Dimensions: height 344 mm, width 430 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

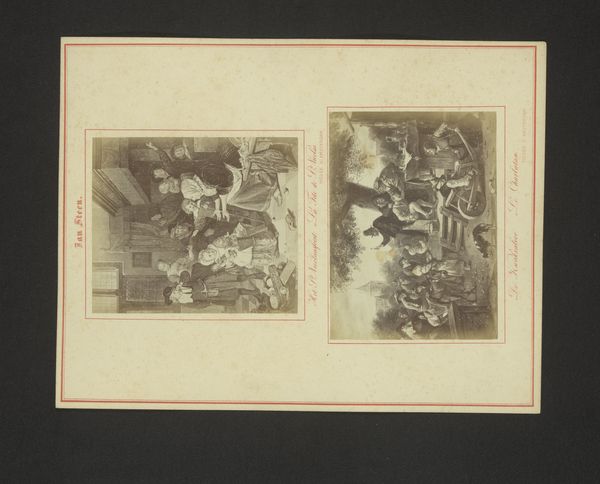

Curator: This piece, dating from the period 1869 to 1882, is called "Kindertaferelen," attributed to Gerhardus Philippus Zalsman, and appears to be a series of small scenes perhaps meant for children, executed as a woodcut or print. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by how quaint these vignettes feel. It’s the limited color palette, the rigid compositions—almost like an instructional diagram but softened by these childish scenes. There’s an appealing folk quality, almost naiveté, to the overall effect. Curator: The image contains visual echoes of Victorian storytelling. We see archetypal characters, and these echoes activate a memory, and connect to this period of didactic instruction, where symbolism was potent. A basket, a path, even the placement of figures signifies moral direction and journey. The intent seems both to amuse and to subtly instruct on values of this era. Editor: That the image comes to us via woodcut or some other type of print speaks volumes to its original function, no? Something relatively inexpensive, and thus widely available. It's a reproduction, not a precious original. Meant for consumption, handled roughly, part of the ephemera of childhood. The physical fact of the reproduction determines so much about the status, reception, and indeed the very being of the art, itself. Curator: A wonderful perspective; yes, prints, unlike unique paintings, find themselves directly interwoven with the material lives and habits of people. Consider the images, also. Comic strips are hinted at as there is textual explanation beneath each of them: these words interact with visual space to create an engaging story! It creates a different form of memory and impression, inviting discussion. Editor: I wonder about the labor, then. We rarely think of such things in relation to "high art" in painting and sculpture, and especially at this time when "fine art" became increasingly concerned with personal and authorial genius and so forth. But the "low art" of these prints speaks of division of labor and all the complications and, perhaps, solidarities implied by the materials. Curator: Such reflection highlights how materials ground experience. Understanding this print through the lens of its social circulation expands our reading of symbolic Victorian childhood as both charming innocence, and as commodified ideology. Editor: Yes, examining the means and ends of its making enriches, and complicates, its legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.