Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

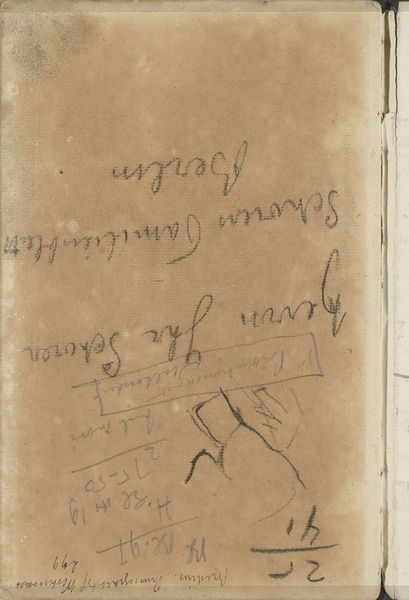

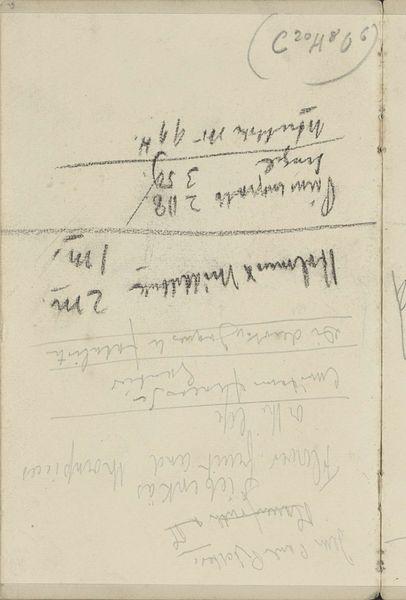

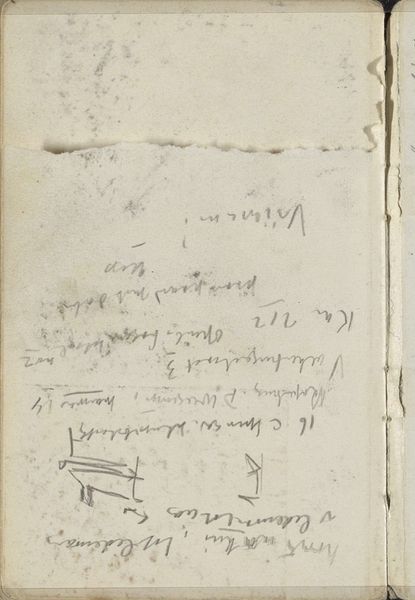

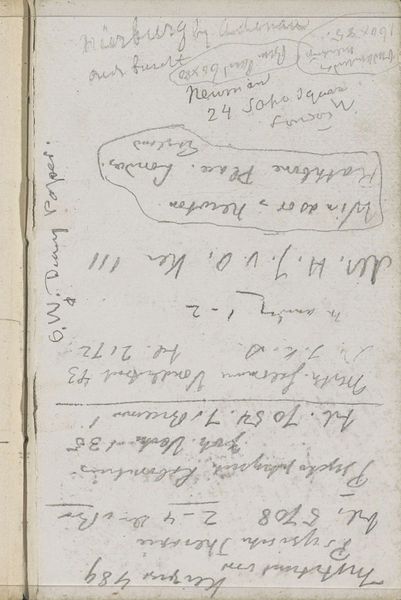

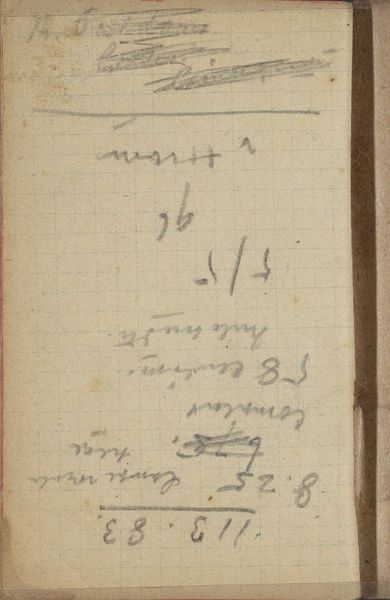

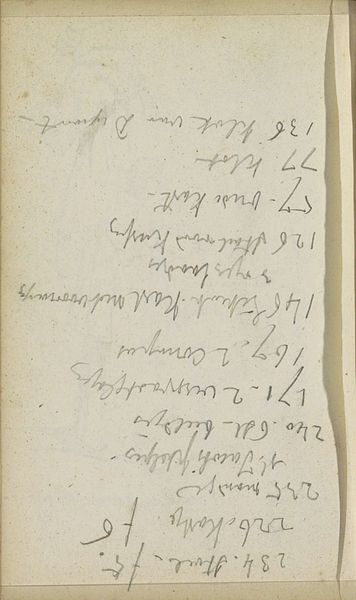

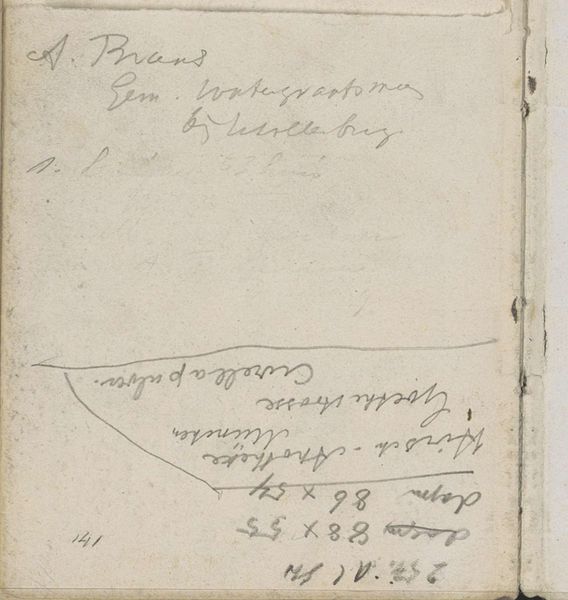

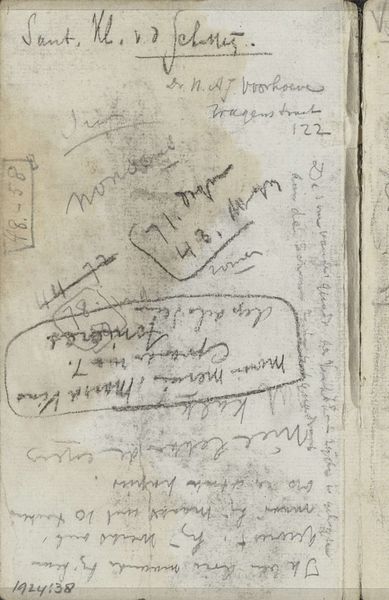

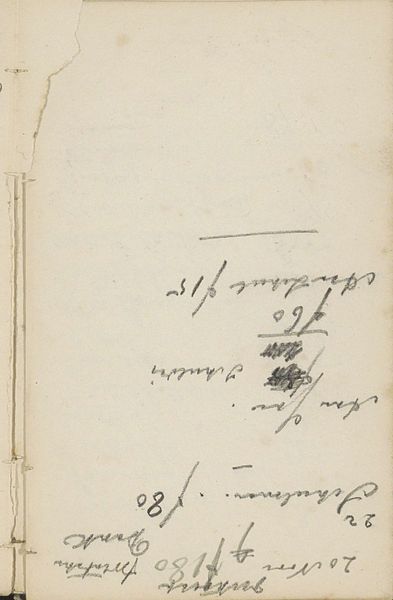

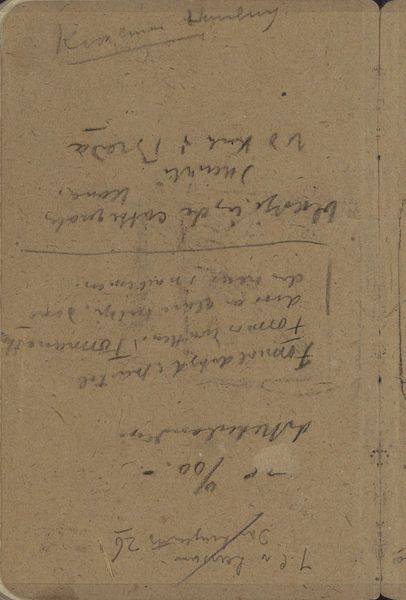

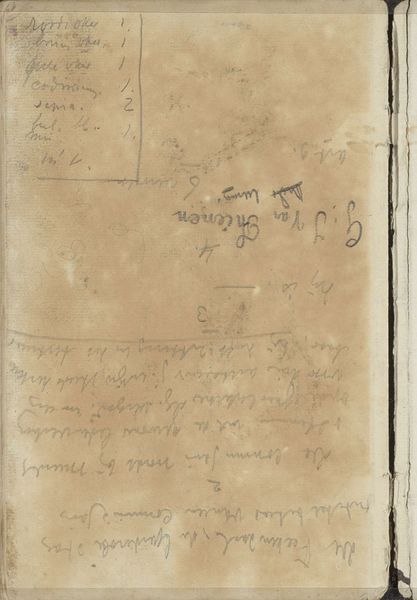

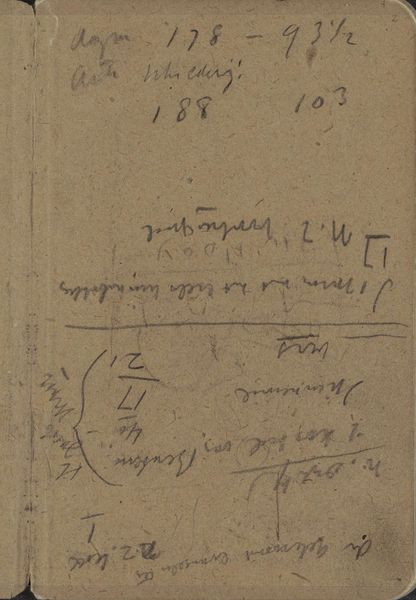

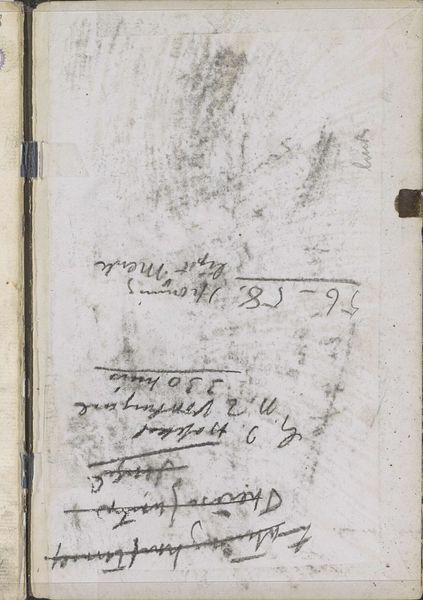

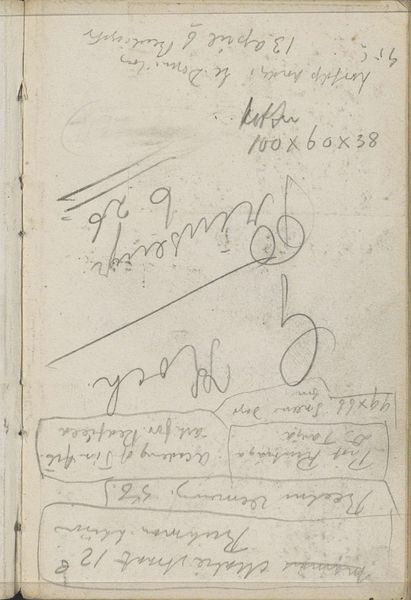

Curator: Here we have “Annotaties,” a sketchbook page created by George Hendrik Breitner between 1886 and 1898. It’s an ink drawing on paper, and currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by its intimacy. The hurried, almost frantic handwriting and faded ink create a strong sense of immediacy. It feels like we’re looking directly into Breitner’s personal thoughts, unfiltered. Curator: Yes, and what’s so fascinating is that it appears to be a mix of addresses, numerical calculations, and