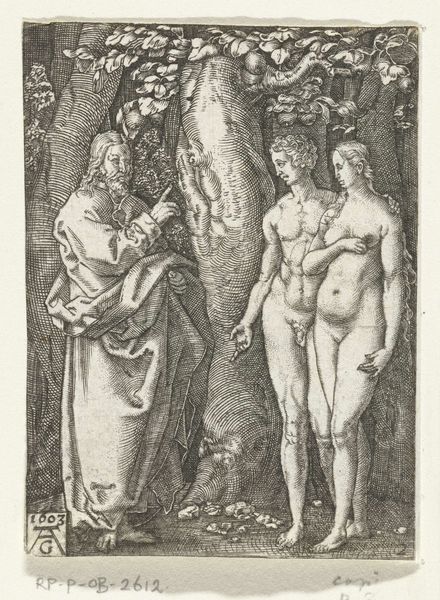

intaglio, woodcut, engraving

#

pen drawing

#

intaglio

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 61 mm, width 42 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intaglio print, simply called "The Ecstasy of Mary Magdalene," dates to around 1503. While the artist remains unknown, its home is here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The sharp contrast and the intense expressions of the figures give it an unsettling, almost claustrophobic feel, don’t you think? It’s fascinating and slightly disturbing all at once. Curator: Disturbing in what way? This work emerges during a period obsessed with female saints—especially those, like Mary Magdalene, who undergo dramatic transformations and public repentance. It catered to a very specific piety. Editor: Perhaps "unsettling" wasn’t the right word. Look at her body, idealized and nude, but also exposed, vulnerable, right? Placed among these adoring but slightly ambiguous figures – she lacks agency. Her experience, this ecstasy, seems dictated by outside forces. Curator: That interpretation definitely speaks to contemporary concerns. During the Northern Renaissance, such depictions sought to convey spiritual elevation through symbolic imagery. The act of being surrounded by angels signals her importance within the religious framework. Editor: But does it though? Or does it reflect a very gendered dynamic? I’m wondering what it meant to portray female religious ecstasy in such a visually vulnerable way, and the kind of messages about female bodies and spirituality it projected in its time. Is she truly elevated, or is this image simply reinforcing existing power dynamics by portraying the female experience in a highly sexualized way? Curator: We can't impose contemporary views onto 16th-century perceptions, entirely, of course. The artist likely intended a portrait of spiritual purification through divine encounter. It spoke to prevailing religious themes. The print's distribution through the church would bolster that narrative. Editor: Absolutely, but engaging with these artworks requires unpacking those complex layers. It's more than aesthetics or even theology; it's the cultural narrative that the image is upholding – often unconsciously – about gender and power, and in this instance female sexuality in a specific setting. Curator: It is that exact tension, I feel, between historical intent and contemporary critique that keeps these old artworks feeling perennially fresh. Editor: It certainly forces us to continually question the legacy and visual culture inherited across generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.