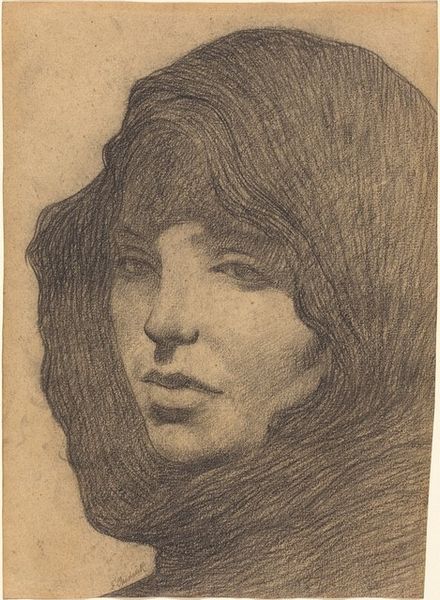

Dimensions: sheet: 61.28 × 48.26 cm (24 1/8 × 19 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

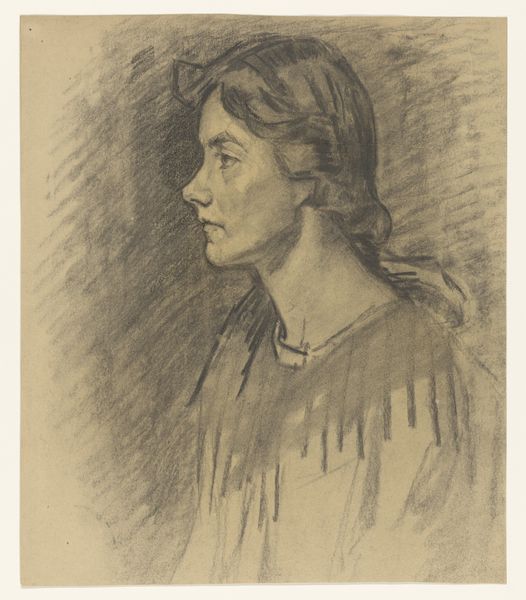

Editor: This is "A Woman," a charcoal drawing by Daniel Garber, probably created sometime in the early 1900s. There's a soft, almost hazy quality to the drawing. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: What strikes me is the explicit labor embedded in its production. The evident strokes, the smudging—all betray the physical act of making. Charcoal itself, a product of controlled burning, underscores a transformation of material. How do you think the use of charcoal contributes to our understanding of the sitter? Editor: Well, I think charcoal is a quick medium. You can create form with just the tone and shade, I feel. Is this academic art that prizes Realism? Curator: Precisely. Think about the broader context. Early 20th century; increasing industrialization. Artists are grappling with mass production, mechanization. Does Garber’s choice of a traditional medium like charcoal—over, say, photography, which was gaining popularity—make a statement about craft versus industry? Is it resistance, an embrace, or something in between? Editor: It could be a bit of both, I think. Maybe it's a way of clinging to the past while acknowledging the future. The very act of drawing emphasizes the artist's hand, a direct counterpoint to mechanical reproduction. Curator: Exactly. The work's value lies not only in the final image but in the embodied labor it represents. We should ask: who was producing charcoal, under what conditions? What were the social connotations of drawing as a skill? Editor: That’s an interesting point. Thinking about the supply chain, the economics of artmaking. Thank you. Curator: And thank you. It’s a reminder that even seemingly simple portrait drawings hold complex layers of meaning when we consider their material origins.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.