A provocative exploration of mind and matter, indeed. I keep being drawn back to how those orbs—those looming heads—were rendered to convey such presence through such minimal means, but how else to reflect the intangible in something so corporeal? Curator: And isn’t that exactly Redon’s enduring allure; to create works steeped in symbolism that encourage introspection to such a wide audience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.