#

abstract expressionism

#

abstract painting

#

possibly oil pastel

#

oil painting

#

fluid art

#

acrylic on canvas

#

underpainting

#

paint stroke

#

painting painterly

#

expressionist

Copyright: Public domain

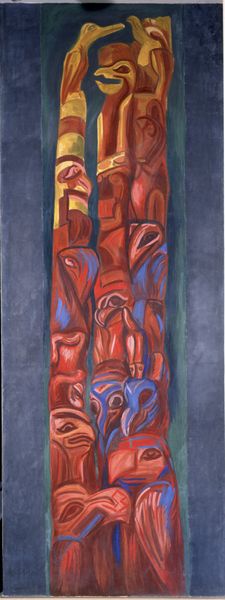

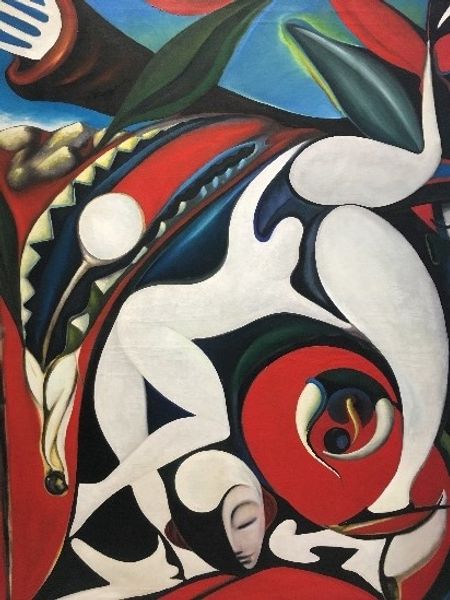

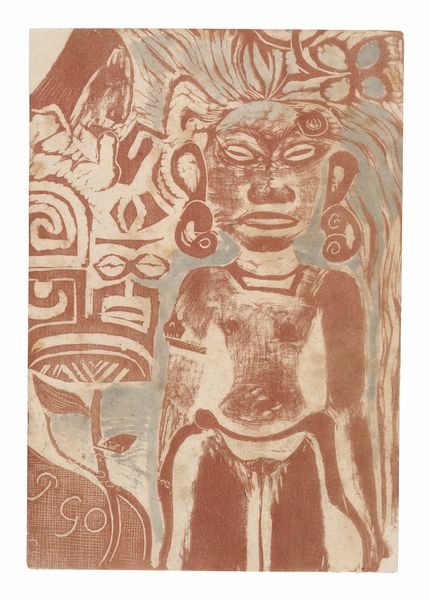

Curator: The first thing that strikes me is the colour. The blues and reds pop against that dark background, imbuing this panel with quite a sense of urgency. Editor: Indeed. The artist is José Clemente Orozco, and this is Panel 9 from his “The Epic of American Civilization” mural cycle, specifically the "Totem Poles" segment painted in 1934. It's a powerful fresco, created within a context of deep social and political change. Curator: "Totem Poles"—the title itself sets up immediate expectations and cultural connotations. The stylized figures evoke ideas of ancestry, spiritual guidance, and storytelling etched in wood, but recast here through the lens of modern painting. I sense both homage and interrogation. Editor: Orozco’s use of the totem pole image is particularly interesting, given its complicated role. In many Native cultures, totem poles function as historical markers, displaying crests, stories, and memorial figures, and they often represented social standing. But here, I believe he’s engaging with a more broadly conceived "American civilization." The layering of figures feels… volatile. Curator: I agree, there is that sense of impending tension. Consider how the various figures are stacked, intertwined. The artist clearly aims to illustrate both individual and collective human experience. You see strength, but also vulnerability and potential conflict. The iconographical implications are clear in how he merges symbolic heritage with Expressionistic styles. Editor: And he did so within a very specific space and time. Orozco painted these frescoes at Dartmouth College during the interwar period. It forces us to ask what vision of “civilization” he was projecting for this particular audience in 1934. Curator: A civilization on the brink? Absolutely. I also feel a strong pull to those colours again. Perhaps their vibrancy serves not only to highlight forms, but equally to jolt viewers into confronting the difficult questions of social responsibility and change. Editor: This panel offers so much layered symbolism—political statements blended with Indigenous and pre-Columbian signifiers—within the complex, troubled socio-cultural milieu of 1930s America. Curator: Seeing the composition, you begin to realize Orozco provides us with more questions than answers. It encourages us to reflect upon both history and how images become symbols that inform history. Editor: And in doing so, hopefully to encourage each one of us to shape its future direction for the better.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.