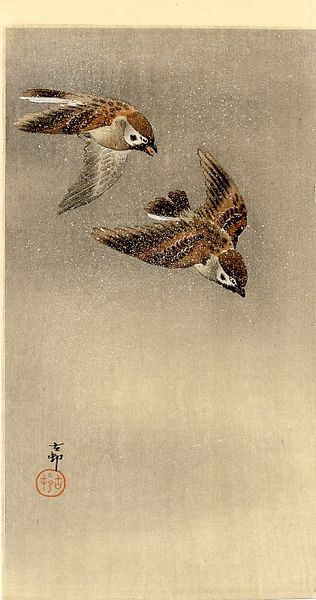

Dimensions: 35.5 x 19 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Before us is "Pheasant in Flight," a woodblock print created around 1910 by Ohara Koson. It's an elegant depiction of nature rendered through the techniques of the Ukiyo-e tradition. What strikes you initially? Editor: Immediately, the grayness captivates me; the gradient-like tonality seems to mute even the natural expressivity of the bird. One almost feels like it is trapped within its own historical moment. Curator: Precisely, the composition focuses the gaze—the eye travels immediately to the textured details of the wings in contrast with the darker head. The lines and textures of the feathers display a strong command of the woodblock medium. Note how his body almost merges into the misty background. Editor: Which reads perhaps, like the social conditions pressing against certain populations that would like to rise beyond their confines? The very form of Ukiyo-e developed within the urban centers but came to represent the margins...sex workers, outsiders, kabuki stars. Curator: An intriguing interpretation. But let us observe the print's structural components too. The positioning of the bird, the dynamism implied by the wings, creates a tension between movement and stillness—a sophisticated formal arrangement. Editor: And isn't it in this tension where the piece finds its strength? The composition mirrors societal dualities and reflects Japonisme—a broader cultural movement involving art, performance, literature, and even fashion... Did Koson find similar refuge within Japonisme itself? Curator: Koson found a new audience. Prints like these gained immense popularity in the West, contributing significantly to Japonisme. The detail would certainly appeal to European art buyers and connoisseurs interested in the natural world as an artistic motif. Editor: Which brings the history of ownership to light: Was this purchased for aesthetic appreciation alone? Is there an absence within our record, when these art objects move through colonialism to collection and gallery? The woodblock then acts not just as a landscape but an encoded document—a commentary on a shifting world. Curator: Yes, indeed; observing these artistic details in their historical context enhances and deepens one's interpretation, as does the artist’s manipulation of form. Editor: The very gray tonality could be indicative of societal pressures... it is an invitation to broaden discourse on cultural value as seen through its artistic and philosophical tradition. Curator: A valuable intersection of the work's aesthetic and political significance that we might both hold together as we leave.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.