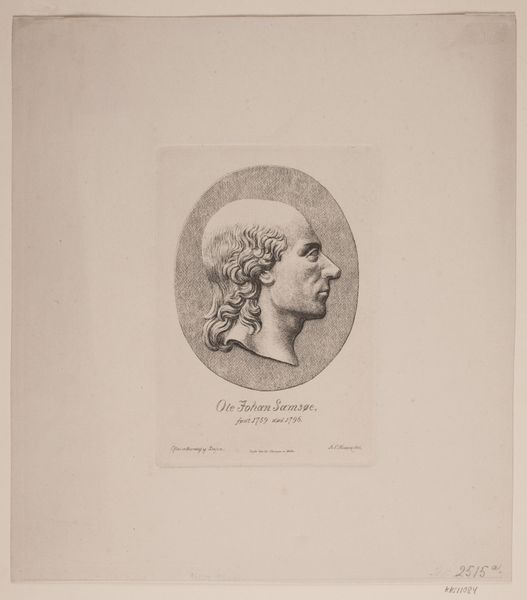

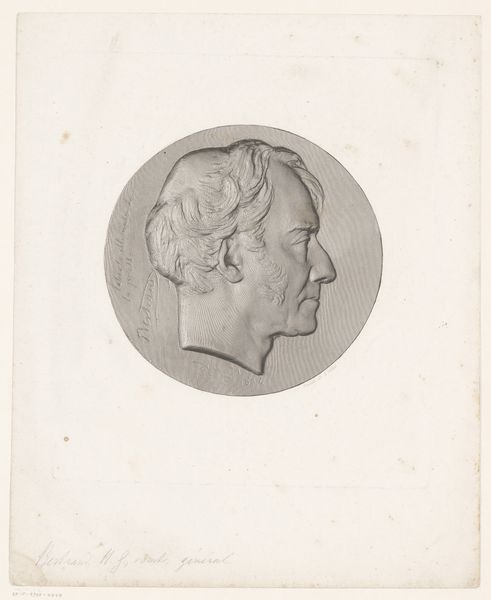

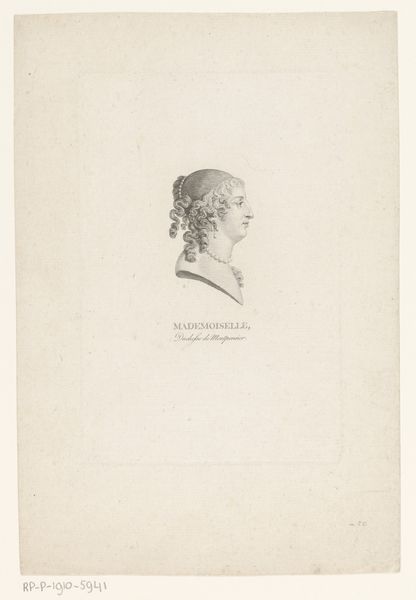

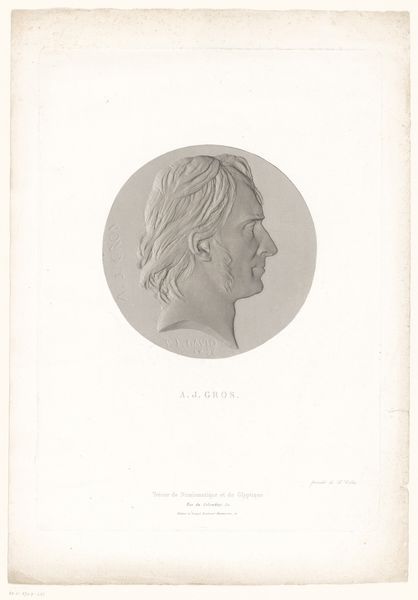

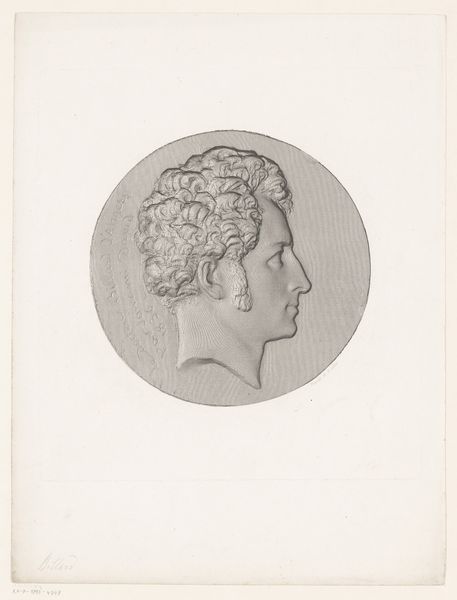

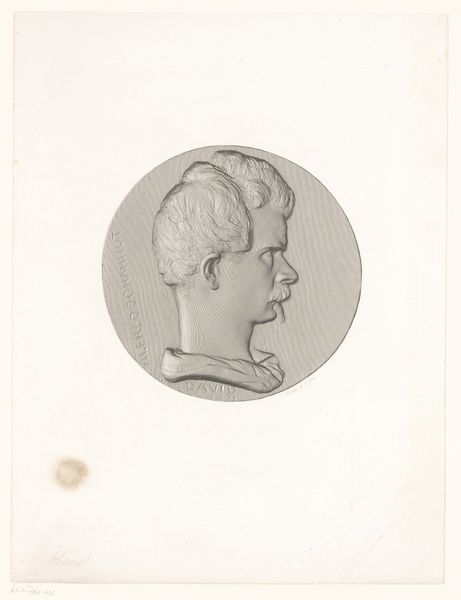

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

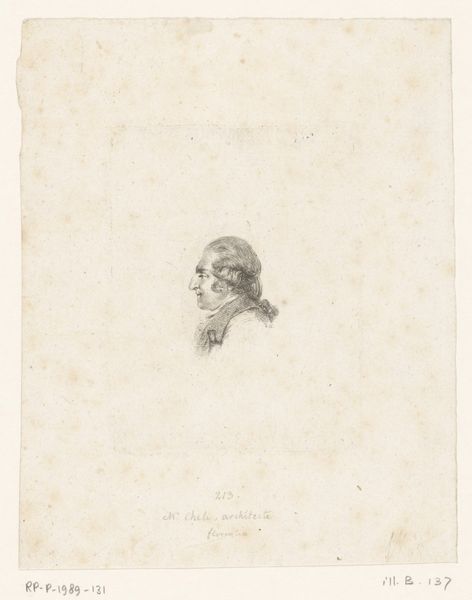

pencil drawn

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Carl Mayer’s "Portret van Wilhelm Waiblinger," dating between 1814 and 1868. It’s a print, an engraving. There's something quite stoic, even austere, about this profile. How do you interpret this work, particularly considering its historical context? Curator: That austerity speaks volumes, doesn't it? Let's consider the Romantic era in which this portrait emerged. This was a period grappling with social upheaval, the rise of individualism, and intense feelings. Portraits like these served to immortalize individuals but also to construct narratives around identity and belonging. How does Waiblinger's image engage with ideas of masculinity during this time? Is there a commentary on class, power, or perhaps even the artist's own position within this societal structure? Editor: I hadn't thought about masculinity so explicitly. His long hair and the slightly vulnerable expression complicate the typical "strong man" image that might be expected. Could this be a deliberate subversion? Curator: Precisely. The Romantics were not monolithic. They often challenged prevailing social norms through their art. We must ask: Whose gaze is privileged here? Who has the power to represent and who is being represented? Exploring those questions can help reveal deeper meanings embedded within what might initially appear as a simple portrait. Editor: It’s fascinating to consider how much is communicated beyond just a likeness. I will definitely think of that when I see similar pieces from the era. Curator: Indeed, this portrait becomes a site of negotiation – between artist and sitter, representation and reality, individual expression and collective identity. Every line tells a story, prompting us to interrogate the social fabric of the time and reflect on how we interpret similar images today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.