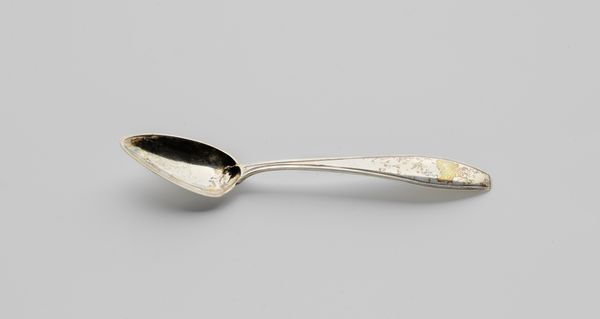

Dimensions: Length: 13 in. (33 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome to the gallery. We are looking at an exquisite silver ladle, dating back to 1796 or 1797. It's currently held here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Well, right off the bat, it's captivating! That gleaming surface, the way the light catches... and is it just me, or does that bowl evoke the feeling of a shell? It has such fluidity. Curator: The shell-like bowl is quintessential Rococo, a nod to nature, but cleverly elevated in precious silver. Silver's inherent properties also made it a perfect choice—malleable, and of course, resistant to corrosion. The touch of the artisan is palpable. We can ponder who crafted this. Was it an independent silversmith, or someone working for a larger manufactory? How might the societal status of that worker impact the item’s reception? Editor: The shell imagery resonates on multiple levels. It's Venus rising from the sea, but also speaks to journeys, souvenirs from afar… even luxury. Imagine the meals it graced, the rituals it participated in. It carries a potent message about status, doesn't it? Think of the contrast to utilitarian wooden spoons that would have been the everyday for common households at the time! Curator: Precisely. The very existence of such an object speaks volumes about societal structure. A ladle crafted from silver represents a concentration of wealth and resources dedicated not merely to eating, but to presenting the act of eating as performance. Let's also consider the circulation of silver, the labor involved in mining and processing the ore. Editor: Absolutely, but don't forget the psychological impact! Beyond just a display of wealth, there’s a subtle suggestion here: a delicate Rococo design reflecting a cultivated owner, someone deeply enmeshed in the currents of the era’s upper crust society. The shell also implies nourishment, a connection to primal marine sustenance. Curator: I appreciate you pointing out that inherent symbolism, even as I focus on how materials, labor, and context create deeper, sometimes overlooked readings of these pieces. We tend to glorify the craft without examining the conditions of its production and consumption. Editor: And that is the crucial point—material and context constantly inform each other. Looking deeper at both offers invaluable context. Thank you for illuminating that, truly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.