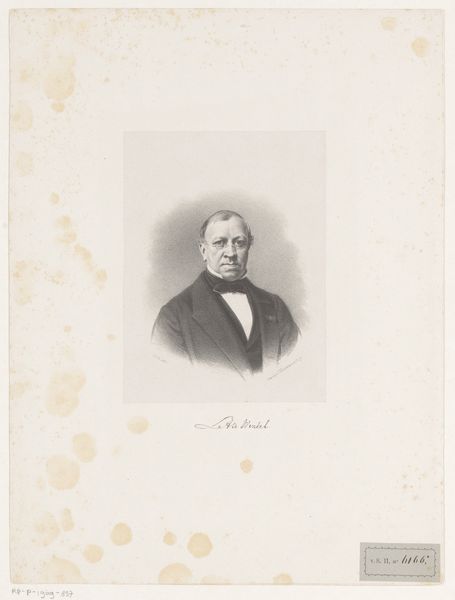

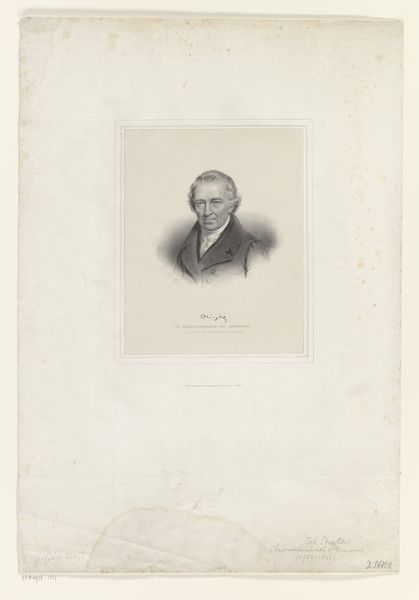

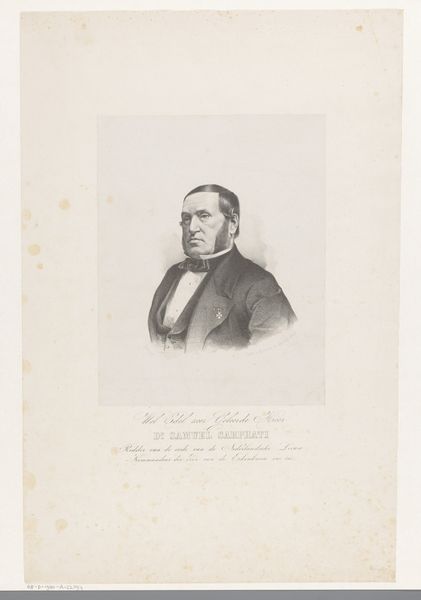

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

yellowing background

# print

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 512 mm, width 333 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Portret van Herman Antonie de Bloeme," an engraving dating from 1838 to 1863, attributed to Frederik Hendrik Weissenbruch. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum’s collection. The portrait depicts Herman Antonie de Bloeme, seemingly a man of importance at the time. Editor: It's striking how somber and almost severe he appears. There's a directness to his gaze, but the aged paper gives the image a faded, almost melancholy feel. What was the intended audience and purpose of such a portrait? Curator: In the 19th century, these kinds of portraits were often commissioned by or for civic organizations, academic institutions, or family collections. They served to commemorate and recognize the accomplishments of individuals within the community and underscore their status and legacy. Prints made portraiture more accessible, allowing for broader circulation beyond the elite circles typically commissioning painted portraits. Editor: Looking at the composition, I notice the subject’s severe hairstyle; how do you see these visual details fitting into the broader iconography of that era? Curator: A simple, practical, and, above all, serious visual register of a learned individual. Nothing here draws undue attention or diminishes a direct relationship to the man’s persona. The stark presentation amplifies a message of stability, intellect, and perhaps moral rectitude. Weissenbruch really captured what defined this period. Editor: You’re right; it's compelling how the engraver utilizes line and shadow to create not just a likeness, but also a sense of the individual's character or social standing. There’s a tangible weightiness to this image; the sitter looks rather unapproachable. Curator: Yes, in its time this engraving, beyond simply reproducing an individual’s likeness, conveyed the values society sought to uphold, using visual cues to construct the idea of an important figure. The role of art as social documentation is vividly present. Editor: Reflecting on it, I now see how that austere presentation wasn't just a choice but rather a strategic way to solidify perceptions of this individual's worth, cementing it for posterity through widespread visual culture. Curator: Indeed, by looking closely at such images, we can learn how society’s ideals were visualized and promoted.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.