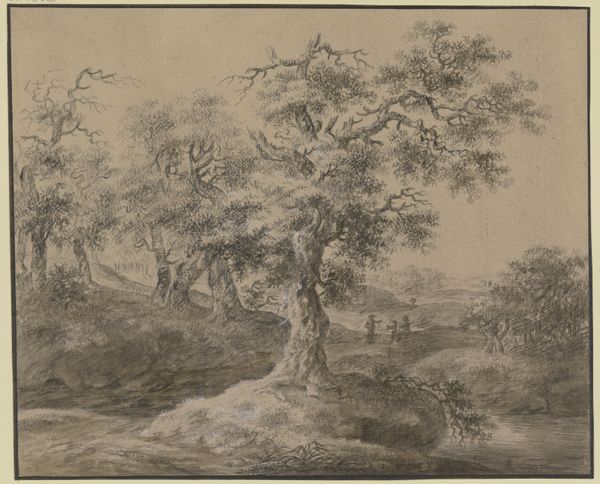

Lichtung im Eichenwald mit einer im Schatten rastenden Familie 1777

0:00

0:00

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s take a closer look at Bernard Gottfried Manskirsch's "Clearing in the Oak Forest with a Family Resting in the Shade," created in 1777. It's a delicate rendering, mostly graphite and pencil on paper, and it's housed right here at the Städel Museum. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the serenity of this piece. The light, airy composition evokes a sense of peacefulness. There's almost a timeless quality. Curator: It’s interesting that you use the word “timeless.” In the late 18th century, the rise of landscape art was very much intertwined with new ideas about nature and national identity. Artists weren’t just documenting a place; they were crafting emotional landscapes, projecting ideals of virtue and simplicity onto the natural world. Editor: Absolutely. Trees are very strong symbols – growth, endurance, wisdom, shelter. The figures taking refuge in its shade highlight this providing aspect; the familial ties enhance themes of nurturing, safety, continuity through generations, but perhaps, with those small, nearly indistinguishable people at the base of all those trees also feelings of transience. Curator: This work demonstrates some influences of Romanticism and a slight academic-art quality. Landscape as subject matter provided an acceptable visual code to convey ideas related to political and personal freedom. Images of people resting amidst grandiose landscapes celebrated ideas of individualism and personal identity while doing so in an environment, an idealized version of nature in this case, away from corrupting influences such as court society. Editor: Right, it taps into this universal longing for a return to simplicity, to an uncorrupted state. Curator: Considering the period, that idyllic imagery likely carried subversive undertones, particularly given some artistic censorship of the period across Europe. What appears tranquil might've subtly encouraged reflection on societal structures. Editor: It shows how nature provides comfort. I get a feeling of rest from overstimulation, perhaps a re-orientation of internal compass toward calm acceptance. The composition encourages introspection. It is quite easy to identify and project ourselves into one of the members of the family within that scene. Curator: Precisely. The piece encapsulates an important historical juncture: emerging aesthetic and philosophical movements intertwined with evolving socio-political contexts. Editor: It’s incredible how the simple medium of pencil on paper could speak so profoundly. Curator: Manskirsch used the available conventions to speak and convey through visual means very intricate political arguments during his time. Editor: Now, seeing it through this light helps me to look at it in new ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.