painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

high-renaissance

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

painted

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

mythology

#

italian-renaissance

#

portrait art

Copyright: Public domain

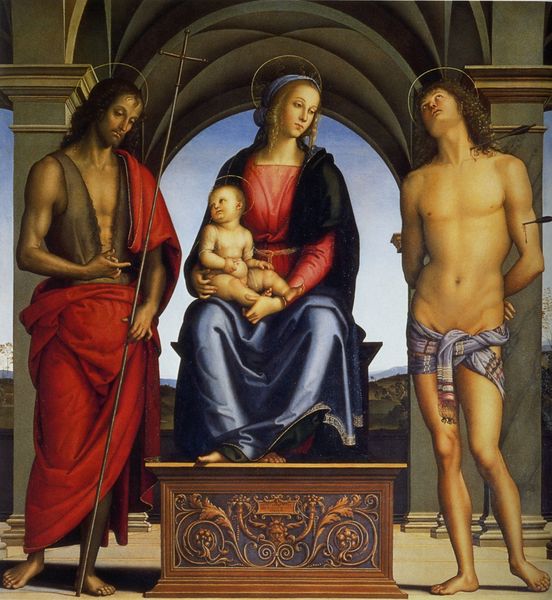

Curator: Good morning! We’re here in front of Andrea Mantegna’s "Madonna with St. Mary Magdalene and St. John the Baptist," painted around 1506. It's oil on wood, showcasing Mantegna’s signature style. What’s your initial take? Editor: Bleakly opulent, isn't it? The formality clashes with the somewhat unsettling intimacy of the figures. It feels staged, like a family portrait for gods. Curator: I think "staged" is spot-on. Mantegna loved to create these very constructed realities. You know, he had this amazing ability to combine classical forms with a palpable sense of the personal. Notice how each figure almost exists in their own world, despite the shared space. Editor: Absolutely. Mary Magdalene, for example, seems to be gazing somewhere beyond, almost like she envisions a world where women are treated as human beings, not defined by patriarchal constraints, eh? Her gaze reflects resistance. Curator: I love that. I always saw her pose as contemplative, but resistance is so much richer. And John the Baptist looks almost burdened, holding that scroll… Editor: Yes! It reminds us of the weight of prophecy, the expectations, the impossibility of living up to revolutionary ideals within oppressive systems. Is his nudity also hinting a departure of earthly constraints, perhaps? Curator: Perhaps. What I always get lost in, though, is Mary. The sorrow, the love, it all swirls together... Editor: Madonna, in all senses, symbolizes strength forged in vulnerability. However, while Renaissance idealized women to embody the burden of sorrow and sacrifice, they are, too, a representation of female oppression in Christianized traditions. Her story demands liberation. Curator: Absolutely! She has been, in all its complexity, an inspiration. She still is. And it makes me wonder how Mantegna thought of her when rendering these brushstrokes on this painting. Editor: Precisely. In this dialogue we reflect both on artistic expressions and social responsibilities that we take on interpreting historical images in our contemporary moment. Curator: So true. A perfect painting, alive for centuries, keeps pushing our vision of how to relate the past to a present always in need to be made fairer. Thanks! Editor: Thank you. It's a critical engagement to understand this portrayal as an object, also as a visual narrative that holds implications to our collective understanding of identity and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.