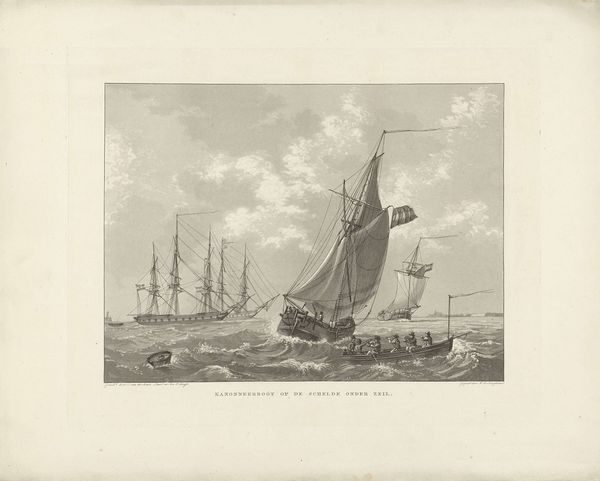

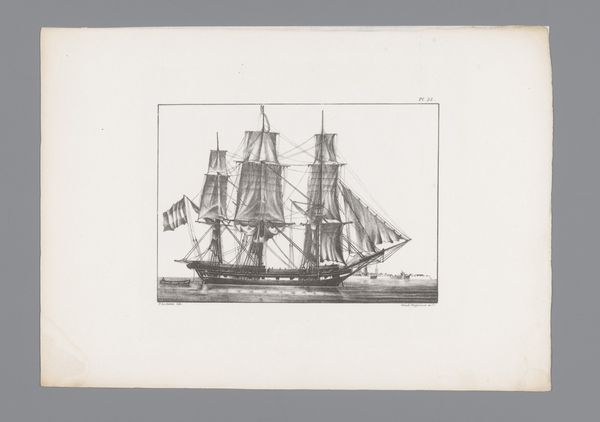

Napoleons lichaam wordt overgebracht op een stoomschip bij Cherbourg. 1840 - 1841

0:00

0:00

jeanbaptistearnout

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 308 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jean-Baptiste Arnout's engraving, "Napoleon's body is transferred to a steamer at Cherbourg," created between 1840 and 1841. It’s a bustling scene, but there's also a solemn quality to it. How do you interpret this work? Curator: This print serves as a fascinating window into 19th-century France and its complex relationship with its recent past. Think about what Napoleon represented: revolution, empire, and then defeat. Consider this image as more than a simple depiction of a historical event; it is a political statement. Who was this print created for and why? Editor: Well, considering the date, it's a bit after Napoleon's death, so I’d guess it's for a French audience reflecting on his legacy. Curator: Exactly. But was this about simple nostalgia? Or about something more? The 'transfer' of his body back to France speaks volumes. This was after the Bourbon restoration, after the July Revolution. The return of Napoleon's body becomes a symbolic act laden with questions of national identity, power, and memory. Can we ignore how such displays were traditionally carefully staged performances of sovereignty and nationalism? Editor: So it's about controlling the narrative? Shaping how people remember him? Curator: Precisely! And what does the presence of both sail and steam vessels represent, in the light of how history treats such displays of power? It embodies France grappling with its imperial past as it is on the brink of industrial modernity. The ships speak to power, the body speaks to immortality; the combination creates an image of potency. This print, distributed widely, became a tool to solidify a specific image of Napoleon and France itself. Editor: That makes so much sense. I didn’t initially see it as such a carefully constructed political message. Curator: These historical prints acted as vital means of disseminating political ideologies. Close readings encourage us to delve beneath surface aesthetics, asking 'who benefits' from an artwork's message? Editor: Definitely a fresh angle that changed my understanding of the image. It shows you can’t really separate art from its social context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.