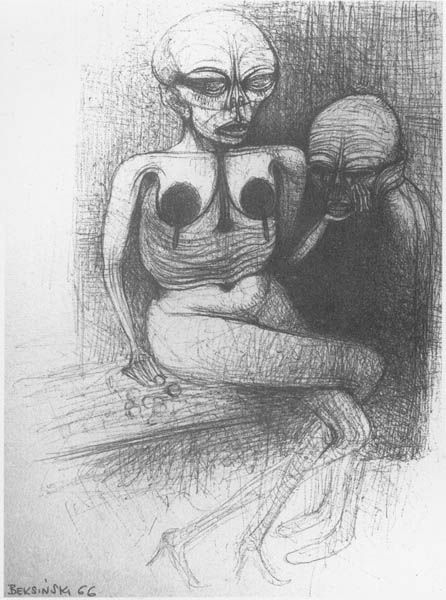

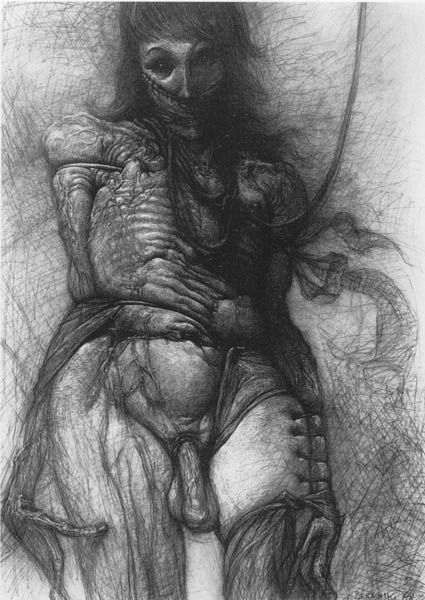

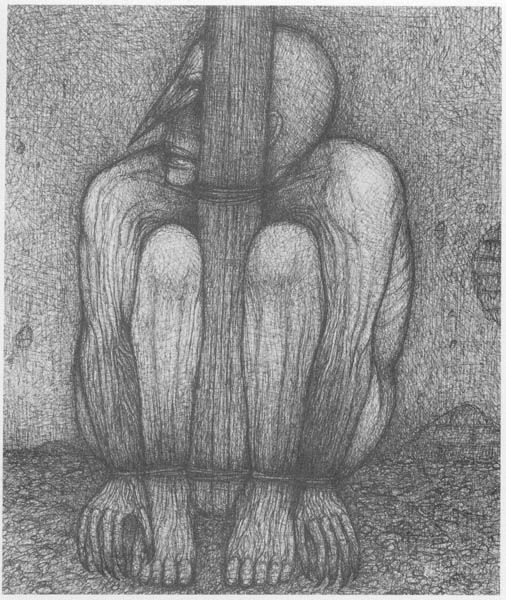

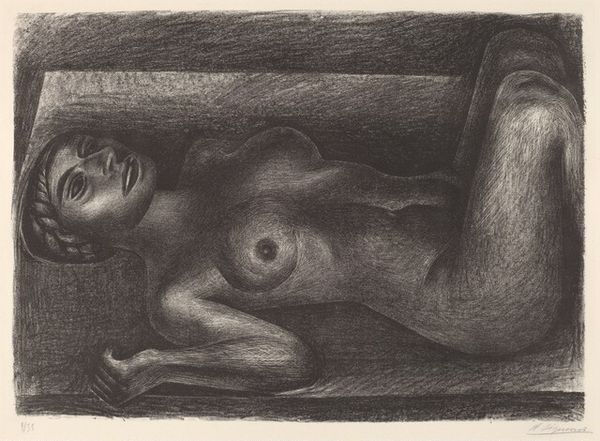

drawing, charcoal

#

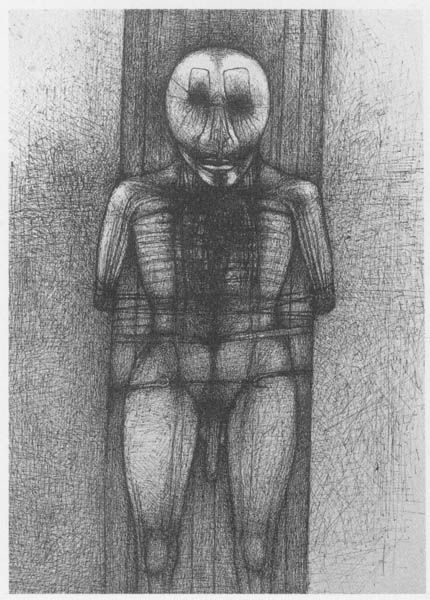

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

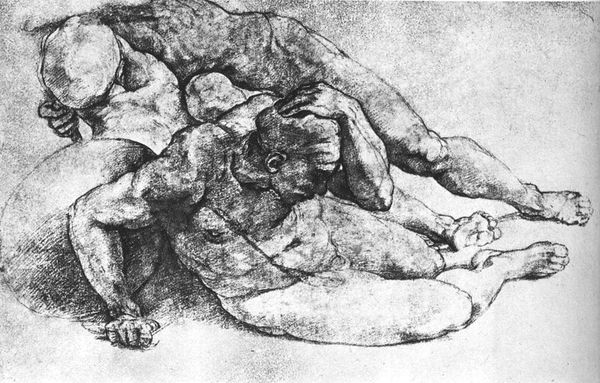

cubism

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

female-nude

#

pencil drawing

#

sketch

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

nude

#

modernism

Copyright: Pablo Picasso,Fair Use

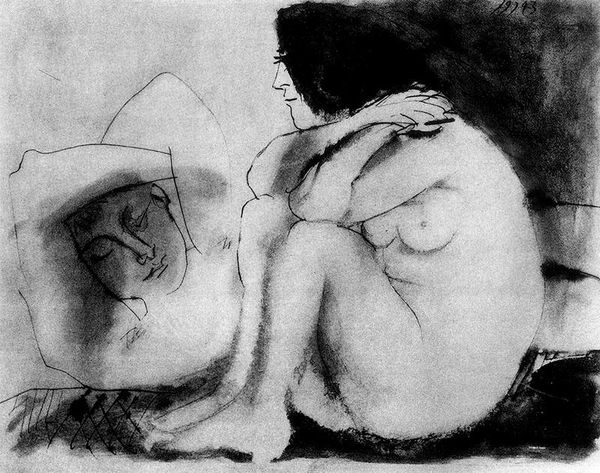

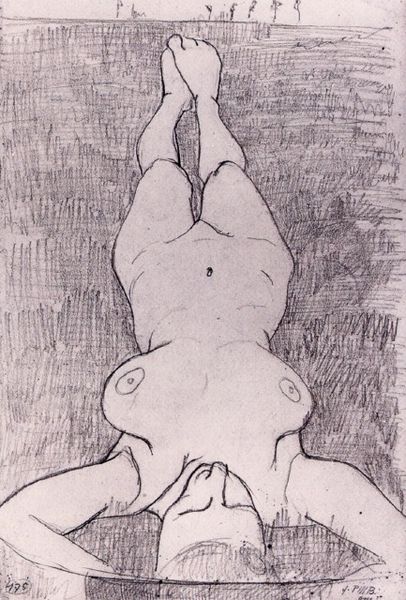

Curator: This unsettling sketch, "Woman washing her feet", comes to us from Pablo Picasso and was created in 1944. We see a charcoal and pencil drawing rendered in his distinctive Cubist style. What strikes you initially about this composition? Editor: It feels brutal, almost violent. The stark black and white, the distorted anatomy, the contorted pose… It speaks to a deep sense of unease. The intimacy of the act is violated by the aggressive lines. Curator: Indeed. Looking at the historical context, it is worth noting that Picasso created this during the Nazi occupation of Paris. This was a fraught time for artists who didn’t adhere to Nazi ideology, and art became a battleground for cultural resistance. Editor: That makes sense. The dehumanization inherent in fascist regimes certainly echoes in the disfigurement of the figure. Is she a victim? Or is there resilience here? I'm particularly drawn to the way the rough shading adds depth, but also a sense of confinement. She’s boxed in. Curator: One might argue that the domestic scene is infused with a subversive charge precisely because of its apparent banality. Public art was highly regulated; turning inwards to the private sphere could be a way of encoding resistance. Consider, also, Picasso’s evolving political stance and his complex engagement with representation. Editor: Absolutely, and I appreciate how the work also invites questions about the male gaze. Picasso’s portrayals of women are often complex, to say the least, teetering between adoration and objectification. How much agency does she possess? Is she performing a ritual or simply subjected to the artist’s gaze? Curator: Those tensions are inherent to Picasso’s process. By fragmenting and reassembling the body, he compels viewers to confront the constructed nature of representation itself. It reflects both his era and his artistic intentions, even decades after his death. Editor: This work is a powerful reminder that even the simplest domestic scenes can carry complex layers of political, social, and personal meaning, all at once. Curator: Precisely. The piece challenges us to consider art’s ability to reflect and resist in periods of unrest and repression. It serves as an evocative artifact for the student of history to deconstruct further.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.