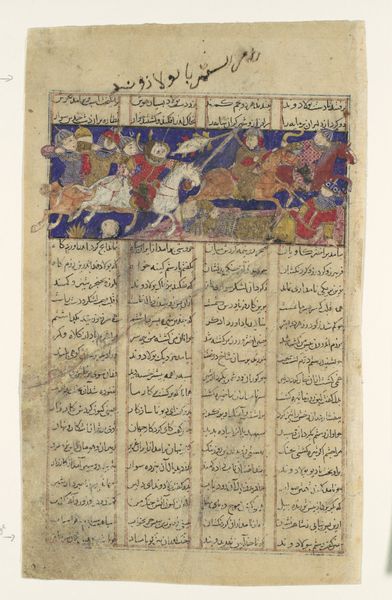

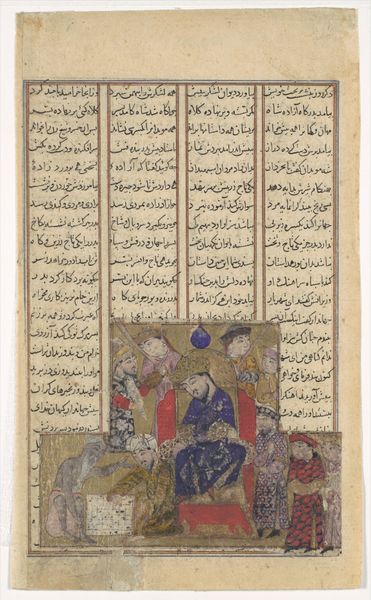

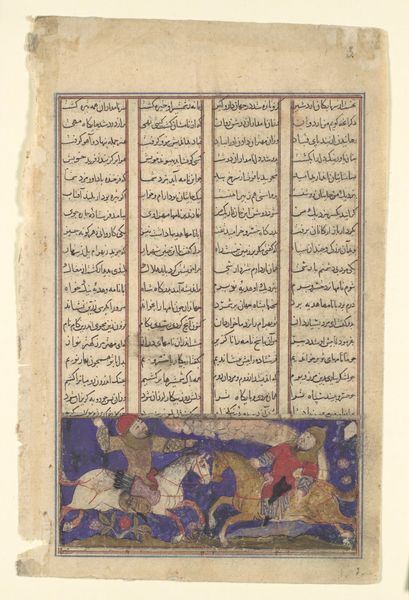

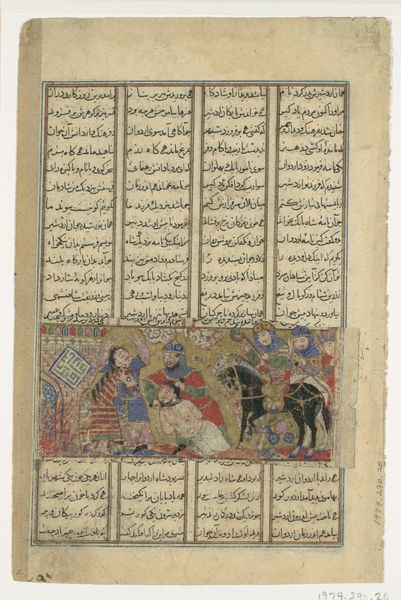

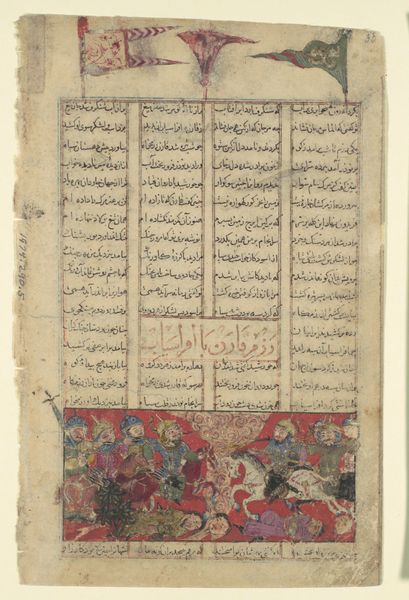

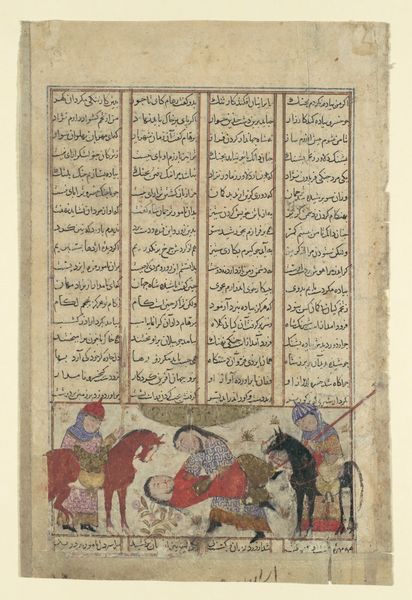

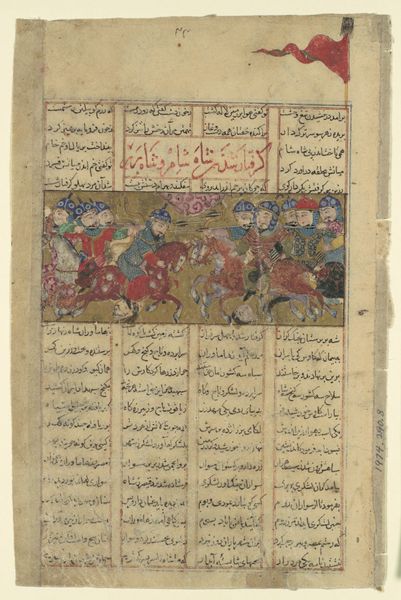

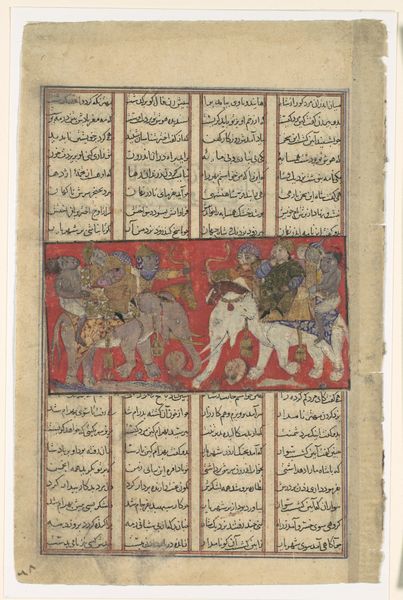

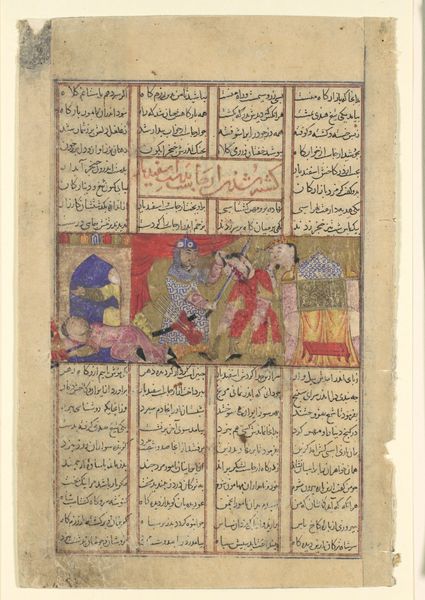

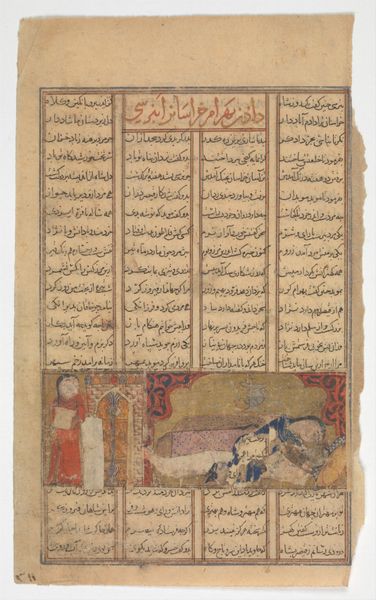

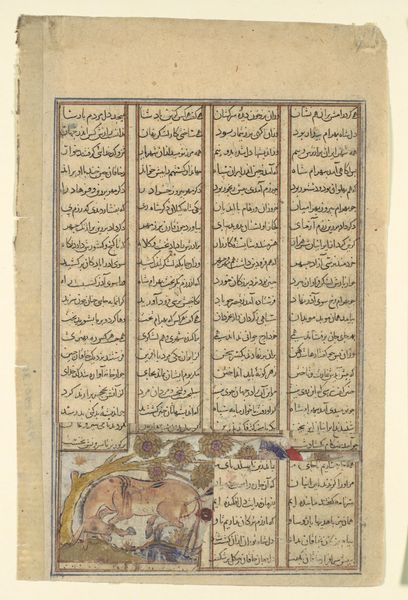

"The Combat of Rustam and Ashkabus", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings) 1305 - 1365

0:00

0:00

painting, watercolor

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

horse

#

men

#

islamic-art

#

miniature

Dimensions: Page: H. 8 in. (20.3 cm) W. 5 3/16 in. (13.2 cm) Painting: H. 1 11/16 in. (4.3 cm) W. 4 3/16 in. (10.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "The Combat of Rustam and Ashkabus," a painting on a folio from a Shahnama, or Book of Kings, made sometime between 1305 and 1365. It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The composition is striking – a vibrant scene of horses and warriors frozen mid-battle, all framed by lines of text. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see more than just a battle; I see a clash of ideologies, power dynamics expressed through the bodies and the text surrounding them. This miniature exists within a specific historical and political context, representing an era of cultural flourishing but also societal hierarchies. Notice how the artist positions Rustam, his dominance emphasized, potentially reinforcing a particular narrative about heroism and leadership prevalent during that time. Who is privileged in this telling and who is erased, and why? Editor: That's fascinating. I was focused on the action, but now I’m thinking about how the artist's choices reinforce social structures. The size and positioning of Rustam certainly commands attention. Curator: Exactly! Consider also the function of the *Shahnama* itself. It’s not just a collection of stories; it's a historical and cultural touchstone. How might illustrations like this contribute to shaping a collective Iranian identity, particularly in relation to its leadership and the construction of ideas around "heroism?” Do we view “The Book of Kings” as an activist, a preserver, a critical piece? Editor: I hadn't considered the idea of this work actively shaping identity. I am familiar with that happening in more contemporary artforms. Curator: Think about who had access to a lavishly illustrated manuscript like this? Patronage shaped not only the aesthetic qualities, but also its meaning. And who might have been excluded from this narrative? Considering these elements allows us to unearth some of its powerful social functions. Editor: That's a really powerful way of looking at it. It's made me think about how we engage with art from the past – not just as pretty pictures, but as active participants in a much bigger story. Curator: Precisely. Seeing art as a point of intersection for culture and philosophical values can give us great insight into why art continues to be one of our species’ longest running traditions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.