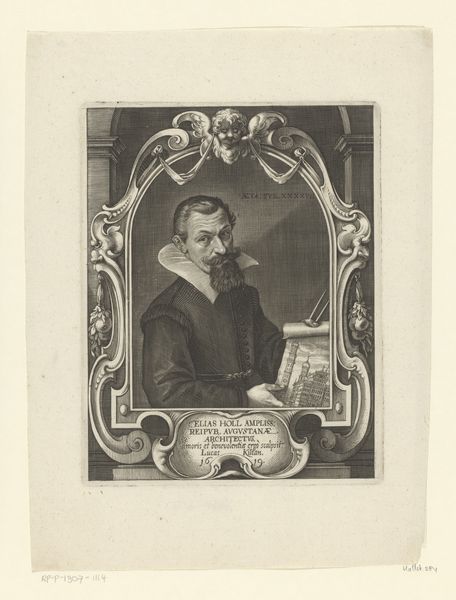

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 319 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving from 1644 by Grégoire Huret, titled "Portret van Arrigo Caterino Davila", strikes me as a fairly standard portrait for its time. Editor: Standard, yes, but something about the sitter’s gaze and the presence of that imposing suit of armour gives it a rather serious, almost unsettling tone. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, let’s think about it. We see Davila, likely portrayed after his death given the date, with symbols of his life as both a military figure and a historian. What does it mean to commemorate someone in this way? And more broadly, what purpose did portraits serve in the 17th century, beyond mere representation? Editor: It's about immortalizing them, crafting a narrative around their identity for future generations to look upon and understand them. Is it also a means of control of this person’s legacy? Curator: Precisely! Who gets remembered, and how they’re remembered, is always a political question. Consider Davila’s own historical writing – a history of the French civil wars. He shaped his own narrative and this portrait continues that process, creating a very specific impression. We have to consider the legacy carefully, not just at face value, but as part of a conscious effort to construct an image of power and legitimacy. And that armor certainly adds to the air of authority. Editor: So, it's less about objective truth and more about carefully constructing a legacy through visual means, cementing his place in history according to a very specific agenda? Curator: Exactly. Looking at it that way, how does this inform our view of the relationship between history, identity, and art? Editor: It really makes you think about how constructed all these seemingly straightforward historical images are.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.