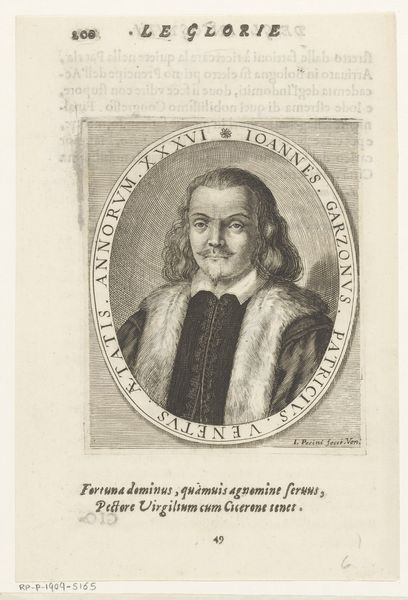

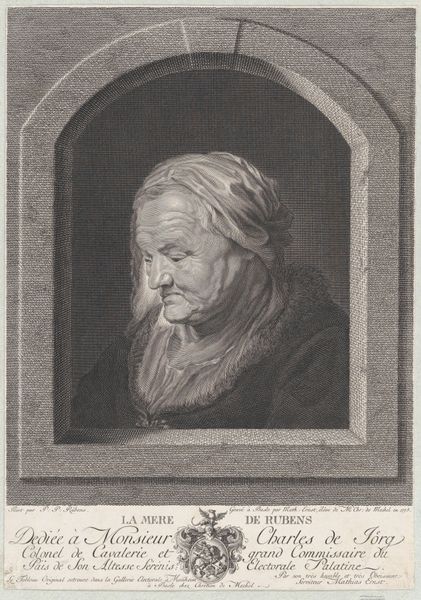

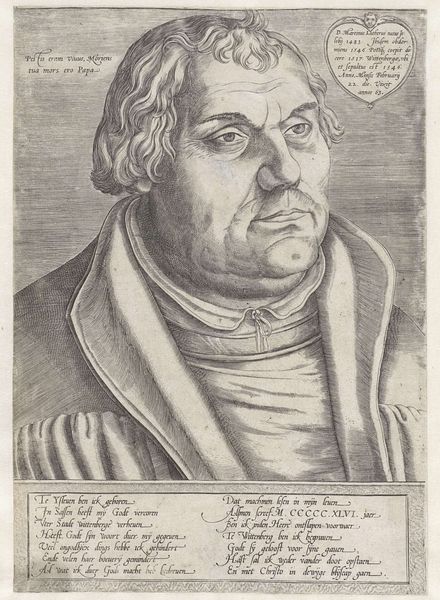

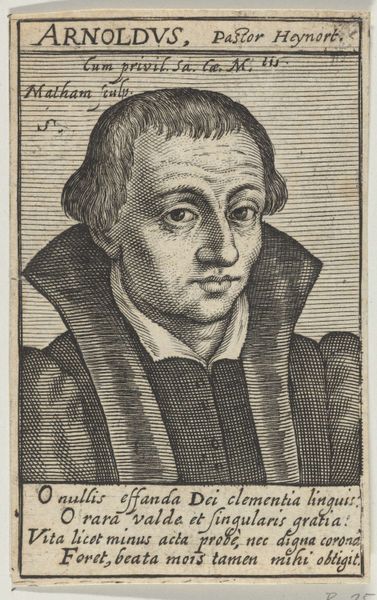

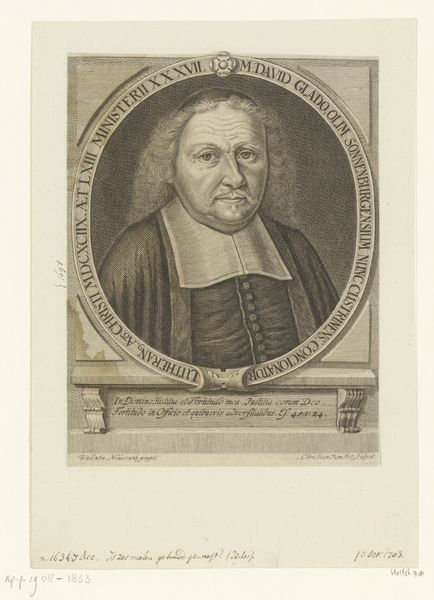

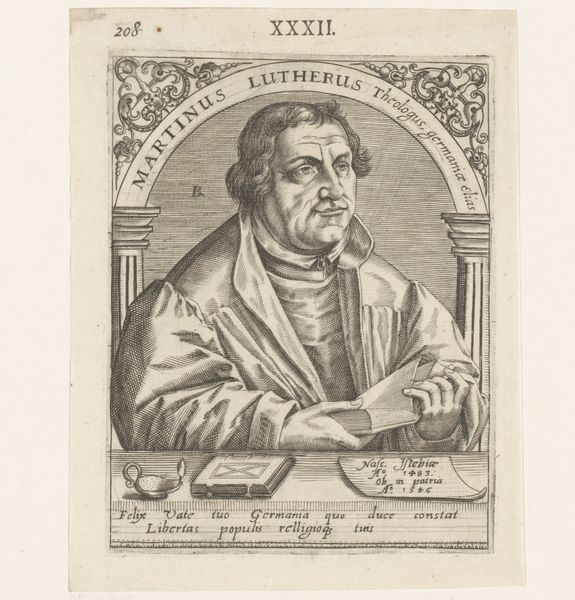

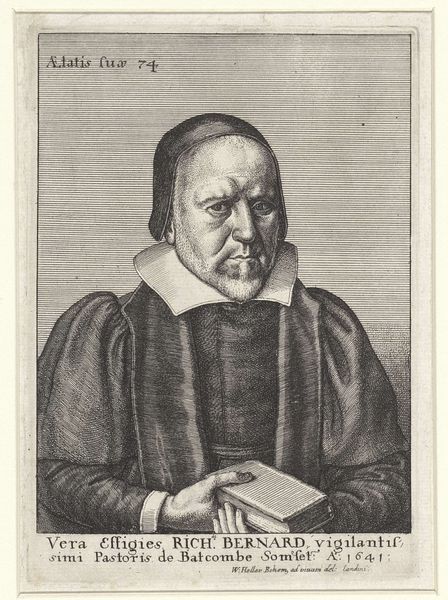

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 158 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The artwork before us, "Portret van Simone del Pollaiolo," attributed to Jean Baron and likely created between 1641 and 1741, offers a glimpse into a historical persona through the precise craft of engraving. Editor: My initial thought? This print evokes a peculiar blend of stoicism and vulnerability. There's something about the meticulous etching of his features that lays bare both his perceived dignity and a certain… human frailty. And what can you tell us about the context of portrait prints in this era? Curator: Prints such as this one, and engravings specifically, provided an essential function in disseminating images and solidifying legacies, particularly of architects or figures in history. Think about the labour involved in the original construction, its social function as part of state building. It allowed people without access to painted portraits to be recognized as important members of their world, to become "immortal". In a city like Florence, saturated with political maneuverings, visual representations cemented, and even challenged, power. The sitters costume could be considered, fur! In what context someone would have access to these clothes, what it means in terms of economy... Editor: Absolutely, let's not overlook the materiality inherent in the production itself. The copperplate engraving— the skill, the labor invested. Here is more than representation but a creation; not just of likeness, but also a tangible product of workshops and printmaking techniques. Consider how prints circulated widely compared to singular paintings; this brings forward the role of dissemination and affordability. By challenging traditional "high art", the value placed on the artist´s labour expands. The act of reproducing implies an acknowledgement of value that we as observers perpetuate. Curator: Right. Let's not underestimate the political narratives embedded within such "likenesses." Was the original artist or patron aiming to underscore certain political values? The stoicism we both see could signal civic virtue, or a desire for a narrative around an unwavering commitment to Florence, perhaps? Looking closely, there’s something unsettling about those eyes and their slightly different focal points—it feels less a faithful recreation and more a deliberate construction of character to fit within broader sociopolitical needs. Editor: A deliberate construction—yes. One also built upon materials, commerce, skilled labor, and reproductive technologies that granted these men longevity in a world ever craving visibility. Curator: An observation which encourages us to delve beyond just who Pollaiolo was and consider what role images played then, and what purpose their constant reiteration has now. Editor: Indeed, and further recognize all human implication from the artistic conception and production through our own gaze.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.