names. Breitner wasn’t necessarily creating art for public consumption here; this was for himself. In a way, it humanizes him beyond his celebrated cityscapes and portraits. Editor: Exactly. These "annotations" give us a glimpse of his world beyond the studio. The aged paper and hand-lettering are evidence of art's interaction with broader social themes of information management and communication—pre-internet, naturally! I’m curious about the choices behind using ink. How was its presence culturally perceived during Breitner's era? Curator: Ink, in those days, wasn't just a writing tool. It represented permanence and the seriousness of recorded thoughts. But, equally important, as we can see on this sketch, ink bleeds, it fades. And in its fading, in this example, it almost softens into nothing, inviting the next idea to float and find shape on the very same paper. Editor: This piece encourages us to reflect on how such ephemeral materials—sketchbooks, handwritten notes—preserve histories and ideas, particularly challenging given increased reliance on digital documentation that threatens long-term data preservation, raising questions about access and preservation within increasingly digitized societal narratives. What are the cultural ramifications if what counts as knowledge evolves toward more exclusionary platforms and tools? Curator: I see what you mean... On the one hand, the move to all things digital offers the potential for increased preservation. On the other hand, there's something beautiful, precious, and tactile about ink, paper, and the handwriting of a soul long since passed. We could reflect on the role of our senses, the haptic quality of knowing as we trace our hand along old texts. Editor: Ultimately, works like this one—where so much is obscured, but which, itself, does its very best to persist as object and trace of Breitner's life—allow viewers to confront some of our own beliefs around legacy and how, maybe, even through mere intention and material evidence we can achieve what we crave for future generations. Curator: That's wonderfully said. “Annotaties” invites a lingering meditation not just on the artist, but our collective, persistent and increasingly tenuous relation to the archive itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.