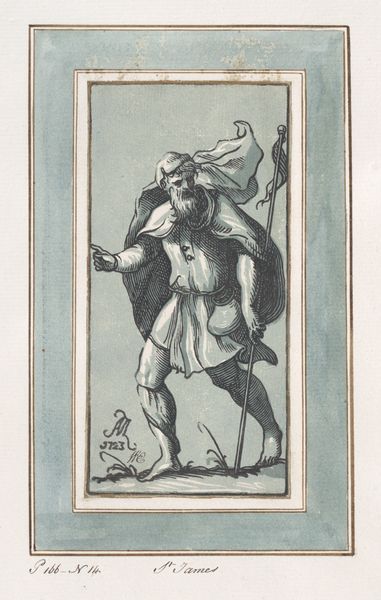

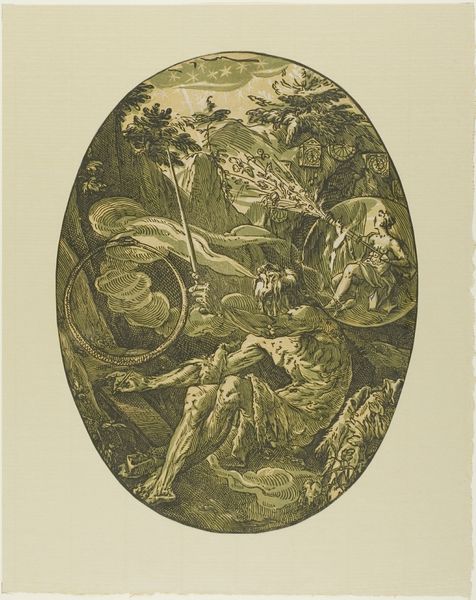

print, woodcut

#

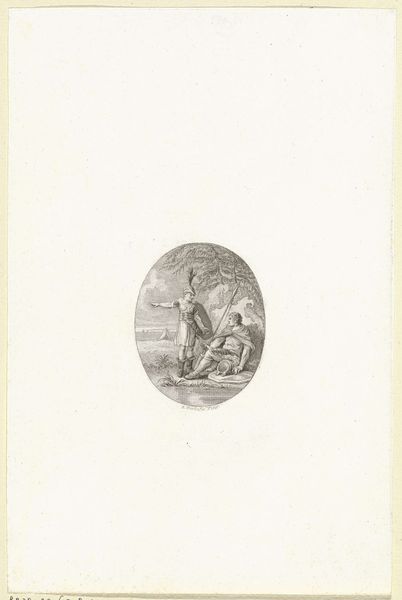

photo of handprinted image

#

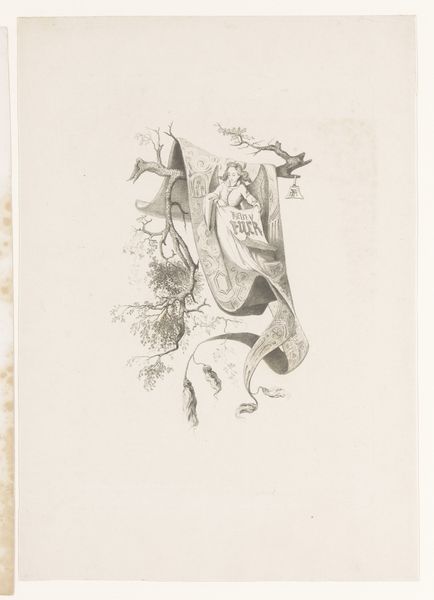

allegory

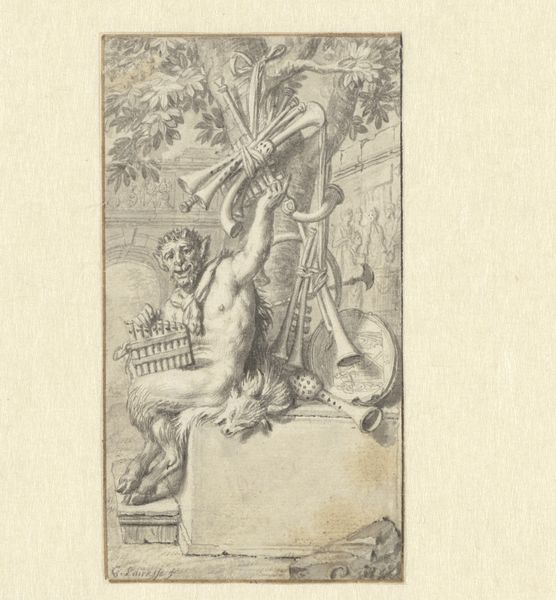

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ugo da Carpi created this intriguing woodcut, "Marsyas Finds Minerva's Flute," sometime between 1502 and 1532. The monochromatic print presents an oval framed scene. Editor: There's an almost dreamlike quality to this piece. The figures seem to emerge from the shaded background, and that cool, green hue lends an ethereal atmosphere. Curator: Absolutely. Da Carpi was a pioneer in the chiaroscuro woodcut technique, using multiple blocks to create tonal variations and dramatic contrasts. This print really highlights that method, achieving a remarkable depth. Editor: Seeing it now, the narrative has so many layers of possible readings. In what context would this have originally been viewed? How would a Renaissance audience interpret this imagery and its classical references? Curator: Consider that in the 16th century, printed images were a primary mode of disseminating classical stories and moral allegories to a wider audience. It's a complex power dynamic, where knowledge becomes both accessible and controlled. Da Carpi produced prints after designs by famous Renaissance painters, making high art attainable to collectors with diverse levels of income, but perhaps limiting true artistic interpretation and discussion by emphasizing the artists' established perspectives. Editor: Interesting point. Minerva's rejection of the flute resonates today; women being penalized, so to speak, for pursuing artistic or intellectual endeavors… And then Marsyas, later punished for his musical hubris. Curator: Yes, there are so many entry points for analyzing these symbolic narratives. How do cultural anxieties about skill, innovation, gender, and artistic license surface within this print and reflect societal attitudes of the Renaissance? Editor: Thanks, that background really enhances my understanding. I now see not just the aesthetics of a bygone era, but the social issues it's revealing. Curator: Indeed, by examining art through the lens of history, we can spark essential dialogues about social justice, now and then. Editor: I completely agree, these Renaissance artists still push boundaries when you consider who can benefit, interpret, and influence the dissemination of information across media.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.